Debunking Digital Myths

Debunking Digital Myths

Last night, I was very honoured to present some initial ideas related to my research about digital Holocaust memory for The Cape Town Holocaust and Genocide Centre. In today’s blog, I thought I would summarise some of my main arguments and draw attention to various digital Holocaust memory projects, which you may want to explore further. As I said in my introduction to the talk, this work is at its very early stages, so these really are ruminations to be taken further in the next few years.

1. We should be sceptical of claims that the digital is innovative and new

In a 2016 article published in the academic journal New Media and Society, Michael Stevenson maps what he calls the ‘belief in the new’ through the 1990s dot.com era to the emergence of Web 2.0. In the case of the latter, there was a belief that social media would make broadcast media obsolete; we have entered the ‘digital age’, or so we are told.

Stevenson notes the impact cyberculture magazines Mondo 2000 and Wired had on creating the discourse of the new – if we wanted to be ‘digital natives’, then we had to learn the lingo of tech-speak and emojis (so no one is really a ‘digital natives’ at all). Otherwise, we’d be left out of this new, exciting digital community.

So, we embraced the digital as the next best thing, as the radical media that was going to change our world in innovative ways because that’s how it was sold to us by cultural intermedialities – the influencers defining this new field.

The question I am interested in is do digital interventions in memorial museums and archives always offer something new – something particularly computational – to their memory and education practices? In the next three points, I focus on three key terms often considered specific to the digital and try to show how they both exist in pre-digital forms and may not always be present in digital projects: interactivity, virtuality and immersion.

2. Interactivity

What does it mean to be interactive? Has the digital ushered in an age of the ‘active user’ in place of the historical ‘passive viewer’?

Those working in media and film studies will be familiar with my answer to these questions – which are not new:

- Activity, i.e. moving the body, does not necessarily mean we are being interactive in a participatory sense

- Neither does the fact we might be able to produce content, if we are not being empowered by taking on this creative role

- We have always been active audiences, mentally and bodily. So, what implications do these arguments have for memorial museums and archives?

- To what extent do ‘interactive projects’ shift the power relations between curator and visitor?

- Can we move from Institutional Memory to Collaborative Memory?

- What are the implications of doing this?

- How might interactivity be used to empower visitors/users to become producers of memory – to take on the political and ethical responsibility for continuing memory of the Holocaust?

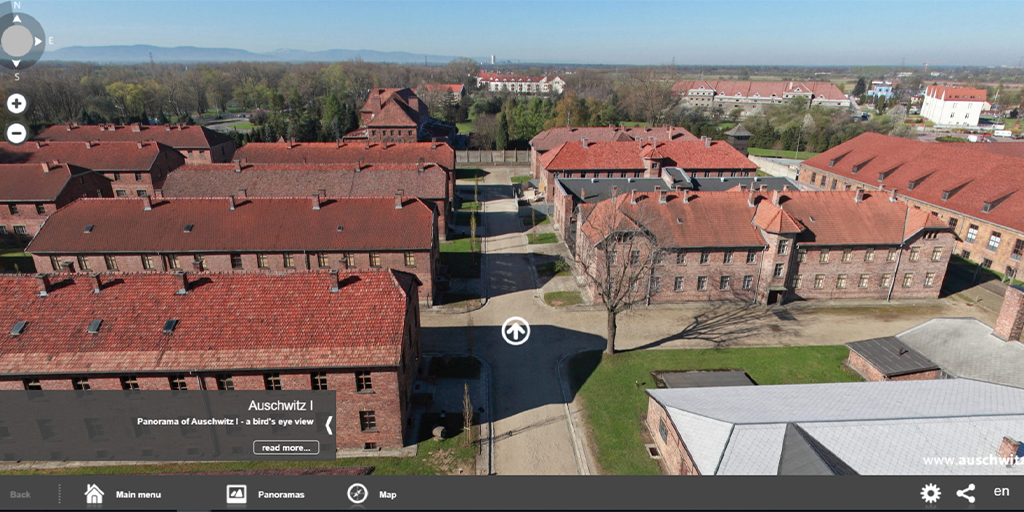

One example I mentioned last night which presents interactivity in terms of allowing the visitors to click on things but is not interactive in the sense of empowering us to participate in the production of memory is the Virtual Tour of Auschwitz available online. Just as with the physical memorial site our visit is heavily curated by the permissable directions programmed into the application. Nevertheless, at the current moment, it is a particularly valuable resource given we cannot visit the actual museum site.

Screenshot of the virtual tour of Auschwitz State Museum

A different example, one that positions the user between past and present, and between representation and the lived-world, is the Here: Spaces of Memory augmented reality app at the Bergen-Belsen Memorial, which I discussed in my previous blog. Such an embodied engagment encourages the visitor to become actively enfolded into the process of producing memory; it encourages an inquisitive, archaeological, searching gaze.

There are of course, also quite radical forms of interactivity being introduced into museology – one example is the Participatory Museum Manifesto which encourages active engagement of visitors in curational practices without necessitating digital techonlogies.

3. Virtuality

In my previous work, I understand the virtual through Bergson and Deleuze. For Bergson, every moment has its actual as it moves into the future and its virtual as it moves into the past. Deleuze thinks about this in relation to cinematic representation in regards to the extent to which any moment can ever been entirely re-actualised. Some representations attempt to present a reactualisation, others draw attention to the fact that past moments remain in the past.

Here: Space of Memory is one example in which virtuality is brought to the foreground – in which we are reminded that we cannot fully time-travel back into the past as if we can ‘walk in the footsteps’ of those who suffered here. However, pre-digital technologies are also just as capable of drawing attention to the complex temporal dimensions of memory.

Another example of this, then, is the analogue hologram exhibition previously at the Jewish Museum Vienna. The displays showed holographic copies of objects of Jewish life in the pre-war period, including the early days of the Anschluss. As the visitor moves around the exhibition, these holographic images appear and then disappear from their perceptual horizon dependent on how and where they move. This act of creating ghostly presences and disappearances evokes a memory of the Holocaust as much as it tells us about pre-war Jewish life.

4. Immersion

In her extensive work on museums and historical forms of immersive space, Alison Griffiths (2013, 257) defines this term (as others have also done) in relation to ‘total environments’ which create:

the sense of being in close communion with something other than the here and now, something that takes us into a ‘virtual’ reality that could be defined by the interstitial space where we are never fully ‘there’ because our bodies can never fully leave the ‘here’.

Striking in her work, is the fact that immersion has long been embedded within our culture. Indeed she traces it back to religious spaces like cathedrals. Whilst Griffiths and others relate the terms ‘immersion’ and ‘virtuality’, I argue that ‘total environments’ actually resist drawing attention to the virtual, in a Bergsonian sense of the word. They give as a momentary impression of leaving our lived-world environment for a simulation space. Thus, they do not necessarily position us in an inbetween or interstitial critical place, but rather take us elsewhere.

Yet, whilst I have generally considered projects that draw attention to the split between the virtual and (re)actualisation as highlighting discontinuity, my colleague Beatrice Fazi (2018) has rightly noted that many digital media theorists read the virtual in relation to the continuity of affect, sensation and time (see for example Mark Hansen 2004). Yet, as Fazi argues the computational is fundamentally discrete – interruption, difference and discontinuity, then, might be ways of doing Holocaust memory that are particularly digital. Whilst, I do not think this claim removes the potential for digital projects to draw attention to the virtual dimensions of memory as I have previously described them, it does seem to challenge the significance of immersion (as ‘total environment’) to the computational.

Indeed, last night, I drew attention to two contrasting examples:

The first, is what I call ‘living history environments’ in Holocaust museums – for example as seen at Yad Vashem and POLIN (links to the virtual exhibitions included here). These physical exhibition spaces create simulations or ‘total environments’ of ghetto streets or other historical scenes. Although they do not prevent ‘living history’ in the way so-called ‘living history museums’ do (which use actors to perform characters from the past), they are nevertheless not deadened spaces as they require the visitor to walk through them, as if ‘walking in the footsteps’ of those from the past. Jennifer Hansen-Glucklich (2014) has discussed how museum objects can create a bridge between past and present which encourages empathy between visitors and victims. However, this raises two questions for me:

- (1) is empathy with victims the most productive way to encourage people to continue to remember the Holocaust and to learn ethical lessons from it (if indeed ethical lessons are to be learn as the purpose of memorial museums supposes (Amy Sodaro, 2018))? (A counter argument would be that encouraging visitors to consider the choices they might make when faced with the persecution of others in their community, might be more useful)

- 2) Hansen-Glucklich speaks about real objects, so to what extent can simulations have the same bridging effect and affect?

In contrast, the USC Shoah Foundation’s The Last Goodbye VR experience might on the surface suggest it will offer an ‘immersive’, ‘total environment’ as this is what most people have come to expect of virtual reality thanks to the way it has been marketed to us, and it is positioned in a separate room specifically designed for the experience. Nevertheless, its amalgamation of testimony, graphic representations (such as a cattle car decontextualised against a black background, and photogrammetry representations of the camp as a memory space which a survivor explores, not as a functioning concentration camp) suggests it is rather more interesting in drawing us into a space inbetween past and present, representation and the real, here and there, and the virtual and the actual.

You will note the use of words like ‘innovative’, ‘immersion’ and descriptions of the experience as ‘being in the concentration camp’ and ‘being in the gas chamber’ in the above video – promotional materials continuously return to these ideas to describe virtual reality experiences. Nevertheless, I think The Last Goodbye is far more sophisticated in the ways in which it expresses and enables computational Holocaust memory than this video might suggest.

Furthermore, whilst I argued above that the virtual tour of Auschwitz does not present interactivity in the sense of empowering the user, it does however, suggest a discontinuous computational logic which could be interesting for thinking about the entanglement between human and machine in digital memory. (I will explore this further in a later blog).

Further ruminations …

In the brief Q&A that followed yesterday’s session, we spoke about the implications of ‘cutting and pasting’ survivor testimony [in relation to the Visual History Archives’ I Witness project].

Screenshot of the I Witness home page. (Images are replicated here under fair-use and educational purposes, and to encourage people to view these resources. No profit is made from this blog project).

I think this brings up some really interesting questions and identifies different ways in which we can think about what testimony is and who it is for? I’m really thankful for this question, which got me thinking a lot this morning. Here are some initial ruminations:

- If testimony is about retaining the story of the individual witness for their family, community, and for wider evidentiary and educational uses, then retaining it as a unified, complete narrative is incredibly important. When we are facing increasing Holocaust denial, evidence seems a vital tool for memorial museums and archives – perhaps even more so than before.

- I Witness, however, does not damage the original – the testimony as it was recorded and archived can always be re-viewed. This is one of the great things about digital and other electronic media forms. They are not only inscription media, like their earlier counterparts, but they can be copied, copies can be made from the copies and each copy can be varied without altering the original. Lev Manovich (2001) calls this variability and has argued that it is one of the specifics of computational media (although it is also arguably true of earlier forms like celluloid film and photography).

- I Witness enables a kind of network thinking that we might identify as particularly computational or digital. There is always the danger that one testimony or diary, say for example that written by Anne Frank can become a metonym for ‘the Holocaust’ just as Auschwitz seems to have become in the popular imagination. Indeed, as Todd Presner (2017) has argued, people often look for the same names and topics in the Virtual History Archive. If Anne Frank or Auschwitz represent ‘the Holocaust’ to people, then the complexities of this vast number of historical moments will fade from public consciousness (indeed, research suggests that young people’s knowledge about the Holocaust is already minimal).

- Network thinking allows users to see numerous different witness responses to key words, say for example ‘hunger’ or ‘roll call’. It embraces the multi-vocality of memory and resists the notion that ‘the Holocaust’ can be reduced to a simplistic, neat singular narrative. It also requires that the user makes choices about how to construct a memory narrative that is meaningful to them through multimedia editing software.

- However, I come to this topic aware of my own biases and background – I think and write from a memory studies perspective, yet those interested in knowledge and history look at things differently. Are more simple narratives useful as a way of broadcasting knowledge?

There is of course nothing wrong with using the digital as a broadcast media. In fact, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s (1999) book Remediation argues that perhaps what is actually new about so-called ‘new media’ is the very fact that it is not particularly new at all, but rather that it relies on remediating older media forms. Nevertheless, what I hope to achieve with this research is to think about ways in which the essences and logics of the computational could truly offer something radical to Holocaust memory, which might help define the shift as we move from an age dominated by ‘living memory’ to one of ‘mediated memory’ only (James Young, 2000).

Want to read more?

Commemorating the liberation of Bergen-Belsen digitally

Call for support creating a Covid-19 archive of digital resources

What’s in a name? Naming Holocaust research projects on social media