From Intermediality to Entanglement: New Methods for Studying Digital Holocaust Memory

In November 2020, I presented this argument at a presentation to colleagues at the Smart Family Institute of Communication Studies, Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The talk introduced the new approach I propose for thinking about digital interventions in, and digital futures of, Holocaust memory.

How I got to thinking about Holocaust Memory with Quantum Physics …

And so it began. Now, almost a decade ago, I pursed a masters by distance learning at De Montfort University, where I decided to focus on Holocaust cinema. I continued an interest in the relationship between the screen and the Holocaust through my PhD at Queen Mary, University of London. Having studied and taught film and media for several years, I was struck by how little the majority of writing about Holocaust representation engaged with theories in the very disciplines designed to understand them.

My Problem with the Representation Paradigm

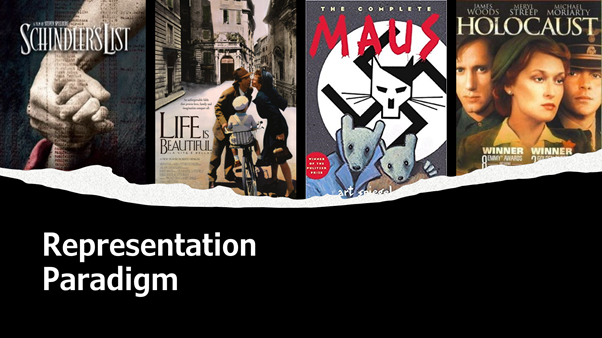

I refer to one particular trend as the Representation Paradigm. This writing about Holocaust media concerns itself with issues of representation and narrative form, but rarely through the critical lens of the related sub-fields of film and media. It is primarily concerned with what we can see (and hear) and how it is told. There are plethora examples of this, and any Holocaust Studies conference will involve animated discussion about whatever is the latest ‘fad’ to disapprove.

Some examples? Elie Wiesel’s now famous lambaste of NBC’s Holocaust in the New York Times, the voluminous critiques of Schindler’s List, which Miriam Hansen felt necessary to defend in her nuanced article ‘Schindler’s List is not Shoah’. Many people were sceptical about the comix form of Maus and its reduction of Nazis and Jews into cats and mice. Then Robert Benigni, famous for his astute political satire across a wide range of themes, was condemed for creating a Holocaust comedy steeped in fairytale references with Life is Beautiful. These are particularly interesting examples as they went on to attain critical acclaim and now form part of the canon on many university courses about Holocaust representation. Holocaust also encouraged much evaluation about Holocaust memory, particularly in Germany; Schindler’s List led to the development of the world’s most comprehensive Holocaust education and memory resource the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive.

The debate about in/appropriateness and un/representability continues to send us round and round and round in circles: someone produces something about the Holocaust in a format deemed to be popular media; academics and others slam it. The storm calms down … until the next release. Few define specific guidelines for what would be deemed appropriate, and positions are often contradictory. For example, whilst fiction is often considered to trivialise, and representations of the crematoria and naked bodies verboten, Son of Saul was surprisingly very well received.

We definitely see the low culture / high culture divide play out in this discourse: Son of Saul was after all far more ‘artsy’ and ‘sophisticated’ as a piece of cinema than a blockbuster, TV melodrama, comix or comedy. When guidelines have been suggested for Holocaust representation, these authors (see Terence des Pres) doubt the actually ability for these to be upheld.

This same rhetoric haunts reception to digital initiatives about the Holocaust too. Some examples of this include the computer game Imagination is the Only Escape. The creator of this game launched an indiegogo campaign to raise funds for its production only to be met with international furore. How DARE someone make a) a fantasy and b) a computer game about this past. It seemed that a new rule had been established: comix were now alright, but computer games verboten.

I have already spoken at length on this blog about this year’s #HolocaustChallenge on TikTok, and Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann and Tom Divon offer an eloquent response to this phenomenon too. Whilst journalists and academics slammed these #POV videos of young people acting as Holocaust victims going to heaven, those of us coming to this debate from a media studies perspective have called for some reflection about format, genre and address in order to understand how these might represent meaningful attempts of young people beginning to engage with this past creatively.

Eva Stories, about which Ebbercht-Hartmann and Lital Henig of the Hebrew University have recently published an article and released a podcast episode. As they describe, there was much hesitation about the use of Instagram for this project and its frivolous likes and emojis, yet the astonishing success of Eva Stories led the Israeli Government to commandeer it as if it was part of the official commemorations for Yom HaShoah. Eva Stories is certainly a turning point for digital Holocaust memory and should make us take popular media far more seriously than we are (because we still are not!).

However, it is not only popular media digital initiatives that are criticised. USC Shoah Foundation’s interactive biography project Dimensions in Testimony has been celebrated in the press for its technological innovations, but heavy questioned in academic circles. Much of this writing, however, focuses on the representational appearance of the project: the projection (wrongly described as a hologram) and the discussion it stimulates with users, rather than the computational logics that distinguish it from previous testimonial texts. Amit Pinchevski has astutely highlighted its database logic, whilst those working in the DiT team have drawn attention to the functionality of its use of natural language processing, and the cultural negotiations at play when teaching machine learning sets (see Traum et al., and forthcoming work by Stephen D. Smith, and Stemaier and Ushakova).

It was with great excitement that I bought Jeffrey Shandler’s monograph Holocaust Memory in the Digital Age upon its release, but I was disappointed to see that the book’s argument barely touches on the digital, indeed he continues to reference his case studies as ‘videotestimonies’, looking through the digital interface, rather than foregrounding its significance.

Beyond the work of colleagues at the Hebrew University, who are producing importance and nuanced media studies analyses of digital Holocaust initiatives, much of the existing and growing literature barely interrogates the specificities of digital technologies, experiences and cultures. It is this issue that has provoked my research, which has arisen from a dissatisfication with the way Holocaust-related media, particularly digital projects, have been understood (or indeed misunderstood). (There are however many promising PhD projects in development – the future is bright!)

Moving beyond representation is particularly significance when talking about digital media, given the increasing analysis of online communication as post-representational.

Circulating the message has become more important than the meaning of the message itself.

Meme culture illustrates this perfectly.

Beyond Representation and the Unrepresentable

My first book on this subject was Cinematic Intermedialities and Contemporary Holocaust Memory. Here, I understood ‘cinematic’ in terms of logics, machines, textures, bodies (human and non-human), and experience. Working critically with Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the assemblage, along with other theorists, notably Didi-Huberman, i looked in-between my chosen screen media’s images, textures and bodies, and the body of the viewer/user and screens, and screen content. Intermediality offered a useful lens for moving beyond representation, but I was not satisfied that this was enough. After all, I was still thinking about Holocaust media and memory in terms of individual texts (my case studies), a particular imagined viewer/user, and a singular experience with them. This does not fully encapsulate our experience(s) with Holocaust memory … there is no one text to rule them all (as if all of our Holocaust knowledge and affective investment in this past is neatly packaged into one film, television series, or digital platform where we can satisfiable get all we need). My experience with each of the case studies in the book undoubtedly affected by experience with the others. The fact I was working in Holocaust education whilst simultaneously teaching and researching film did too. As did my visits to tangible memorial sites.

Digital Holocaust Memory as Remediation … Falling back into the Representational Trap

When I first started attempting a survey of the numerous digital Holocaust initiatives across the world, one thing that struck me was the amount of projects that remediated pre-digital forms, i.e. a tour of the Anne Frank House was transposed into VR, a tour of the physical exhibition of the Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne was simulated as a virtual tour, and Yom HaShoah commemorations in the UK were broadcast in a televisual manner on the web.

There is something interesting to be said about remediation especially given that Holocaust memory developed with and through broadcast media. Yet, to focus solely on this aspect is to look only at the surface of representation again. So, I asked myself what else is there to each of these, and other experiences, and how do they all play a role in a wider Holocaust memoryscape? It was exploring these questions which lead me to the idea of entanglement.

Towards Entanglement

I will start this introduction to entanglement with a lengthy quote from Karen Barad’s brilliant book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Barad’s thorough and amazing piece of writing thinks with Niels Bohr’s psychics-philosophy work to provide an anti-representational model of thinking about matter and meaning, both in her own field of theoretical quantum physics and in cultural theory.

To be entangled is not simply to be intertwined with another, as in the joining of separate entities, but to lack an independent, self-contained existence.

Existence is not an individual affair. Individuals do not preexist their interactions; rather, individuals emerge through and as part of their entangled intra-relating. Which is not to say that emergence happens once and for all, as an event or as a process that takes place according to some external measure of space and of time, but rather that time and space, like matter and meaning, come into existence, are iteratively reconfigured through each intra-action, thereby making it impossible to differentiate in any absolute sense between creation and renewal, beginning and returning, continuity and discontinuity, here and there, past and future.

(Barad 2007, p. ix)

I believe Barad’s work has serious application in the field of memory studies, where it has rarely been explored in depth. The implications of her thinking with and about entanglement suggest a move away from the idea of ethical encounters with the world as between I and an Other, whether human or non-human, towards a complex, ever-emerging space of multiple actants.

It is this notion of entanglement that influences my argument that digital Holocaust memory cannot simply be understood in terms of individual case studies, or specific user experiences, but that we must recognise it as an ever-emerging memoryscape that involves entanglements at multiple levels, which are each continuously entangled with each other.

This approach moves beyond my previous book and its use of assemblage theory, and extends the work of media scholars like Paul Frosh, Silverstone, Deuze, and Couldry and Hepp, who recognise media as integral to our everyday lives and landscapes. Whilst in the Poetics of Digital Media, Frosh talks of ‘mediate and sociable relationships of companionship, or being-with, Barad goes further to suggest the very sense of being, including subjectivity and ethics are co-created as part of a wider entanglement beyond any tangible notion of the self. If existence is not a matter of the individual, but is always co-existence, then we can think about memory production and memory ethics in this way too.

Introducing Levels of Entanglement

So where is this entanglement happening? I’ll end this blog as I concluded my talk at the Hebrew University by introducing some levels of entanglement, but with a caveat that the very notion of entanglement is that the different components at each of these levels are constantly entangling with all the others. Defining these components, however, helps to map the multiple actants that we need to acknowledge in any analysis of digital Holocaust memory in practice.

1. Computational Level

- Blockchain technologies (as being developed by the USC Shoah Foundation to trace reuses, edits and remixes of testimony shared online)

- Neural networks, machine and deep learning

- Lidar and radar scanning (as used by Caroline Sturdy-Colls in her ground-breaking Holocaust archaeology projects at Treblinka, in Alderney (Channel Islands) and elsewhere)

- 3D-image wire-framing

- Bugs

- Programming language

- Code

- Algorithms

- Protocols

- File directories (a computer reads .jpeg as an image, whether this is an image of a shoe, a pot, an instrument of torture, or the emaciated body of a victim, or a corpse)

- Human involvement at the computational level, from programming, training machine learning sets, sharing via the open source culture, to hacking and modding

- Entanglement at the sub-atomic level (quantum computing)

It is particularly significant to be thinking about the computational through entanglement, given the future of computing may well depend on it in quantum computing!

2. At the Interface

- Hardware

- Screens, different types of screens, faulty screens, screens within screens, as the porous meeting point between human and computer: the HCI – Human-computer

- Interface

- Touch and gesture

- Platform

- Software package appearance and interactivity

- Navigation

- The responsiveness of the interface

3. Networked Memory (in the Digital Realm)

- Participatory culture between humans as characteristic of Web 2.0: sharing economy

- Passive participation – algorithmic design to capture and manipulate data without user’s knowledge of what, how much, or what it is used for – surveillance culture (to what extent does Holocaust memory contribute to this? what are the ethical implications of that?)

- Hyperlinks (where do we go .. next? how does what we just viewed reflect on our understanding on the next thing we digest?)

- Tabs (multiple pages, dispersed attention)

- Tagging (telling machines what to relate our content with)

- Bookmarking (curating digital content by tag)

- Portals (like EHRI that bring various other resources together)

- Hashtags

- YouTube’s ‘Up Next’ and other lists created through a negotiation between user input, algorithm, and curation

4. Mixed Reality

At the 2020 Europeana conference, Kevin Kelly from Wired talked about an immersive future he calls The Mirror World, where digital technology would be embedded into all of our experiences with the lived-world. I am really hesitant that the right term here is ‘immersive’, I think the paradigm of mixed reality is a far more nuanced way of understanding this entanglement between physical and digital content experienced simultaneously. In such experiences, the digital alters our experience with the physical, and the physical environment and our user movements shapes any specific digital encounter (and there is much scope to advance how the physical effects the digital here through responsive technologies).

5. The Transnational Multimedia Holocaust Memoryscape

We do not experience digital content in a silo. There is also wider cultural entanglement between:

- institutional Holocaust memory and nonexpert/amateur forms of commemoration and memorialisation

- local and transnational politics from Poland’s ‘Holocaust Law’ to the IHRA (nationalism and national memory do not disappear online!)

- What happens when we click on YouTube’s ‘What Next’ to content not related to the Holocaust immediately after engaging with relevant content?

- What happens in social media comments and the circulation of particular hashtags, for example how Holocaust conversations on Twitter often transform into Israel/Palestine debates, or how the publication of the IHRA’s definition of antisemitism fed into public discussion about the Labour Party in the UK

- how the visibility of online denial and distortion has influenced academics and institutions to campaign against companies like Facebook (as the Claims Conference has done recently) and to produce online content specifically addressing these issues (such as USHMM museum has done); how popular films and viral digital content influences agendas of Holocaust organisations.

- Also, it is important that we recognise that as individuals encounter material that encourages remembrance of the Holocaust, they transform with it, they may influence its reception by others as they share content, they may become more heavily involved in commemorative activities or indeed at the other end of the scale in denial cultures, and with this they transform the memoryscape by enfolding other people into it.

We need to understand ALL of this as an ever-emerging entanglement of human and non-human actants, from the computational level through to the socio-cultural and political. This is the aim of the ambitious Digital Holocaust Memory Project, which is currently seeking funding for time and resources to carry out this comprehensive project.