Beyond the Single Story, Part 2

by Austin Xie, International Junior Research Associate, The University of Chicago, in conversation with Prof Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden

Austin Xie has spent two months at the Landecker Digital Memory Lab on the University of Sussex’s International Junior Research Associates (IJRA) programme. He tells us about what he’s learned and elaborates on the design of his own Holocaust-themed game, along with the ethical challenges he encountered.

Dr Victoria Richardson-Walden: you’ve been working on a practice-based research project considering the challenges and opportunities the medium of computer games might offer to Holocaust memory and education. What did you learn from studying existing games?

Austin Xie: The majority of Holocaust games fall into two categories: Nazi-killing games, and what I’d consider more Holocaust memory games than Holocaust games.

They take place after the Holocaust, and usually involve a character trying to uncover the story of a relative by investigating artefacts or talking to people. Their gameplay is that of remembering the Holocaust, rather than the Holocaust itself.

Games other than the Nazi-killing ones circumvent the problem of a Holocaust victim/survivor game through a variety of strategies, like setting the game after the Holocaust, creating a fictional world that is an allegory for the Holocaust, or focusing on resistance, like Through the Darkest of Times.

Many of the games also play more like interactive stories, where the player merely traverses scenes or text without making choices.

VGRW: Could you summarise some of the findings from the academic literature you read? What are the gaps in this writing?

AX: I think the most important finding is that people tend to be vague about what exactly the problems with the ‘Holocaust game’ are. Many seem to have misgivings about popular media in general, and in particular with associations with games, concerned that any work in these media will trivialize the Holocaust, or that making a Holocaust game turns it into entertainment, or ‘child’s play’.

Others think about issues like player agency/choice in a historical context, and how that might lead to players changing history. They use this observation to shut down the idea instead of ideating on how can you tell a history in a medium with agency?

It is not an impossible question, merely a design challenge and goal. This is where I think the gaps are. The literature does locate challenges and concerns with Holocaust game design, but does not attempt to solve them, rather avoiding them.

There are issues of representability: what one can show in a Holocaust game, what kinds of suffering and to what extent, as well as who one can be in a Holocaust game, obviously not as a Nazi, but the ethics of playing as, say, a survivor.

Does that become a hurtful identity tourism? Will players think that they have now personally experienced the Holocaust, or that they can genuinely relate to the traumatic experiences of survivors?

These are the main concerns I’ve found, although they were phrased as condemnations rather than as open design questions.

VGRW: Could you give us a summary of your proposal for a Holocaust game?

AX: The game involves traversing through scenes of survivor memory—you play as someone from the future who can enter memories and move into different memories that converge or connect from there.

For example, in the proposed game, a scene of memory from Holocaust educator and survivor Pinchas Gutter’s testimony where his family discusses what to do regarding Hitler, and considers emigrating to Israel, this could connect to other scenes of memory from other survivors, with family or even community discussions about the same topic or scenes of life already in the region.

The connections come at the end of the scene, through a selection of film reels that players can enter into, traversing either into memories of other survivors, or the next memory in Pinchas’s story.

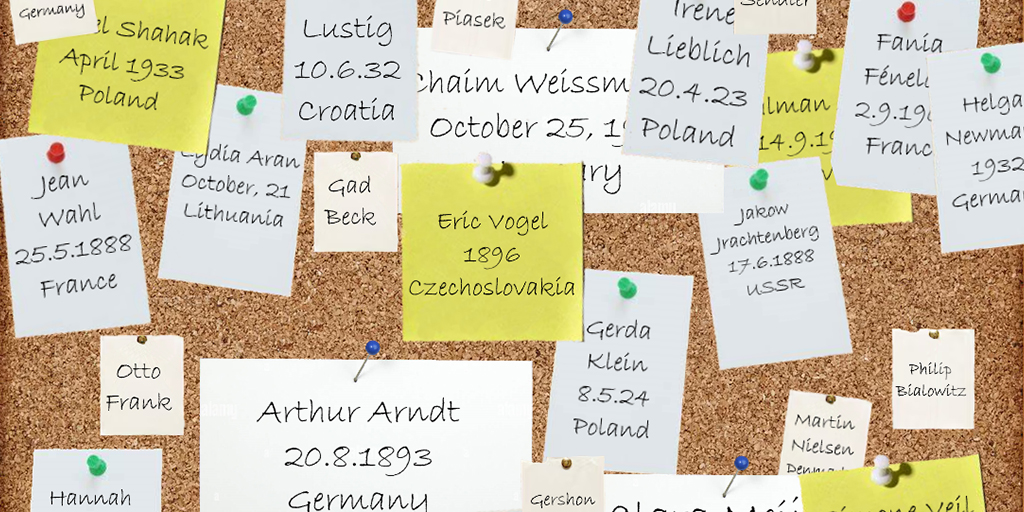

These scenes and connections would correspond to nodes and lines on a map that are drawn and expands as players traverse through more memories. The goal is to reach memories that contain information about missing people. Players would choose names for these people from a bulletin board at the beginning of the game.

One particular concern is that games can imply that Holocaust victims could have done ‘better’ had they simply ‘played the game well’, which felt severe to me.

VGRW: How did your research inform this game design?

AX: A lot of the design choices were made out of concern for the problems brought up by the literature. One particular concern is that games can imply that Holocaust victims could have done ‘better’ had they simply’ played the game well’, which felt severe to me.

This led me to eliminate that idea, hence the framing of a person from the future entering survivor memory, rather than playing as the survivor in a Holocaust ‘present’.

I chose a film aesthetic to support this by portraying the memories as something already set in stone that cannot be changed. Accordingly, player movements during the memories are completely unacknowledged to emphasize this. Walking around in the memory does not change anything, and neither people nor objects react to the player’s motions.

Concerns about representability also played a part. That was my reason behind the use of short scenes, so that they could fizzle out and not necessarily show everything. The disconnect this causes narratively also helps separate the content of scenes and make it more difficult to see them as options of choice for the survivor.

My research also showed me where challenges and gaps in interactive Holocaust memory projects are, as well as what digital Holocaust memory can do. I was particularly interested in the finding that people, when using interactive Holocaust kiosks (a screen with options to click on and read about), typically choose to read about something they already know, and then quickly lose interest and walk away (Reading 2003).

I wanted to solve this problem—as well as play into the idea that the scale of the Holocaust is better understood with knowledge of individuals and their stories—by making a game that requires players to learn about unknown stories and understand there is a variety of Holocaust experiences.

The idea of ’co-creation’ also played heavily into my idea of a map that is built as players play, rather than one that is slowly ‘revealed’, with greyed-out nodes and connections denoting where the player has yet to go. The act of making the map grow is part of the game’s communication of scale, and by contributing personally to that growth throughout the game, players should feel more strongly about it.

Austin’s academic poster, designed during his IJRA placement with us.

VGRW: In your previous writing, you’ve explored the idea of games as ‘spaces of possibilities.’ To what extent has this premise informed your design?

AX: I think games are a space where players can explore the possibilities available to them. I would say, arguably, that this is the essence of play.

My game design continues to follow that idea, but with the Holocaust as a possibility space—not because the game allows for changing the history, but because the Holocaust was, like anything, a possibility space; traversed by millions of people in a huge variety of ways. Exploring these possibilities is at the core of the game’s concept.

VGRW: What were the biggest ethical challenges you felt you faced during the design process?

AX: The biggest ethical challenge was by far the concern of implying that Holocaust survivors (since the game deals exclusively with survivor memory) could have chosen differently and done ‘better’. Although obviously they all survived, I was worried that players would see the experiences of different survivors and think that one had it ‘better’ or ‘less traumatic’ than another or made different choices.

I do not think this implication is completely eliminated, despite my best efforts, because putting survivor stories side by side fundamentally triggers this idea regardless of what the framing or the gameplay is.

I was also concerned about the idea of the game being ‘identity tourism’, but the framing, the exclusive use of short scenes and the fact that the game actually makes efforts to not immerse players into any particular survivor story at all, overcame that challenge.

VGRW: To what extent do you think your game design is successful, in terms of being a ‘playable game’ and as an ‘ethical Holocaust memory encounter’?

AX: It is a core tenet of good game design that one must playtest as early and as often as possible. But since this game is rooted in survivor testimony, making such a prototype would require a lot of research. Otherwise, a playtest would just be clicking around in a narrative-less space, creating a map of and exploring nothing.

Games in practice are almost always different than they are in theory—but I think it is an effective game, considering its gameplay similarities to IMMORTALITY, a game where players explore film clips to uncover a hidden story, and also its variety of Holocaust experiences.

I think it is also ethical. It uses real survivor testimonies and takes great care in maintaining their historical nature as well as not implying that those survivors could have chosen ‘better.’

The map and the effect of scale it brings would show the wide variety of circumstances more than the decision of any singular survivor, thus the game overall would steadily avoid that issue.

VGRW: What did you learn through this process?

AX: I learned a lot about teaching history and about the intricate implications of game design choices, and how difficult navigating sensitive subjects can be.

Especially, I learned that not every problem has a clever solution.

What to know more?