Anne Frank Virtual Tour of Bergen-Belsen

Anne Frank Virtual Tour of Bergen-Belsen

Friday the 12th of June marked the birthday of Anne Frank – perhaps the most famous victim of the Holocaust. To commemorate this date, staff at the memorial to Bergen-Belsen presented a live Instagram tour of the site focusing on Anne’s time at the concentration camp. In this week’s post, I offer a critical reflection of my experience on that ‘virtual tour’.

A Critical Walkthough

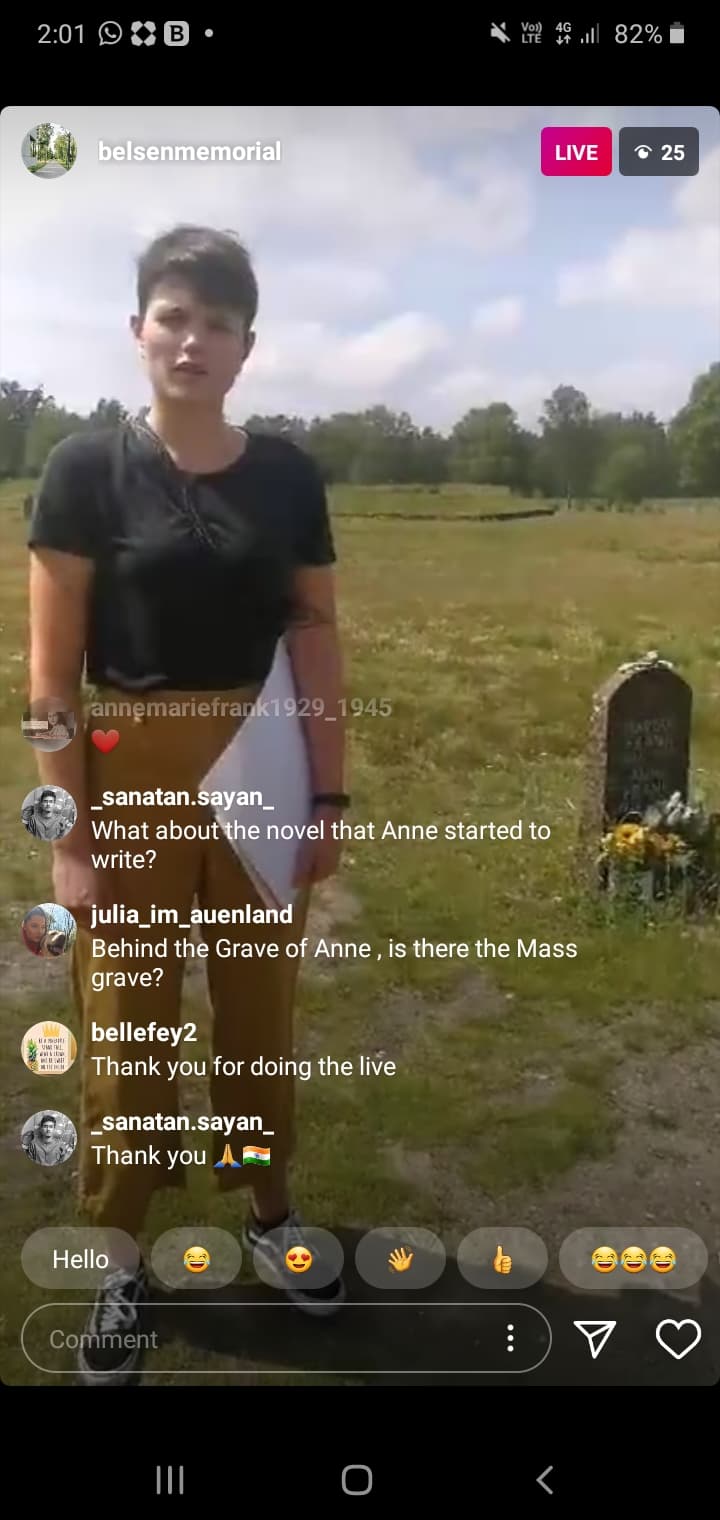

Sat at my desk at home, I pulled Instagram up on my phone and waited for the avatar of @belsenmemorial to flash that it was ‘live’. The video would offer a guided walk of areas of the site associated with Anne’s story.

It started, as many digital experiences do, by setting the rules for engagement. We were encouraged to ask questions via the comments function, and to ask them throughout the tour not just at the end.

I was struck by the number of coloured heart emojis clicked almost immediately and throughout the tour. Does there exist an appropriate repertoire of emojis for expressing one’s feelings whilst visiting a concentration camp?

Almost immediately, our distance from the physical site is highlighted as the guide notes she is bitten by an insect, an experience it is unlikely we are going to share on this tour.

Our guide orientates the distanced audience within the physical space of the site by displaying a lamanated map, much like guides do when visitors take guided tours at such sites, and points to where we are. This practice plays a particularly important role online when we are not in the site and our view of it is restricted by the frame of the mobile device filming the tour.

The camera operator serves as conduit between viewers and the guide as the latter asks:

‘are there comments?’

‘not yet’

‘I will continue then’.

As questions begin to appear, they are posed to the guide very quickly even if this interrupts the guide’s flow. This is reminiscient of the experience of in-person guided tours during which visitors rarely hesitate to wait before they speak.

The virtual tour encapsulates much of the performativity, interaction and liveness of a typical in-person group tour. It has the same ephemeral quality – a one off, collective experience. One might call this a remediation of a guided tour, if indeed we can think of guided tours as mediation themselves.

The two logics of remediation that Bolter and Grusin (2000) identify are certainly present. Immediacy, on the one hand, with the liveness and chatter that is foregrounded on the screen as user comments and the guide’s direct address to us. Yet, also hypermediacy on the other hand as the wind at times is caught by the recording device’s microphone so that the guide is difficult to hear. These moments draw attention to my physical distance from the site. Like the insects, biting the guide’s leg, the wind is a specific, natural quality of that space far away from my home office. I am aware I am watching through my device, emphasised further by the overlaying of other user’s comments which disrupt my view of the field.

The close framing of the tour, filmed on a mobile device, means our focus is mostly on the guide, although there are moments when the camera pans to show particular spaces such as the main ‘street’ of the camp.

The guide reminds us several times that ‘nothing is really visible’ anymore. Nevertheless, we still get a sense of the scale of Bergen-Belsen as we follow the guide walking, in real time, across the site. It is through her bodily movement that the geographical space can be felt by us. Spatiality translates into temporality. After a short walk, the guide reorientates us using the map.

I am particularly intrigued by the motivation of other viewers. One, @bellefrey2 asks almost immediately to see the ‘grave’ of Anne Frank now as they have to leave the live stream. Their first request does not recieve a response, but they quickly repeat it. The guide corrects them that it is not a ‘grave’ but rather a ‘memorial stone’ and it is very far away from her current position and therefore the tour will not go there until later. However, the video is being recorded, so they can view it later if they wish. @bellefrey2 does not push this further, they seem satisfied merely that their request was acknowledge and they actually stay right until the end saying ‘thank you’ at the moment the memorial stone is revealed.

This interaction emphasises a desire ‘to see’, to witness and to get a sense of being-there-ness and materiality, all qualities essential to current paradigms of doing Holocaust memory and commemoration. Yet, this is also combined with a desire for agency and an individualised experience, factors that are characteristic of Web 2.0 experiences. @bellefrey2’s engagement with the tour draws attention to the points of tension between traditional, institutionalised memory practices and user expectations of contemporary, hyperconnective online spaces.

In the final moments of the tour, as the guide is coming to conclusions at the memorial stone, one astute viewer notices something in the background and asks if that is one of the mass graves. The guide and camera operator take this question as a request to see and go over to one of these mounds to confirm that it is.

This brief 30-minutes tour is a micro-tour which seems to acknowledge the web as a space of new micro-temporalities, not only at the levels of protocols and processing as Wolfgang Ernst (2013) has argued, but increasingly in our uses of it as we prefer micro-blogging to long reads (like this!) and immediacy over waiting. An in-person visit to the memorial at Bergen-Belsen can take an entire day of one’s time and it is not easy to get to by public transport. We are reminded at the end of this micro-tour though that we have not seen everything – that we do not now know everything, but we can join another 30 minute experience focusing on prisoners of war narratives related to the site in a few weeks.

Digital Reproduction

Virtual tours like this offer remediated versions of in-person tours, they are not essentially digital, but they are particularly welcomed at a time when many of us cannot visit memory sites. Bolter and Grusin define remediation as relying on two logics: immediacy and hypermediacy – we simultaneously feel a sense of presence and yet mediated distance (we are hyper aware of the interface). The embodiment of the guide, whose movements we follow and the liveness of the tour gives us the sense of immediacy, yet the overwriting of comments and heart emojis on the image remind us constantly of our distance from the lived-world space of the memorial and the interface with which we can interact, yet we are also aware of the communal ‘live’ experience we are immediately taking part in.

Nevertheless, my experience on the tour, particularly observing the engagement of @bellefey2 makes me question ‘what might an essentially digital tour be like?’ How can commemoration sites create tours that foreground the call for agency and create individualised experiences like this viewer seemed to desire?

The Bergen-Belsen memorial already does this to some extent with their onsite i-Pad app, but could this be translated online and how could it incorporate more participatory elements that enable a democratisation of memory-production so that viewers truly become not only users but creators of memory?

Andrew Hoskins (2018) argues that with greater hyperconnectivity emerges ‘a new collective responsibility’. Whilst historical writing about media witnessing has often suggested a element of complicity on the part of the viewer for what they view, This new collective responsibility refers to constant calls to action. It is not enough to just see and thus be complicit, we must do. Although, this is often interpretated into clicktivism where a few clicks to different online spaces or comments satisifies our sense that we have played our part to know or react. What might such a hyperconnective, digital memory look like then that disperses responsibility for memory production across guides, curators, archivists, testimonies, sites, objects, computers, the Internet, protocols, algorithms, code and users, and other organic and nonorganic Beings?

Is it perhaps better to speak of this potential memory experience as hyperconnective Holocaust memory not simply digital Holocaust memory?

Digital after all really refers to discreteness in contrast to the continuity implied by analogue. In this sense, the Anne Frank micro-tour is essentially digital, but I wonder how much further we can go towards hyperconnective potentiality.

Read More

Digitally Commemorating the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen