Finding Virtuality in Virtual Holocaust Museums

Lockdown is here again, for many of us. As museums, cultural and heritage centres close their doors again, this week’s blog reflects on what is a virtual museum, and offers various links to different experiences that you might want to ‘visit’ (in lieu of in-person trips) or share with students.

What is ‘virtual’ about virtual museums? Virtuality is so frequently used interchangeably with digital, it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish whether a museum – or indeed any other online experience – is trying to present itself as a virtual experience or a specifically digital one, or indeed both!

Attempts to virtually transport users into photographic, videographic, or photogrammetry representations of physical museum sites can often feel like remediations of in-person experiences of visiting museums as we are offered limited navigational paths through the exhibits. The main difference is that online we move representations towards us by clicking on arrows or highlighted content rather than moving our bodies closer to them, as we do in the physical space.

Whilst remediated experiences of physical exhibition spaces have become particularly popular during the pandemic, given we cannot see them in-person, there are many forms of virtual museums, some of which are digitally-born forms that have no non-computational copy, although they still rely on physical items form museum collections, and often present these in multimedia displays not unlike their exhibition hall counterparts.

In this week’s blog, I introduce a brief discussion of virtuality, before a close reading of four different examples of virtual Holocaust museums. Embed in each case study are a number of links to other examples. Please do share your experiences of ‘visiting’ them in the comments.

Virtuality

Whilst in public discourse virtuality is used as a synonym for digital, in cultural theory and philosophy it has been discussed with more nuance, often through a Deleuzian lens. Bear with me here, for the theoretically dense bit of the blog.

Many scholars have come to the idea of virtuality through Deleuze in relation to either memory or affect. I have written in detail, in a 2019 article published in Memory Studies about the significance of the virtual to temporality and memory. For Deleuze, any moment splits into the actual and the virtual – the present and the moment transforming into pastness. When we try to relate to the past through memory, we can never retrieve any moment in its fullness, i.e. both its virtual and actual, rather we attempt to re-actualise it in the present. It takes on a different form to its original, as memory. Nevertheless, acknowledging the virtuality of moments can be a transparent way to engage with the past through memory, i.e. highlighting that we cannot simple ‘follow in the footsteps’ of our ancestors, or ‘relive their experiences’ (cliché phrases I am sure we have all heard). Thus, I have argued that it is better to think of virtual Holocaust memory as a methodology for memory practice that can be adopted in digtial or non-digital projects, rather than simply another way of saying ‘digital Holocaust memory’.

In relation to temporality, we can also understand the virtual through Bergson’s reading of the Zeno Paradox in which, for Bergson, the arrow does not simply move from point to point, but as it moves through time and space it opens up to undefined potentialities. These potentialities may or may not materialise into actual experiences, regardless potentiality is a real if not tangible dimension of lived experience.

Cultural theorists like Brian Massumi focus more on the relationship between affect and the virtual in Deleuzian thought. Massumi argues that

Affects are virtual synesthetic perspectives anchored in (and functionally limited by) the actually existing, particular things that embody them.

Here, affects are not concrete, but abstract; however, they are not transcendent of lived experienced; they are essential to it. For Massumi, affect can escape the confinement of any particular body and can be captured and closed, for example as expressed by emotion.

Affect, temporality and memory are these muddied, fluid dimensions of experience that are familiar, but remain difficult if not impossible to fully translate into language or other systems of representation which attempt to fix both meaning and flow. They are not concrete or tangible, we cannot hold them in our hands, we can not see, hear or smell them as definable sense-data, they rely on continuous movement, passing through space and time, and in-betweenness – between bodies, things, and moments. We should then be sceptical of the idea of virtual representation – virtuality resists the closedness of representation. Yet, as Massumi eloquently argues:

The virtual, as such, is inaccessible to the senses. This does not, however, preclude figuring it, in the sense of constructing images of it. The contrary, it requires a multiplication of images. The virtual that cannot be felt also cannot be felt, in its effects. When expressions of its effects are multiplied, the virtual fleetingly appears. Its fleeting is in the cracks between the surfaces around the images.

Images of the virtual make the virtual appear not in their content or form, but in fleeting, in their sequencing or sampling. The appearance of the virtual is in the twists and folds of formed content, in the movement from one sample to another. It is in the ins and outs of imaging. (…) No one kind of image, let alone any one image, can render the virtual.

One way we can draw attention to the virtual, Massumi claims, is through imagining ‘infoldings and outfoldings, redoublings and reductions’ and in between images (p133). I have also argued that screen experiences related to Holocaust memory can foreground virtuality by drawing attention to in-betweenness through intermediality, exposing the spaces were flow and relationality can happen, where potentialities lie, where emergence is possible.

Perhaps most striking in Massumi’s book is his argument that ‘imagination is the mode of thought most precisely suited to the differentiating vagueness of the virtual’ (p134), which echoes Didi-Huberman’s claims about collective memory of the Holocaust – those of us who did not experience it can only access it through imagination. It is therefore vital that representations aimed at encouraging future generations to take on responsibility for memory, stimulate their imaginations. Thinking about memory through virtuality and affect suggests that imagination can be provoked by opening up spaces for potentiality.

Whilst Massumi reads affect in terms of the ‘continuously variable impulse or momentum’ of the analogue (p135), Mark B. Hansen, Beatrice Fazi and others argue that despite the discreteness and discontinuity of the computational, the digital can still be understood in terms of affect, and therefore in relation to the actual and the virtual. However, I do not have time to engage with this extensive debate here. Nevertheless, like these thinkers I was sceptical of this association of the analogue with virtuality. Reflecting on Virtual Holocaust Museums has, however, encouraged me to think again.

Massumi argues vehemently against the idea that the digital possesses potentiality, understanding the limitations of coding as offering only a fixed number of programmed possibilities rather than the openness of potentiality (p137). Relating the digital to the virtual, he argues, ‘confuses the really apparitional with the artificial. It reduces it to a simulation’ (p137).

Unlike Massumi, I do believe we can find potentiality in digital experiences, but there is a strong case to be made for the fact that many understandings of digital virtuality really refer to simulations of physical environments or experiences, an as if we were there scenario, rather than drawing attention to the very virtuality immanent in lived-experience through affect, temporality and memory. Massumi goes onto argue that ‘digital technologies have a connection to the potential and the virtual only through the analog’ (p138).

In a future blog and forthcoming publication, I explore how the paradigm of Mixed Reality – which despite his positioning against Massumi as an advocate for digital affect, Hansen argues is the essence of all reality – might be more productive for thinking about digital Holocaust memory projects than aiming to create ‘immersion’. There is certainly a provocation of emergence, potentiality and in-betweenness that appears when memory projects fuse together physical and digital elements. Indeed, Massumi sees potential promise in the idea of interfaces being embedded into everyday environments (p142), though he falls into the trap of considering this immersion.

Although, as Massumi highlights, our encounters with the digital generally enfold the analogue, from scans of photographs to uploaded video or sound, to reading language on screens (p139-42) – these are often analogue experiences codified and processed digitally. Where they are more specific to the digital, as in the case of surfing the web, he argues the potentiality is not a result of the ‘coding itself, but of its detour into the analog. The processing may be digital – but the analog is the process’ (p142). When we surf, we mentally and physically move ourselves through different online spaces.

This brief reflection on virtuality raises some questions in the context of virtual Holocaust museums:

- What is virtual and affective about our ‘visits’ to virtual Holocaust museums then

- Do virtuality and affects emerge from new forms of in-betweenness defined by different parameters?

- Or are they essentially just simulations of physical visits?

- Do such experiences open up spaces of potentiality? Do they encourage us to acknowledge a movement between past and present and thus to explicitly engage in memory processes?

These are the questions that lay at the back of my mind as I went about exploring a number of different virtual Holocaust museums. In the following readings, I do not promise concrete answers, but emerging reflections on the relationship between these experiences, virtuality, affect and memory.

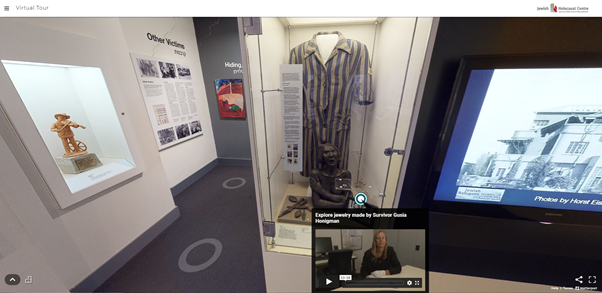

Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne – Virtual Tour

The Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne is, subject to the pandemic, undergoing a relocation. Therefore, even before Covid restrictions came into action, the Centre was facing a planned closure in 2020. The virtual tour serves as an archive of a now historic exhibition, but also as a way of exploring the collection whilst the Centre temporarily has no physical public space. On the one hand, the virtual tour simulates the exhibition as it was, giving the impression as if we are there through a detailed photographic presentation of the space which is navigational by clicking on directional arrows. On the other hand, one cannot experience all of the exhibition as if we were there. Instead certain discrete multimedia points are embedded into the image, which can be enlarged and viewed, whilst other elements cannot be investigated as closely as one might do in the physical exhibition.

To give some examples:

- There is a large model of Treblinka by survivor Chaim Sztajer which has an accompanying video. I felt myself wanting to inspect this monumental yet personal artefact from angles that were not available to me in the exhibition – limited by the vectoral movement enabled by clicking on the directional areas. If Bergson read affect as the passage through space and time in Zeno’s Paradox rather than from point to point, here movement really was presented as point to point, as is inherent to computationally-coded space.

- The Google maps-like mechanics of many virtual tours can leave one feeling disorientated. We cannot always interact with the elements that are interactive in the physical space, i.e. smaller displays can be difficult to read, we cannot pull open drawers or click on screens within the exhibition. Digital content has instead been curated for us as a layer on top of the image of the exhibition space which we can access by clicking on markers like we are exploring a map.

- Yet, some of the videos allow me to go behind the scenes and penetrate the walls of the museum into the archives with archivist Jayne Josen, who discusses the stories behind specific objects on display. Jayne holds each object with white protective gloves and tells us about them. Thus, I feel like I get an exclusive view that I suppose visitors to the physical exhibition were not privy.

- There are also videos explaining memorial projects created by young Australian children (Bialik Button Project) and videos of survivors introducing elements of the exhibition, for example Survivor Rosa Krakowski introduces a photograph of her and friends wearing white arm bands in a ghetto in Nazi-occupied Poland, which seem to extent the stillness of the physical display.

- I could also zoom into some of the objects on display.

I was not fortunate enough to have the pleasure of visiting the Centre before its closure. So, I found myself wondering whether the videos I was watching were also available on the screens embedded in the exhibition (which I could see in the ‘virtual museum’, but with which here I could not interact). Perhaps they are. However, I am aware that such displays have been used to present the Storypods content which is also available as an iPad app enabling visitors to learn more about Holocaust survivors through a number of objects beyond the limitations of what can be displayed in the exhibition space.

What is certainly distinct about the online presentation of these videos, however, is that they link out to YouTube (a convenient platform for embedding video content online). This is a recurring element I have seen in many virtual museums and tours, and I am continually fascinated with how we might negotiate control with the Platform’s algorithms over curating the ‘up next’ list, which could expand the Centre’s narrative ever further truly into a networked, ‘Museum without Walls’ which opens up endless potentiality. There are some ways to do this, such as creating Playlists and naming videos ‘Part 1’, ‘Part 2’, ‘Part 3’ etc., however this still continues curational control and the videos do not always come up in order via the ‘up next’ column. Journalist content, such as that provided by Aljazeera for the Srebrenica Virtual Museum leads to other news sources designated as reputable by YouTube. Perhaps there is a way to work with Google and YouTube to draw viewers to a range of sources created by different institutions and individuals via this panel? ‘Up Next’ seems like a messy and often problematic hyperlink junkyard on YouTube – a missed opportunity for collaborative memory production.

There is something distinctly noticeable about my ‘visit’ to the JHC virtual museum and that is the silence. I could not hear the subtle sounds of the museum space, which we so often think wrongly is silent: the rustling and footsteps of others, that one visitor who responds loudly to exhibits (we have all had this experience, I think!), ambient music or sounds of other displays that give depth and texture to the place’s dimensions. Although depth is represented in the images, aurally the experience is flattened.

The strange, staccato movements that enable me to get closer to objects feel very nonorganic and each step is a discrete sweep from position A to position B, moving across a vector which feels particularly digital. Yet, my navigation through the exhibition simulation highlights objects and stories foregrounded through the narratives of display panels and the embedded content. Even though the videos and other content are decontextualised as discrete elements that pop-up from the represented image of the museum space, they draw attention to the analogue elements familiar to Holocaust museology and memorialisation: material evidence and human stories. It is not the digital interface that creates affect, in fact the aural flatness and vectorial motion I described above can actually make this feel quite alienating as a memory space, but rather it is the inherent analogue nature of the experience.

It might be wonder whether the physicality and materiality we so often consider so central to the museum experience and its collection and display of objects is really the most defining element of the ‘museum’. Memorial museums, such as those about the Holocaust, trade in human stories often stimulated by objects, but do we need to be in the same physical space as the things to connect with these human experiences?

Other Examples of Virtual Tours:

- The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s virtual tour for students is available as a 360 degree computer experience or in VR via the Google Expedition App

- Dallas Holocaust Museum and Learning Center

- Take a tour of the Arolsen Archives

You can experience 360 tours of memorial sites too:

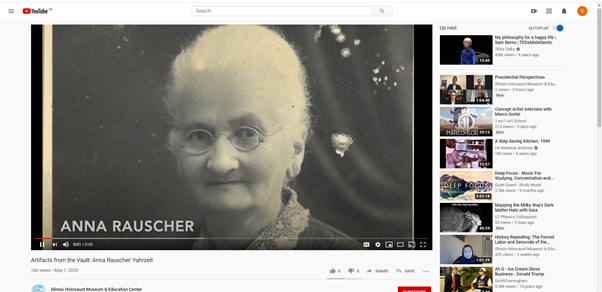

The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center’s Virtual Museum

This site takes a different approach to the idea of the ‘virtual museum’. Rather than simulate the physical exhibition space, it fragments media otherwise available there. For example, it offers snippets of the museum’s audio tour each accompanied by photographs of objects featured in the related exhibition hall. However, the narration refers to the objects we are going to see and the doors we will walk through and directs us left or right towards the next audio point. However, we will not see these things. Rather than give us the impression as if we are there or create a digitally-born exhibition, this virtual museum rather hints at what we could experience in the physical exhibition. It retains a distance between our ‘virtual’ encounter with the collection and the experience of visiting the concrete site. Online, we can only access fragments of its counterpart.

The full audio tour is also available via Google Play or the Apple Store.

Next, I can visit a page with a selection of videos curated by Registrar Emily Mohney where ‘she tells stories of unique artifacts that are not on display in the Museum’. The videos are 35-50 minutes long – perfect for sharing on social media platforms, where they could be used to stimulate discussion. As with the video content shared by the JHC, once again the YouTube embed code allows me to watch the content directly on the Google-owned Platform. Here, we can see that muddied mix of content available via the ‘Up Next’ column again – a combination of videos that will either extent my knowledge and interest in the Holocaust or completely distract me from it.

The videos often start with a slow zoom shot revealing the object, this is followed by photographs of the owner and any other archival content related to their story, before returning to the object to finish. Emily does not appear in the videos, she narrates in voiceover.

The continually moving camera encourages a close-up look at objects, including photographs, newspapers, a spoon, wallet and more. The narrative complements the camera movements by drawing us both outwards from objects, i.e. giving us historical context and zooming in, by explaining details about individuals. These feelings of movement provoke affect by drawing together socio-cultural circumstances, places, objects, and human stories. The refusal of stillness reminds us of the movement inherent to both affect and memory. The objects do not simply materialise the past as if it was here before us, but rather the contemporary voice and camera motion foreground the negotiation between past and present involved in the process of remembering.

After these more discrete, fragmentary introductions to elements both in and behind the scenes of the physical exhibition, follows a 3 min 56 sec video tour with Chief Curator Arielle Weininger. By clicking through to the YouTube page for the video, it is clear this was not designed specifically for lockdown, but rather, like much of the material gathered on the Virtual Museum page, it is from their multimedia archive. The tour was originally designed for Women’s History Month 2018 and focuses specifically on objects and experiences of women. The tour starts with an establishing shot of the Center’s exterior then introduces Arielle standing next to the Center’s sign which features its name and slogan: ‘Take history to heart. Take a stand for humanity’. A short montage using dissolves between shots creates a sense of moving through galleries before the tour proper begins. Many of the sequences start with Arielle walking into shot, as is conventionally used to create depth and a sense of movement across images in filmmaking. Individual objects are presented in close-up as she discusses the story of a number of female Jews who had different experiences of the Holocaust, from the Shanghai Ghetto to Bergen-Belsen. Whilst the tour has a non-diegetic soundtrack added, at times the murmuring of the exhibition’s offscreen crowds can be heard. Here, objects as they are displayed in the physical museum are the focal point.

Although recorded, the tour is reminiscent of the themed, bite-size live-streamed walk-throughs several concentration camps have presented on Instagram and other social media platforms during lockdown. Follow Bergen-Belsen, Neuengamme and Dachau on Instagram and Facebook for any potential future events. See our previous blog on the Bergen-Belsen Anne Frank Instagram tour.

Walk-through tours are deeply rooted in specific physical spaces, but online, the audience is detached from the geographical orientation of these places. Yet, the walking, which we often see on-camera (as illustrated in both the Illinois and Bergen-Belsen examples) foregrounds movement. Is this movement essential to digital expression? Well, on one hand, of course not. The Illinois Virtual Museum otherwise perfectly illustrates the discrete aesthetics inherent to the digital. Yet, watching human movement through ‘authentic’, physical historical or cultural spaces online returns us to that analogue sense of intensity and flow that Massumi described. The analogue that provokes potentiality and affect.

Perhaps this explains why one viewer of the Anne Frank Instagram of Bergen-Belsen asked for the guide Tessa Bouwman to move to a different place in the site to accomodate their desire to see the memorial marker for Anne. The sense of movement provokes potentiality – the tour’s steps are not fixed, they can be changed. This is of course true of guided tours at sites, to some extent, where visitor questions might initiate a slight change, although never entirely off the original guide’s script or plan. However, in the Illinois example, the walk through is limited in terms of potentiality because it is a pre-recorded experience. Although we see glimpses of various exhibitions spaces, what we can look at in detail is restricted by the curated experience as framed by the camera and narration.

The Illinois Virtual Museum also includes a virtual exhibition: Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the exhibition’s closing video, and a sample of survivor documentaries. Further fragmented and discrete elements of the Center as a whole.

The Florida Holocaust Museum’s Virtual Tour combines a map with photo galleries. Here, users can select which areas of the exhibition they want to view.

For another example of a walk through virtual tour, check out this YouTube video through the core exhibition of POLIN which untypically visually features neither guide nor the physical museum space, but rather a digital interpretation of the exhibition accompanied by voiceover.

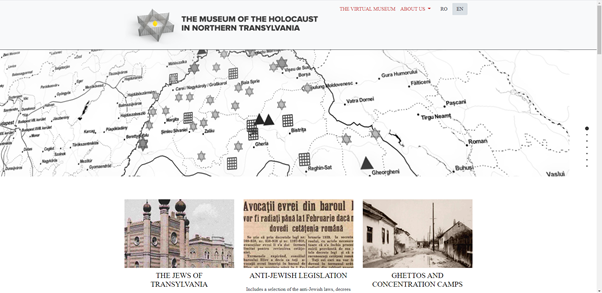

The Virtual Exhibition

There are plenty of examples of online Holocaust exhibitions, not least the several institutions represented on Google Arts and Culture (Stories of the Holocaust is an exhibition created by several organisations, but you can also ‘visit’ specific museums on the platform). Others, such as the recently launched projects Sobibór on the Screen and Compromised Identities were specifically turned into online offerings during the pandemic. They do not, however, claim to be virtual museums. In contrast, The Museum of the Holocaust in Northern Transylvania (The MHNT) does, indeed it claims to be the ‘first’ virtual Holocaust museum.

What does such a claim mean?

- There exist a multitude of online exhibitions about the Holocaust. Does it mean the first ONLY-virtual museum, i.e. one that does not have a physical space attached it to it?

- How is it ‘virtual’ and how does it conceptualise the idea of the ‘museum’?

The MHNT is not dissimilar to the many Google Arts and Culture sites mentioned above. It is divided into five exhibitions and describes itself as ‘an interactive museum’ (I’ll be exploring different types of interactivity in digital Holocaust memory projects in a forthcoming blog). Each exhibition is presented as part of a text and image website. The structure and multimedia mix are not dissimilar from a display board in a physical exhibition. Certain names or things are hyperlinked in the text, which take one to a gallery image of that person or object. With one click, you can zoom in, another click, zooms out. There is also an option to see the image full-screen. Below this, one finds an embedded pdf of the photograph of the object, which can be downloaded or printed, and is accompanied by key archival details about the object: ‘Title’, ‘Description’, ‘Creator’, ‘Source’, ‘Date’, ‘Relation’, ‘Language’, ‘Collection’, ‘Tags’ and ‘Citation’. The collection is hyperlinked, and a click here takes you to the other sources in this collection. In the exhibition ‘Ghettos and Concentration Camps’, there are no longer hyperlinks and less photographs, but these pages do include maps that one can zoom in and out.

This example of a ‘virtual museum’ troubles traditional conceptualisations of both terms: ‘virtual’ and ‘museum’. The images and text foreground linguistic and visual forms of representation, the exhibition seems far more interested in reactualisation than the muddied, abstract spaces of virtuality, affect and memory. It tells us History through narrative and by showing evidence flatten as images.

It does so in a way not dissimilar from the encyclopaedia – a format that was very quickly remediated in the digital age with Britannica CD-ROMS and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Holocaust Encyclopaedia online. The MHNT is aesthetically also not entirely unlike Wikipedia, although its curational practices are far more didactic than this participatory platform.

What defines this space as a ‘museum’?

Historically museums have been understood as collections of objects that are usually curated in a way that tells stories about the past. Physicality and materiality have been essential to the very idea of the museum. Here, though, we see only remediations of objects – photographed and/or scanned versions of tangible things. They are represented to us a digital data – file types (such as .pdfs) which we can save in our directories for later reference and where we can rearrange them and catalogue them in relation with different objects than those in the Collection defined by the MHNT.

There is a potential here that is not promoted by the website, but could be incredibly powerful for the continuation of Holocaust memory about the Transylvanian region: the ability for users to curate their own narratives and collections from the sources. The museum’s copyright regulations state that the content can be used for educational and non-profit purposes, but any republication requires permissions. Yet, if a user downloads the remediated objects, they can reorganise them on their private drives. Freed from the physical materiality of the original, these remediated versions are opened up to potentiality – they can now circulate in multiple ways simultaneously. They are no longer fixed only to the narrative in which museum curators have dictated, and yet they are also anchored in a professional, historical space of information.

On first view, the MHNT seems neither very interested in virtuality and affect, nor feels much like a museum. However, a closer interrogation shows that it offers, at times, a specifically digital engagement with the past in which images serve as discrete representations of physical objects, which open up to spaces of potentiality.

Another example of a ‘Virtual Museum’ that offers links to remediated object collections is ‘The Madeleine and Monte Levy Virtual Museum of the Holocaust and the Resistance’ by McMaster University.

VR Tour of Anne Frank’s Hiding Place

Anyone who has been to Amsterdam and thought they could visit Anne Frank’s House on a whim will be aware of the disappointment. This incredibly popular site often has long queues or is fully booked for weeks in advance. Last time I visited, now 10 years ago, I remember feeling claustrophobic not only due to the size of the hiding space but because of the crowds.

The experience of visiting the house in Virtual Reality is incredibly different. You are alone in the space, and even feel slightly disembodied from yourself as you cannot see your hands and legs, and using a Samsung Gear, you must stay stationary, moving only by clicking on prompts. It is worth noting here that an update of the app (which looks more sophisticated than the original) has been released for more advance VR systems – if you’re thinking of getting a Samsung Gear II to see through lockdown, I recommend taking a trip to the new version of the experience (in the trailer below):

Back to the original version on my clunky old Samsung Gear: The ‘tour mode’ of the experience allows you to ‘move’ through the space by clicking on footstep and door icons, which allow you to be transferred to a different spot in a room or into a different room. A short cut to black provides the transition between vector points, once again removing the progressive flow of movement and replacing it with the point-to-point motion of computationally-coded space.

It is also possible to click on certain items to inspect further and ‘speech marks’, which stimulate fragments of the diary which can be heard and appear as quotations written in front of you. I picked up a radio, Anne’s diary, and inspected a piece of wall where her height marks had been drawn.

The Virtual Reality experience disrupts what might otherwise feel simply like a simulation by intercepting it with triggers for user interactivity. Whilst these triggers encourage limited engagement from the user to find pieces of Anne’s diary and to explore the space, they nevertheless encourage an explorative engagement and provoke a sensation of moving between past and present. We do not see Anne and her companions living in the hiding space, rather it is empty. The diary excerpts printed and readout before us add a layer of interpretation over the visual representation, and our motions a layer of action. This is more than either a simulation of the past or the feeling as if we were there at the House as it is as a museum and memorial space today.

At times, the experience can feel quite animated despite the lack of characters represented in our field of view: we might be listening and reading Anne’s very personal reflections, whilst moving an object and contemplating which trigger point to go to next. Whilst some critics might think of this as distraction, Aylish Wood refers to it as distributed attention. We might consider the constant shifting of our focal point an embodied and affective experience in which we become entangled with multiple non-human (such as the drawn image of the diary) and not alive (Anne’s voice represented through the narration) actants, between all of these agentic presences, as the past flitters in and out of the now, potentialities for the future of Holocaust memory emerge.

The VR tour of Anne Frank’s House does not tell the entire story of Anne’s life, the Occupation of the Netherlands, or the Holocaust. It does not offer a sense that we have received a complete, closed story about the past. Instead, by necessitating an explorative engagement from us, it encourages a sense of curiosity. The small fragments I heard and the spaces I saw sparked a desire to find out more: perhaps by reading the diary or finding out what happened to Anne after she left the house and was deported via Westerbork to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. From there, where next might my Holocaust learning journey go? There are, sadly given the enormity of this tragic chapter in history, so many paths it could take. Curiosity and imagination offer a springboard to opening up a multitude of potentialities for new generations to become enfolded into the process of remembering the Holocaust. It is this opening out towards the fields of potentiality, which makes this experience virtual, not simply the technology used to present it.

If you do not have a VR headset, you can also view a 360 experience of the House on Google Arts and Culture.

Some Final Reflections

So-called Virtual Holocaust Museums are perhaps not always museum experiences in any traditional sense. The very physicality and materiality – the aura of ‘authentic’ historical sites and memorial museums, and the material evidence they present is distant from the viewer. Despite attempts to create virtual immersive experiences – these are often far less immersive than the deeply affective environments created in physical exhibition spaces.

Nevertheless, this blog post suggests some preliminary evidence that Massumi’s idea that it is the analogue elements in the digital that bring to the fore virtuality and affective applies to Virtual Holocaust Museums. Yet, I am also curious about the ways vectorial motion and that stilted jagger caused by transitions and images loading after a trigger point is clicked also help draw attention to an inbetweenness – not just between past and present, but between human user and computer. Could this also be understood as opening up potentiality? Whilst the computer’s own code has, in these experiences at least, been defined and is closed (at least until any update), it cannot define what the user does next. How we stimulate visitors or users to continue Holocaust memory relies on how we provoke their imagination and curiosity. How we encourage them to take on the responsibility for remembering themselves.