Capturing Experiential Authenticity at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

For many people, a visit to the Auschwitz Museum is a highly affective and important event. The thoughts, feelings and memories created during a visit constitute an authentic experience, which museumgoers are keen to capture and remember. This is often undertaken through the use of digital devices and social media posts – but what are the potential challenges of using technology onsite, and how does the Museum respond to this form of memory-making? On Holocaust Memorial Day 2021, we welcome guest blogger Imogen Dalziel, who explores these issues and suggests how the physical and digital can come together to further shape visitors’ experiences.

Auschwitz’s Authenticities

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum prides itself on being an ‘authentic site’ (e.g., Cywiński 2015). This term is oft used in public discourse to describe historical places, particularly those where atrocities happened. These sites provide material evidence of the tragedies enacted here. In academic literature, however, the concept of authenticity is a complicated one, long-debated and widely interpreted across a diverse range of academic fields, reaching far beyond ideas of what is real or true (see: Trilling 1972; Handler 1986; Phillips 1997; Lovell and Bull 2018, and others).

Due to spatial constraints, I shall not fully venture into this discussion in detail here, but instead cite Paweł Sawicki, Press Officer and spokesperson for the Auschwitz Museum, who in an interview for my research described the institution as having ‘two authenticities’:

- the authenticity of the physical remains of the site

- the authenticity of the survivors’ words.

I suggest both types can be understood through the umbrella term of curatorial authenticity. This encompasses authenticity that is defined through objective, scientific measures (Newman 2019; Wang 1999) and, in this case, witnessing actual historical events. Several tons of human hair, for example, were discovered on the grounds of the former camp after liberation. A sample was forensically tested and found to contain traces of hydrogen cyanide, providing proof of murder by poison gas and, therefore, the hair’s authenticity (Strzelecki 2000).

I would also add another type of authenticity in relation to the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum; that of experiential authenticity. This concept concerns the thoughts and feelings of the visitor as they tour the site, and the memories that remain after their visit, that lead them to consider their experience an authentic one. As Paul Williams (2010) writes:

While authentic experiences are difficult to objectively define, an experiential sense of some shade of existential transformation is known when it is felt.

Experiential authenticity is therefore wholly subjective and personal to each visitor. Here I propose two ways of understanding perceived experiential authenticity onsite. Firstly, for many, it is evident that simply being on the site itself, in the very places where significant events took place, constitutes an authentic experience. In several studies, participants have emphasised how integral their visit to the Museum has been in shaping and furthering their understanding of the history of Auschwitz and the Holocaust, and their incredulity at moving around a space where such atrocities were perpetrated (Thurnell-Read 2009; Dalziel 2016; Richardson 2019). This is perhaps best exemplified by a young backpacker quoted in Thomas Thurnell-Read’s (2009) research:

You stop and think, on this exact spot … this is where it happened […] this is what everyone talks about.

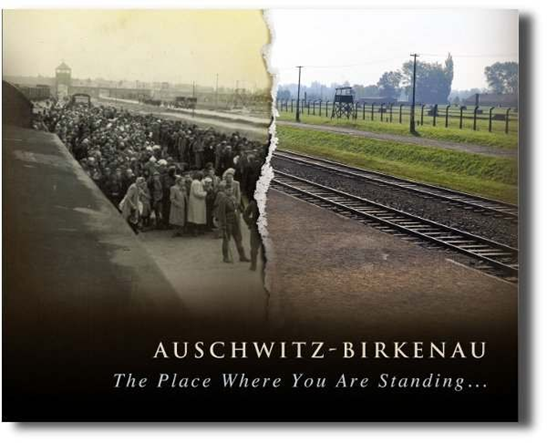

Furthermore, organisations such as the Holocaust Educational Trust (2020) advocate the importance of visiting the site in person, whilst the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum itself has acknowledged the impact of being physically present onsite through the publication of its photo album, The Place Where You Are Standing (Sawicki 2012).

Alternatively, a perceived authentic experience relates to the emotional impact a visit to the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum can have upon the individual. This is largely elicited through individualisation of the victims, and an emphasis on the ordinariness of those who were persecuted. At some level, this allows for a sense of identification with the victims, perhaps best illustrated by Alison Landsberg’s (2004) example of a ‘prosthetic relationship’ between visitors and Holocaust victims’ shoes:

At the very moment that we experience the shoes as their shoes – which could very well be our shoes – we feel our own shoes on our feet.

This is not to say that an authentic experience translates to an empathic or reconstructed historical experience; the focus remains on the visitor as they experience the contemporary Museum, rather than an attempted identification with what life was like in the camp. It is clear, however, that viewing the everyday possessions of murdered people creates an affective imprint which influences the visitors’ experience, both during and after the visit (Dalziel 2016).

Experiencing Auschwitz via the Digital

Visiting the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum undoubtedly leaves a strong impression on many who travel to the site. How can these authentic experiences best be captured for reflection and remembrance? In the digital age, portable devices such as cameras, tablets and smartphones allow visitors to further individualise their experience and create lasting memories with a simple click or tap. Photographs are taken and edited, videos are recorded, and social media are used to share visitors’ reactions to the Museum. Instead of obtaining physical souvenirs, museumgoers thus create ‘personal digital souvenirs’ with which to remember their visit to the former camp (Reading 2009).

Capturing memories and experiences through photography (and, increasingly, social media) is an established aspect of the ‘performance’ of touring and visiting sites (Bærenholdt, Haldrup and Urry 2004). Yet this creates a certain degree of tension between visitors and the Auschwitz Museum. Because of its status as a well-preserved, ‘authentic site’, the Museum is keen to discourage visitors from using digital devices around the grounds. In the permanent exhibition, the focus remains on physical artefacts and buildings (the national exhibitions, I argue, constitute ‘micro-museums’ within the Museum, so any technology included in these displays are not directly affiliated with the host institution). Director Piotr Cywiński (2015) has also made it clear that this approach will not change when the new permanent exhibition opens over the next several years.

Nevertheless, visitors to the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum take photographs for a variety of reasons (Dalziel 2016; Hilmar 2016). Yet the personal, ‘privatized and interiorized’ nature of photography and social media content means people’s motivations for, and interpretations of, their use are rendered ‘inaccessible’ to others, creating ‘moral anxieties’ for the average observer (Livingstone 2004). The most controversial images include (predominantly younger) visitors, most notably selfies; social media users and the international press have responded with outrage and criticism each time one of these photographs has gone viral (Drewett 2017; Parker 2019; Frazer 2019).

Some of these photographs are, undoubtedly, taken to cause provocation or offence. Others, however, may form part of the desire to capture the visitor’s authentic experience. By including themselves in the frame, visitors create a ‘certificate of presence’ (Barthes 1993) at the site, and may attribute certain thoughts or emotions to different photographs. American teenager Breanna Mitchell, for example – whose ‘Auschwitz selfie’ went viral in 2014 – defended her actions by stating the image was a tribute to her late father, who shared her interest in Holocaust history (Durando 2014). For Mitchell, the experience of visiting the Museum – somewhere she had wanted to see with her father – was encapsulated in that image.

This is not to deny that there are issues with some of the photographs taken at the Auschwitz Museum and how these are published and captioned on social media. The surge in Holocaust tourism over the last 20 years, and the notion that the site is a ‘bucket list’ location, has led to some visitors treating their time at the institution no differently to that spent in museums and cultural institutions of a lighter nature. What is clear, however, is the need for a public conversation regarding the ways in which visitors capture their authentic experiences – not just at the Auschwitz Museum, but across other sites deemed ‘dark tourism’ destinations (Lennon and Foley 2000). Taking pictures is far better than, for example, attempting to remove physical elements of the site as souvenirs, as has happened on several occasions (Day 2014; BBC News, 2015). Furthermore, as Carmelle Stephens (2020) argues in response to the recent TikTok #holocaustchallenge controversy:

engaging the interest of children and teenagers in preserving the memory of the Holocaust is vital.

Dismissing their initial responses outright is inherently counterproductive. Digital Holocaust Memory also covered this controversy in a previous post.

Although the Auschwitz Museum is reluctant to promote the use of digital devices onsite, perhaps a mediated educational approach involving photography and social media would help visitors use these tools more mindfully. A series of ‘Tweetups’ at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, in which participants were invited to post their impressions of the former camp on social media during a guided tour, resulted in greater awareness of content production and fewer images that some might deem offensive (Schoder 2016). As the Auschwitz Museum has relied on the Internet to educate and interact with the public over the course of the pandemic, perhaps, as visitors return to the grounds, it is time to combine physical and digital elements to open up this conversation and allow visitors to feel comfortable in capturing their important authentic Museum experiences.

Dr Imogen Dalziel is Programme Co-ordinator for the Holocaust and Genocide Research Partnership; Administrator for the Holocaust Research Institute at Royal Holloway, University of London; and a Freelance Educator for the Holocaust Educational Trust. She is also currently undertaking a family history research project for a private client. Imogen’s research interests centre around Holocaust tourism, digital Holocaust memory, and the spaces in which the two intersect.

What to Know More?