Interactivity in Holocaust Memory

When digital media was still being called new media, it was often referred to also as interactive media. The suggestion was, even by those critical of this term, that what distinguished this medium from others was its interactivity even if the interactivity was somewhat illusionary.

This of course paved the wave for assertions that pre-digital media was and continues to be passive, whilst digital media introduces radically new ways to turn audiences into active users.

Television and film audiences, newspaper and magazine readers, and museum visitors have always been active in one way or another. Digital media may offer new and different forms of activity, but it also continues and introduces methods of ideological control of audiences too.

We would best think about interactivity via a number of spectra:

- From user agency to creator control (although we should never assume users can have fully independent agency in a way that means creators lose all control and vice versa)

- From cognitive activity to full-body involvement (and vice versa, from simply gestural involvement to bodily engagement which encourages critical thought)

From encounter (dialogue) to a more networked, collective form of participation (although again we must be sceptical of the idea of full participation as a radical democratic notion) - From explicit to passive forms of interactivity

- On a line of responsiveness, i.e. the extent to which a system responds to our input

- And finally on a line of organic to non-organic interactivity, who or what is interacting with what? Interactivity does not always have to include a human

In the Digital Holocaust Memory reading list, you can find a wide range of sources related to interactivity and participatory culture. Rather than repeat how those various ideas speak to the 6 proposed spectra above in this blog, I want to focus on looking at specific examples of interactive Holocaust memory in relation to this model. Interested readers are encouraged to go to the link above to explore various theoretical ideas about these two terms.

In what follows, I do not intend to offer a critique of the content of these experiences, but rather to highlight how they negotiate the 6 spectra of interactivity proposed above.

Journey App

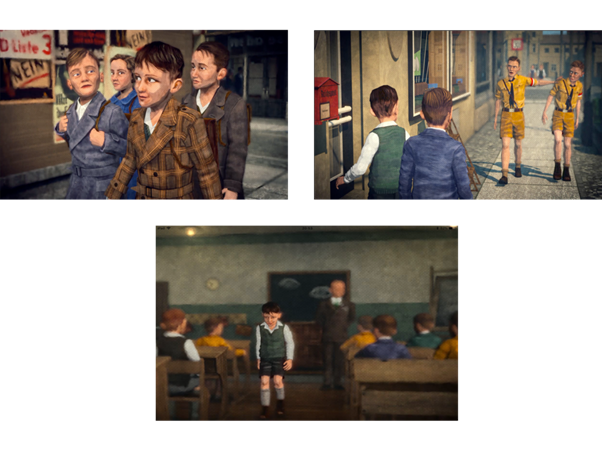

The Journey app is an educational resource created by the National Holocaust Centre, UK. It is designed for primary school pupils and has accompanying teaching and learning resources for use in the classroom.

The app is promoted as an interactive story about Leo – the fictional character, who the Centre also has as the protagonist of its primary school exhibition of the same name (‘Journey’). Leo’s narrative encapsulates many of the key experiences of Jewish people during the early years of Nazi Germany.

The Journey App | Trailer from UK National Holocaust Museum on Vimeo.

The Journey App (Copyright: The National Holocaust Centre)

The narrative is heavily curated and user action is limited in terms of the effect it has on the outcome, i.e. touching the iPad screen enables the user to pick up items which Leo seeks (these items represent everyday life in 1930s Germany with some reference to the specifics of Jewish identity and Nazi ideology) and select dialogue options. Users attract bonuses depending on the number of items they select, which open up further dialogue options at key story points. Users must complete a to-do list of particular activities in order to progress to the next story space.

Each chapter of the story (or level) begins with a cut scene animation, where the user will learn something about the insidious anti-Jewish laws leading to the events of Kristallnacht towards the end of the narrative. The cut scenes are interrupted with moments when the user can choose dialogue options. After this introduction, the user is brought into an explorable space, in which they can look for objects.

The interactivity in the app leans more on the creator-controlled side of the first spectrum rather than user agency, and whilst it involves bodily engagement through the touch screen and through the sense of embodiment created through the first-person POV which allows the user to navigate through the represented spaces, cognitive activity happens more in the extra-diegetic context of the game, i.e. with the complementary learning resources in the classroom. When I find items, I am curious about their significance, but the game world and interface do not in themselves tell me their relevance, or require me to make connections between them.

Classroom use of the app encourages some element of participatory practice, however, this is essentially to teach pupils about a specific historical narrative – forms of anti-Jewish persecution in the early years of Nazi Germany. Pupils are not being asked to participate in the produser sense common to Web 2.0 cultures; they are not being asked to be creators. It may best be understood as at the encounter end of spectra 3, i.e. it is introducing pupils to this particular historical moment.

The interactivity is nevertheless explicit. The story will not move forward without pupil or user interaction through completing the to-do lists and selecting dialogue options. There does not seem to be any forms of passive interactivity, where users are producing content or data to be used by the Centre without their knowledge. At least this is not made explicit in any Terms and Conditions or teacher guide.

There is a basic response system at play here. The program asks users for an input and identifies selected objects that are ‘clickable’ and ones that are not, if the user responses in the desired way then the program responds back through a number of finite options.

There are of course the usual non-organic levels of interactivity at play at the backend as in any digital product, however it is not online. Therefore, once the program is downloaded its interactivity is mostly between user and command system. It does not speak to other machines through protocols and across networks. The Journey app is exemplary of HCI – Human Computer Interactivity at the Interface.

Interactive Biographies

The USC Shoah Foundation have been experimenting with interactive biographies which present survivor testimony to users, who can ask questions of the representation. The National Holocaust Centre, UK has invested in a similar program. However, there are marked differences between the two.

The Dimensions in Testimony project of USC Shoah Foundation has been heavily criticised by those focusing on its appearance, i.e. its visual representational qualities (not surprising given the long running un/representability debates in Holocaust Studies). However, the at the crux of the project is how natural language processing and machine learning can be used to remediate the dialogic encounter with the survivor, after they are no longer with us.

Before the pandemic, the experience was only available at a limited number of sites across the world, mainly in the US, but also in Argentina, Germany and in relation to the Nanjing Massacre in China. However, during the pandemic, the Foundation has made available abbreviated online version of two biographies. My use of one of these is demonstrated in the video below:

With Dimensions in Testimony, there is some element of curation in terms of what testimony is recorded – the survivor cannot ad lib. after the event. Yet, the user has some agency in terms of highlighting their specific interests through the questions they pose.

The program is designed so that responses are selected that correspond as closely as possible to the user’s question (see how my question about whether any of his family were in concentration camps is answered with ‘I was not in any concentration camp’). Yet, the wider program, which uses natural language processing learns from each user input to be more efficient and accurate in its selection of response. Therefore, there is both passive interactivity and explicit interactivity at play here (but passive in a far more productive way that many media scholars see such a phenomenon), increasingly sophisticated responsiveness as the system learns from user input as well as performing a dialogue with anyone one singular user, and non-organic interactivity in the machine learning, as well as that between the user and the computer interface, and a perception of a user to survivor engagement.

The way user input is used to develop the program’s accuracy overtime enables an implicit networked form of participation here, although the user will not be aware of this. For them, it will feel far more like a dialogical encounter. The presentation of the testimony creates the impression or illusion that one is sitting before a Holocaust survivor, although at the same time its resting pose reminds the user that this is a computer interaction too. The user participates in some explicitly bodily action by speaking or typing their questions, however there is also cognitive activity involved in deciding what to ask.

The use of passive interactivity here though does raise questions about the extent to which we need to be transparent with users about how their inputted data is used in heritage, memory and education projects. It is not enough for us to say, ‘ah, but we are using this data for good’. If we want to help young people take responsibility of their data and make informed choices in other spheres, we need to be transparent with them in educational contexts too.

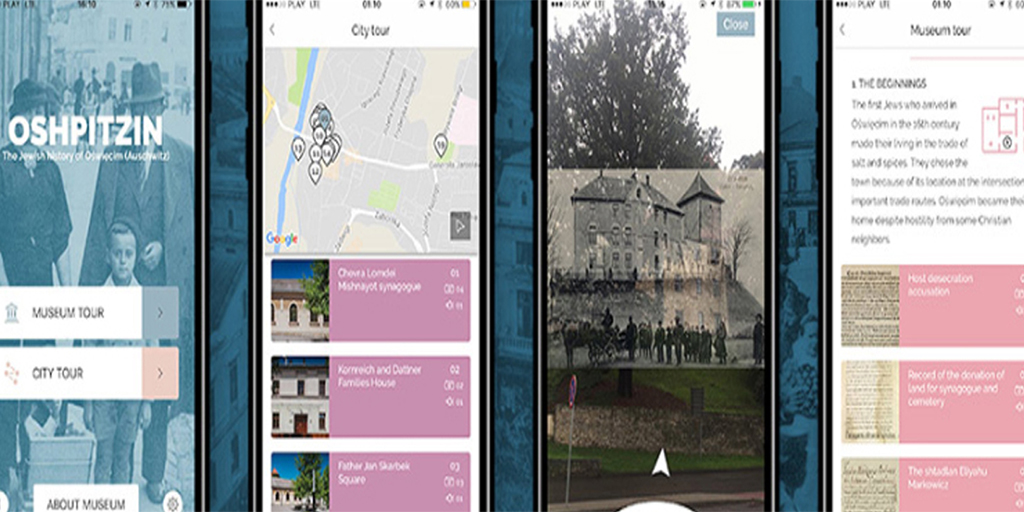

Oshpitizin

The Oshpitzin app created by the Auschwitz Jewish Center in Oşwiécim, Poland, offers a augmented navigational tour around this town, which was the administrative centre of the Auschwitz network of concentration camps. Unlike the camp memorials on the periphary of the town, its centre is rarely visited. You can click on the image below to download the app. Its content is available to view wherever you are, but is best viewed on site in the town (of course when travel restrictions are lifted!).

The app brings together a GPS-enabled map of the town with sites of historical significance identified on it. The user can use the map to create a self-guided tour through the sites, but can also access the content in a list screen.

At each site, the user clicks the site icon to reveal historical narration (available in written and audio forms) and photographs, or in the case of the destroyed synagogue, a 3D model which appears (through the mobile screen) within the actual geographical site at which it once stood. The user can lift their mobile device up to compare the archival images to the contemporary surroundings.

Like the majority of heritage projects, Oshpitzin retains substantial creator control through a finite range of carefully selected and curated material. The limited user’s agency comes in deciding the route of their tour, where to go and what to click on. The dedicated and interested user is of course most likely to look at everything and the app’s content is not overwhelming, therefore this is entirely achievable within a few hours. Nevertheless, the difference between historical and contemporary view leaves a gap which the user must cognitively address thus there is a substantial level of critical agency involved in the experience.

More than the previous two examples, the app requires the user’s full-body engagement. However, as I noted in Cinematic Intermedialities, the bodily movement, particularly the spatialisation of the user within the geographical sites related to the archival images on the screen encourages critical, cognitive interactivity by destablising the idea of ‘place’ as rooted in what we see. By looking at Oşwiécim today (a town with no Jewish residents) and comparing it to the multiculture town it once was, which its Jewish community (c.52% of the population before Nazi occupation) called Oshpitzin in Yiddish, opens up a gap for contemplation, reflection and memory.

Whilst the app can be online, this is purely to support the navigational accuracy, there is no attempt to connect different user experiences into a collective, participatory memory culture through the simultaneous or asynchronous engagement with the app. It is, very much like Journey or how Dimensions in Testimony at least appears to its user, an encounter or dialogue.

The interactivity here is, like the Journey app, explicit. The user is consciously clicking on content. It does not suggest any passive form of interactivity where the user’s contributions add to the development of the app’s content or accuracy. Whilst, like any app it can be altered, it is presented as a finished product and a total experience. The responsiveness of the system is simple, there is not even really the branching choices available at points in the Journey app. If one has dediced to go to a particular site, logic dictates that you will select the icon for that site and read/view the appropriate content.

Whilst Journey foregrounds the interactivity at the interface, with Oshpitzin, the most meaningful interaction comes from the relationality encouraged by the app between archival material, user and place. Thus, the app serves to augment physical landscapes, rather than a contained digital world in itself.

The USHMM’s Kristallnacht Exhibition in Second Life

Once upon a time, museums, schools and universities believed Second Life would be the future of education and heritage. I remember those days well, my own teaching colleagues and I excited talked about creating a virtual classroom. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum was one of many heritage institutions that created exhibitions in the open world space, which is sadly little more than a digital archaeology wasteland now – architecturally still there, but absent of more than a handful of people.

For its time, the Kristallnacht exhibition was pretty forward-thinking though! Once your avatar teleports to the exhibition exterior, you enter a room, where your role as a journalist investigating this historical event is established. You are presented with visual sources and historical narrative on cork boards, and survivor testimony plays in the audio.

By clicking on a glowing book, you open the main exhibition space which provides an immersive walkthrough environment which simulates a historical German street just after the events, but notably without people.

You can watch my walkthrough below, or sign up to Second Life and access the exhibition yourself.

Like many of the examples I have previously introduced, Kristallnacht is heavily curated. The user can move their avatar around the space and select what content with which to interact, but this is limited by what the curators have designated as interactive. Within the navigational environment, only a few things have ‘i’ icons or are glowing to express that they are clickable content. As the player moves their user into particular buildings, they unknowingly stimulate audio testimony and in the atrium, they walk into a space where video testimony plays to them. Testimony is not activated by their choosing.

The experience is not dissimilar from many of the aesthetically historical spaces in Holocaust, and indeed other, museums. We see similiar styles at POLIN and Yad Vashem for example. Cognitive activity mostly equates to listening and consuming pre-curated material in a loose narrative which intends to give the user impressions of the effect of Kristallnacht. However, the experience relies on the user’s micro movements of tapping directional keys or the onscreen arrows with their mouse which simulates full body movement through their avatar. Without the avatar being moved through the space, the user cannot learn anything.

There is an opportunity to contribute to a memory wall in the synagogue and the Second Life environment is a participatory networked space. Indeed, I was actually quite surprised that in my latest visit in the recording above (taken in early 2021), I was accompanied outside the exhibition by another user – other people are still using Second Life! (Although, I wonder if this might be one of the students I introduced to it last week.) However, the exhibition itself does not suggest any particularly collaborative forms of action or memory. Rather, it creates an intimate experience between curated content – the museum voice – and user. This intimacy is emphasised by the human name given to the museum voice through the user who added the content here. Thus, like the other examples above, it feels far more like a dialogical encounter than a networked form of interactivity.

The interactivity is explicit. Nevertheless, as an experience rooted within a free, but still commercial, online space, one might question what Second Life does with any user data. Indeed a 2019 article in Wired accused Second Life of mishandling user data, being hampered by serious security flaws and enabling the simulation of illegal activity.

Auschwitz Twitter Account

In a her PhD thesis and a forthcoming chapter, Imogen Dalziel argues that the Auschwitz State Museum, or more accurately its Press Officer Paweł Sawicki negotiates between an authoritative voice on social media (or what Peter Walsh calls the ‘unassailable voice’), through which he tells a specific historical narrative and dictates how this site should be remembered appropriately, and the type of participatory culture more typical of social media through what Dalziel calls the establishment of a virtual community. Pawel shared his thoughts about digital Holocaust memory with us in an online discussion.

I call upon some of the examples that Dalziel has analysed to consider how the Auschwitz Museum’s Twitter account enables interactivity.

As Dalziel points out, and as I have discussed in a blog post about the controversy surrounding the Amazon series Hunters, the @AuschwitzMemorial Twitter account has had a habit of calling out what it perceives as inappropriate content from popular novels based in Auschwitz, the Amazon series about Jewish Nazi hunters, and young people talking selfies at the site amongst other content. However, it also commends and celebrates users who perform what it designates to be respected behaviour, strengthening a sense of community between these people, who often take it upon themselves to notify the Museum when they too find inappropriate material online.

As Dalziel has argued, some have condemned the Museum’s account for acting like the ‘Auschwitz Police’. Nevertheless, the Museum does not always entirely condemn unofficial memory practices at the site or about the Holocaust in general. As illustrated by the rubber duck incident below, sometimes Paweł seeks to encourage debate amongst the community without judgement from the official account (although other users are not afraid to point out when they disagree with someone’s opinion!). The account’s statement about the controversial TikTok #HolocaustChallenge was also more reserved that some of its previous posts lambasting of popular culture representations of this past.

So in what ways does the account enable interactivity? One cannot escape the fact that on social media, users can comment. Nevertheless, Paweł has created a strong and supportive virtual community, which along with the position often espoused through the account’s posts, encourages a particular interpellation of its subjects regarding how the Holocaust, and Auschwitz specifically, should be remembered. This is an illustrative example of the illusion of interactivity, i.e. that whilst we can feel free to say anything, the dominant ideology of the space often encourages us to align with that discourse. This is of course not a phenomenon exclusive to Holocaust memory.

Despite necessitating gestural touch of a keyboard or a touch-screen, Twitter is foremost a communicative platform, thus it foregrounds cognitive activity. This is particularly emphasised in posts such as the rubber duck one above, in which Paweł specifically invites critical reflection and debate. As a popular account, such posts often attract numerous comments. At this moment, the rubber duck post has 1.7K comments and 887 retweets. The comments respond to each other, provoking debate which is illustrative of participatory culture, yet we should be cautious to how much posting a commenting or responding to another commenter equates to a form of participatory that might be consider radically democratic (in the ways the Internet was perceived as ‘participatory’). It is telling that in the end, the whole conversation provokes the artist to remove their image and apologise, and that the Museum decided to share the apology with its community. Ultimately suggesting a closure to the narrative and thus to the debate.

We kept the author informed about this discussion. The image has already been removed. The apology followed. pic.twitter.com/sZC2UnDbxl— Auschwitz Memorial (@AuschwitzMuseum) November 7, 2019

On one hand, the interactivity is explicit, as users contribute to the debate. On the other hand, users give implicit consent (given that most users do not read the Terms and Conditions in full) for their contributions to feed Twitter’s ranking algorithm so as to improver user experience (but also contribute to the attention economy and arguably encouraging filter bubbles and thus contribute to polarisation in society). Twitter’s Terms and Conditions also give permission for content to be used elsewhere – I can embed tweets into this blog post, researchers can scrape Twitter data to make critical judgements on user behaviour too. Twitter is certainly not as manipulative as organisations like Facebook with its users’ data, preferring an open rather closed approach to sharing data. Nevertheless, users do not always imagine how their data will be used after they originally post it. A fact that was made explicit in the context of Holocaust memory when Breanna Mitchell shared a photograph of her smiling at Auschwitz State Memorial on the site several years ago. Behind the scenes then, artificial intelligence is being responsive to user input in ways designed to adjust the user experience, although in the long-term rather than in the immediate debate.

As an online platform enabling networked communication, Twitter relies on organic to non-organic interactivity at the interface; organic to organic interactivity through the platform; and non-organic to non-organic interactivity through protocols, and communication from machine to machine.

Attendat 1942 Computer Games

This example is the only case study I highlight here that was not created by a Holocaust museum, archive or educational organisation. Attentat 1942 is a computer game available on the Steam distribution platform for PC. Steam has allowed amateur and low-budget games to reach a wide audience by enabling anyone to upload original games or mods to existing products.

The Holocaust is not the main topic of Attendat 1942, rather the user takes on the role of the protagonist who, in the contemporary age, is trying to find out why his Czech grandfather was taken to a concentration camp by the Nazis. SPOILER ALERT: There is a narrative about rescuing a Jewish character.

You start by quizzing your grandmother, then select individuals on a map and chose dialogue options to try to find out what happened to your grandfather. There are mini-games, which serve as historical flashbacks that recall some of your interviewees’ experiences. The mini-games draw attention to some of the absurdities of Nazi ideology and the difficulties of escape, they highlight peril and choices (or indeed seemingly ‘choiceless choices’). They also unlock more opportunities to find out clues about your grandfather’s experience. Towards the end, you are invited to visit an archive and can listen to and see archival content. The story is fictional, but as the end credits of the game reveal, substantial historical research and support from a wide range of institutions informed the game.

When one of the fictional testimonies relates to a specific historical person, place or event, a popup gives you access to an encyclopaedia entry, the entirety of your revealed encyclopaedia can be read via the main menu at any time.

Whilst we might consider Attendat 1942 a closed text like any finished media product presented to its audience, computer games are extensively intertextual and the fan culture around them produces extradiegetic content. For this game, the Steam Community tab includes screenshots of content that has particularly moved certain players, an invitation to speak about your gaming experience on a History YouTube Channel, and walkthrough guides which help others to collect all the games’ achievements, alongside discussions of the different endings and paths through the narrative. Like most games, it is more than a text; it stimulates community.

So, here, on one hand we have curated content and creator control illustrated through the encyclopaedia and the fact the player must learn the game mechanics and a particular attitude and behaviour, IF they want to succeed in their mission. On the other hand, what happens in the narrative is dictated by the choices the player makes and this makes game play different each time (particularly if you failed on previous attempts and therefore have to rethink your strategy). Furthermore, players’ discussion about the game, gaming experience and support documents are shared in a complementary community tab on the Steam Interface, where their contributions extent beyond the limits of the programmed game.

The fictional testimonies are presented as live-action cut scenes, interrupted as with the Journey app with dialogue choice screens. The human likeness of the individuals provokes a sense of immersion, which feels like one is in dialogue with them in a real, embodied space. Nevertheless, our actual bodily movements are gestural – relyin on taps of the mouse or keyboard, but each of these clicks or taps is cognitively instructive, i.e. they reply on us making specific choices. We must listen and observe, then think, if the story is going to move forward.

In game, this is a single player experience and the conversational scenes with the non-player characters certainly makes it feel like a dialogical encounter opposed to a large participatory culture. Nevertheless, the latter is experienced through the extra-diegetic content on the community tab on Steam.

The player’s explicit interactivity happens both within the gameworld, where the computer responses to their actions at the interface in order to define the direction of the branching narrative. Nevertheless, there is potential passive interactivity at play here as well. Steam’s Terms and Conditions clearly outline the data that it collects. Much of this data is useful in improving game play, for example understanding the technical specifications of computers which encounter bugs, some of it helps inform their recommendation algorithm which identifies games it thinks a user will want to buy in the Steam store. Comments and other contributions are also stored, and although there is the opportunity to remove consent, Steam still shares user data with third parties and uses Google Analytics, so we should be aware of the possibility that user’s contributions, which are added to the platform through their free labour creates the richness of its community feel, might be being used for behavioural manipulation elsewhere.

Steam requires users to download games from its servers to their device and enables them to communicate with other users through the community settings. Thus, similarly to Twitter, it requires organic to organic interactivity, organic to non-organic, and non-organic to non-organic.

JoodsMonument

This website is far from the fixed, static idea of ‘monument’ we might be more familiar with in non-digital contexts. Maintained by the Jewish Cultural Quarter in Amsterdam, Joods Monument is a lively, dynamic commemoration space which seeks to paint ‘a multifaceted picture of the history of the Second World War, the Shoah, and the Jewish community in the Netherlands’ by enabling anyone with content to contribute to its every-growing archive presented as a memorial to more than 104,000 Jewish people persecuted and murdered during the Holocaust.

In its most zoomed out view, the site initially appears as what look like tiny pixels, some will be coloured orange, which the monument’s introductory video suggests identifies them as recently visited.

As one zooms in, these pixels become boxes with clearly define names, some of which have images of a person faintly depicted in the background.

By clicking on one of these names, the user can then access the profile page of this victim.

The page includes all information yet gathered about this individual, this may include a photograph, snippets of their life story as gathered from contributors or official archives, a Google map which shows where they once lived and which can be expanded so that the user can see the streetview today. There may also be a list of nearby residents and associated relatives, whose profiles can be explored via links here. The page includes links to associated documents in official archives and a contribute button.

In another area of the site, accessible via the main menu, the user can see recent contributions to the collection and they can register and share content themselves. They can also communicate with other members in the community, which at the date of the YouTube introduction recorded below included 8,500 members who had added more than 80,000 contributions.

Joods Monument can be understood as both a static archive, i.e. a collection of particular sources as available to the user at the moment that they explore it and a dynamic repertoire of collective memory, ever-expanding as users contribute to it. Users may come to this site only to explore the content it already contains, or it might inspire them to carefully go through family documents in order to collate their own contribute. In this latter use case, the user’s agency is more than just contributing to the progression of any narrative maintained within the monument, but becomes part of a collective endeavour to remember this past through the photographs and other sources they transform into publicly available archival material.

The effect of the zoom on the user’s sense of closeness to the victims is a particularly powerful use of technological mechanisms to evoke affect. We start from a position of big data – the statistical (the 6 million in the wider Holocaust context, or here specifically the more than 100,000 Jewish victims) and our zoom action brings us closer to victims until we metaphorically and literally zoom right in (through our decisive click) to a specific individual. For the researcher or browser of the monument, bodily action is otherwise gestural at the interface only, but for the contributor user case, the bodily action extends beyond the engagement with the site as it encourages rummaging through family photo albums or other documents in order to enable particular stories and artifacts to be recorded, preserved and mostly importantly in this context networked with other sources, stories, people and places.

Here then, we also have both the dialogical encounter between researcher/browser and archived content, and the more networked form of participation of the contributors, but also an effort to network the different victims to each other. These are not standalone records of individual, but each page branches out to other residents or relatives whose own experiences connect with this individual. The monument re-creates and re-situates the displaced Jewish community.

Explicit and passive forms of interactivity are still at play in this non-commercial monument. It appears to use a basic recommendation algorithm in order to highlight recently visited profiles on the monument page. This encourages users to repeatedly look at the same individuals as the most recently viewed are highlighted in orange and thus standout from the purple mass of the others. The site informs the user on arrival that it uses cookies. Nevertheless, there are a multitude of explicit ways that the project enables a communal and networked form of interactivity which informs and shapes collective memory.

The use of forms allows for content to be automatically updated by the computer through a responsive system, rather than requiring regular human editorial maintenance. The site warns users that it avoids editing material, but still reserves curational control where it sees fits. Part of this responsibility will no doubt be to check copyright queries regarding uploaded images. Therefore, like many of the online examples discussed in this post, we see the full range of organic/ non-organic relationalities at play in this interactive experience.

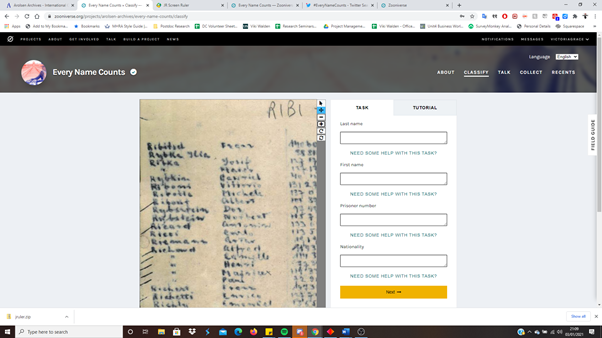

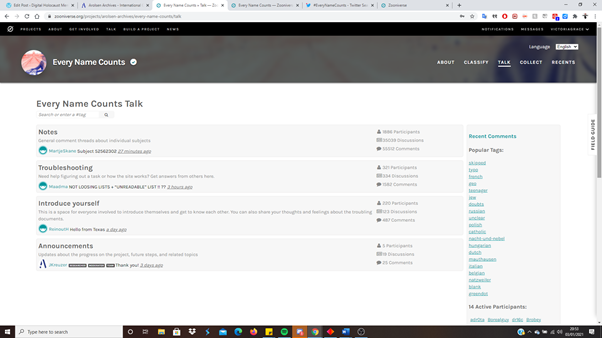

#EveryNameCounts

I now turn to the final example of this post, and this is by no means an exhaustive range of case studies, but rather I hope an illustrative sample of the kinds of interactive experiences being used for Holocaust memory. #EveryNameCounts or #JederNameZählt is an ongoing campaign started by Arolsen Archives in Germany in 2020. A public history project, which makes use of the participatory platform Zooniverse (originally designed for citizen science work, but increasing being used by arts and humanities organisations), is a crowdsourcing campaign to encourage anyone and everyone to help transcribe person data about individuals in the documents the archive holds. The project will help improve the accuracy of the archives’ search, allowing more documents to be tagged to the individuals that they contain.

Between May 2020 and early January 2021, 10,335 volunteers have contributed to the project and it has reached 75% completion towards its initial goal. As well as offering users the opportunity to classify and index documents, the Zooniverse platform has a forum facility where a sense of community can be developed, and users can share queries and support each other. The forum is also used to identify and keep track of #unfinished indexing, where a user may not have been able to fully decipher the content of a document or may have had to stop before they were finished. To increase accuracy, each document is offered to 3 different users and the final results of each classification are then compared. There is also a space where you can create your own collections from the archival material and see those created by others.

There are help documents and a tutorial guide that support new users to developing the rigour and accuracy needed to index the documents, and hashtags such as ‘#notes’ and ‘#typos’ established to bring additional details and issues together. These documents teach users to behave in the same way – as archivists for the Arolsen Archives. If these guidelines were not established, the contributions could be meaningless in their variety. Here, we see negotiation between user agency and creator control at play: users can take responsibility to index documents, but are interpellated by the standards of the institution.

There is minimal use of the user’s full body either as represented through an onscreen avatar (which does not exist on the Zooniverse platform) or in moving through physical spaces themselves here. The majority of their activity involves eye movement, minute gestures at the interface: typing letters, zooming in, and cognitive processing as they must apply the learnt rules of the indexer’s role whilst trying to decipher the digitalised documents.

I commend the dedication of the entire team of Arolsen staff and the Zooniverse volunteers for their attention to detail here. When zoomed in, I struggled still to make out names on the document I was presented. An archivist I will not be!

Whilst, the classify screen may feel like an encounter between archival document and user on the surface, the guidance documents by the Team are always at hand representing the Institutional Voice, and the user is encouraging to use the hashtags which connect this document to collections, and to contribute notes and comments to the talk space.

The ‘talk’ fora are very activate. As of early January 2021, ‘Notes’ has 1,886 participants, 35,040 discussions and 55,154 comments. ‘Troubleshooting’ has 321 participants, 334 discussion and 1,582 comments, ‘Introduce Yourself’ 220 participants, 123 discussions and 487 comments and ‘Announcements’ 5 participants, 19 discussions and 25 comments. It is clear from the large discrepancies between number of discussions and comments that users are not just posting, but are interacting with each other here. This is not a solo experience, but a participatory collective one.

The nature of Zooniverse requires contributors to consent to wide distribution of their contributions, although these can and are often anonymised. Otherwise, their contributions would not aid the research they are designed to support. It is pretty transparent in its Terms and Conditions about how it uses user data to improve and experiment with the site itself, as well as the users’ contributing actively to specific research activities. This is a more passive form of interactivity, although one we have come to expect of all websites these days. Nevertheless, it does not explicate the distribution of data, albeit anonymised, to third parties and uses Amazon Web Services to store is data. Therefore, data that construes a user’s profile through the different types of projects with which they engage, could be shared with organisations beyond those with whom the user intended to interact.

The Zooniverse template has an element of responsiveness to it which the Arolsen Archives team will have been able to adapt to their needs, but which should serve the purpose of easing the process of indexing big data. Nevertheless, they highlight in the introduction to the project that team members will check each set of 3 transcriptions, so human overview is still essential to this work and shapes its approach to accuracy. As a site with uploaded material, live forum discussions, and relying on user input, we once again have the full range of organic to organic (user to user), non-organic to non-organic (protocols and commands between computers, servers etc, and linking content via #hashtags), and organic to non-organic at the interface (between the user and the computer, user and the platform, and the user and the digitised archival documents too).

As we can see from these examples, interactivity persists in a such a wide range of forms, it is almost meaningless to talk of interactivity at all, particularly in terms of thinking about digital media experiences as inherently interactive as if that is an easily definable feature.

In a forthcoming publication, I propose that we replace the idea of interactivity with intra-action, which acknowledges that the most central aspect in collective memory in general, and in Holocaust memory specifically is the relationality between material and non-material things which collaborate in its ever-expanding production. This notion of intra-action comes from Karen Barad’s work on entanglement in science and culture. You can read more about my thoughts on the significance of this to thinking about the future of digital Holocaust memory in another blog post.