75 Years Later: Digitally Commemorating the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen

75 Years Later: Digitally Commemorating the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen

This week – 15th April – was the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. Yet, unlike previous commemorations, the date was marked with online-only rather than physical events at the site.

A few years ago, when I was writing my last book Cinematic Intermedialities and Contemporary Holocaust Memory, I went on a research trip to the Gedenkstaette Bergen-Belsen to explore their Here: Space of Memory project, a collaboration with the SPECS Research Group in Barcelona. The audio-visual installation stood in a box at the Anne-Frank-Platz in the Memorial’s ground from October 28th 2012 until February 2014. A short trailer by SPECs shows the original installation here:

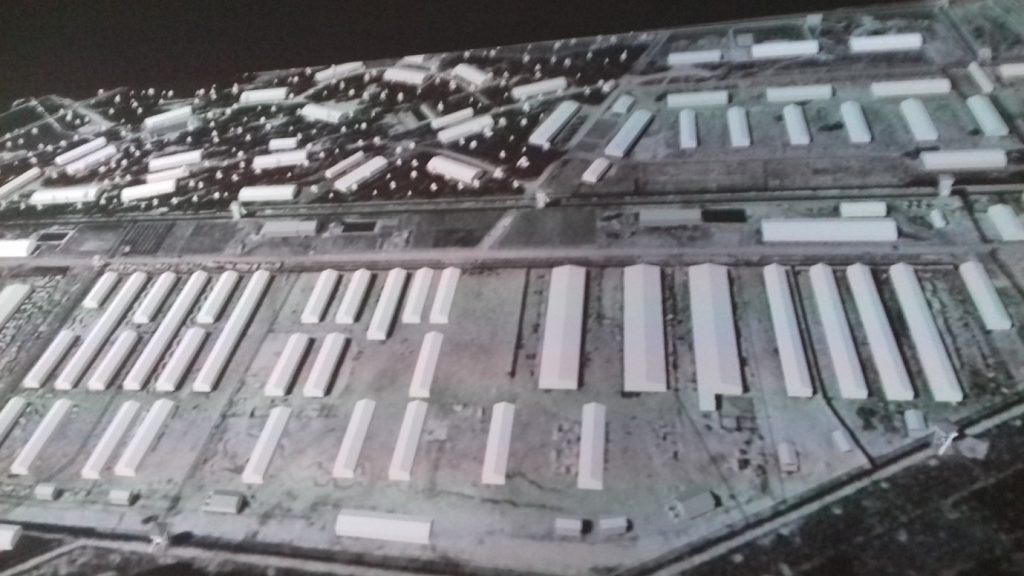

The installation’s content continues to exist in an augmented-reality (AR) app on i-pads, which visitors can hire at the site. AR technology blends virtual reality (VR) content with images of the lived-world environment. This is particularly effective at Bergen-Belsen because the typhoid outbreak in 1945 meant that the camp’s structures had to be destroyed. There are few physical remains of the site – unlike Auschwitz I and other well-visited concentration camp memorials.

Photograph of Victoria Grace-Walden engaging with the Here: Spaces of Memory Project on site. All photographs were taken by Imogen Dalziel

So, how does using the app affect one’s experience with the geographic place as it looks today? In Cinematic Intermedialities, I argue that Here: Space of Memory is a particularly powerful memorial project because it positions us in the space ‘inbetween a variety of entities, not only the mostly empty landscape of the present and the app’s maps’, but also fragments of diaries, photographs, letters and testimonies (2019, 208). There are two distinct features of the app worth exploring further in this short blog:

- The app presents a three-dimensional model of the camp’s historical structures over a view of the modern-day geographical space. However, the buildings are shown as grey blocks, trees are conical shapes on rectangular stalks and images of humans moving around the camp are absent. It looks more like a prototype model for a computer game than an historical representation. Such a representational – or perhaps non-representational – strategy prevents visitors leaving with a sense of ‘I was there’ – an imagined trip into the past, which many VR experiences claim to offer. Thus, the app keeps the visitor positioned between the past and the present. It encourages us to negotiate between the very temporal dimensions that characterise memory (the past and the present), and thus asks us to become actively involved and responsible in memory-creation.

Victoria Grace Walden engaging with the Here: Spaces of Memory Project on site

- The wide variety of voices we ‘hear’ through the app’s digital archive gives us glimpses of different people’s historical experiences (through photographs, diaries and testimonies etc.). We do not follow a single individual’s story as if it can stand in for the vast range of different experiences, instead we engage with only fragments – each encounter is fleeting. I have argued such brief engagement with each person keeps the visitor in a ‘liminal position recognising that they cannot understand these witnesses and victims’ lived experiences of this place [in full], yet, in spite of this, to repeat Didi-Huberman’s phrase, they can and are most likely compelled to remember’ (2019, 209). Didi-Huberman (2012) reminds us that we share both semblance and dissemblance with camp victims (and one could argue similarly for liberators and perpetrators). Semblance in that they are humans just like us, but dissemblance in that their experiences are nothing like those we have encountered. If we are to remember this past, which is not ours, but was a traumatic period for others, then it is important to recognise both our similarities and differences with the people to whom this past belongs.

Here: Spaces of Memory is a very powerful digital memorial because it activates visitors to become ethically responsible for continuing memory of this site. It achieves this by positioning us inbetween past and present, and semblance and dissemblance – in the very space from which collective memory can be created.

Below are a number of online sources with more information about the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and 2020 online-only commemorations:

- Befreiung1945 is the official online memorial of the Bergen-Belsen Memorial, in place of the 19th April 2020 commemorations that would have happened onsite. This comprehensive space has videos from speakers that would have contributed to this year’s event alongside a wealth of educational content.

- UCL and the Holocaust Educational Trust (HET) had launched a series of educational trips to the Memorial, whilst I know some of these did go ahead, I assume the project was cut short by the effects of Covid-19. Nevertheless, HET has published resources online. The activities encourage people to participate on social media, by sharing posters with survivors’ quotes with the hashtags #Belsen75, #ThisIsOurStory, and #HETAmbassadors.

- The United Kingdom Holocaust Memorial Foundation has launched a public appeal via www.big-ideas.org for people to paint ‘foundation stones’ for the planned Holocaust memorial site in London. One of the options, promoted on Twitter this week, is to paint a stone in commemoration of Bergen-Belsen.

- A trace of commemoration events that did not happen: The World Jewish Congress shares this itinerary for activities at the Bergen-Belsen Memorial.

- For more information about the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, the Imperial War Museum shares a series of audio clips of liberators and its Google Arts and Culture exhibit.

- You can also find our more via the USHMM’s Bergen-Belsen encylopedia series and

- The USC Shoah Foundation’s online exhibit ‘Stories of Liberation’, which includes survivor testimony.

Want to read more?

Debunking Digital Myths

Call for support creating a Covid-19 archive of digital resources

What’s in a name? Naming Holocaust research projects on social media