Online Holocaust Denial and Distortion

2020 was hailed as a success by many as it appeared major media corporations including Facebook and Twitter were taking action against antisemitism, and Holocaust denial and distortion online. They were responding to increasingly visible protests about their responsibility for content on their platforms.

Nevertheless, I think we must be cautious of celebrating a victory here. Holocaust denial and distortion take many forms, both online and offline. Those that profilerate such content digitally, however, take advantage of the specificities of Web 2.0 cultures. Any attempt to combat Holocaust denial and distortion online must be rooted in a thorough and nuanced understanding of these media cultures.

Responses to Holocaust Denial and Distortion in 2020

YouTube was ahead of the game in 2019, announcing it would ‘ban’ hateful content, including Holocaust denial. This was significant as it was not long ago that a search for ‘Auschwitz’ or ‘The Holocaust’ on the platform would produce denial content posing as documentaries often with titles like the ‘REAL TRUTH about Auschwitz’.

Nevertheless, the content was not really ‘banned’, but rather it could be pushed down to the bottom of searches or made almost unsearchable. The typical user usually only looks only at the first few search results, maybe the rest of page 1 and very occassionally the top of page 2.

A quick search for the ‘Real Truth about Auschwitz’ still produces questionable results, an Israeli documentary exposing a neo-Nazi rock festival in Germany entitled ‘”The Jews are Hiding the Truth” – what the neo Nazis in Germany think’. Whilst the piece intends to be critical of neo-Nazis, it still gives broadcast time to their ideas. Page 1 also notably highlights ‘Jordan Peterson Shares his Thoughts on Hitler’. Whilst Peterson does not deny the Holocaust, he is deeply sympathic to Hitler and seems to justify why he might have desired to kill particular humans as part of a ‘cleanliness’ program. He is a figure widely celebrated by the alt-right.

YouTube has not always removed videos, but rather demonetises them. Even if they do not appear in searches, direct links can be shared via other fora. YouTube thus offers a free space for the uploading and compressing of videos, which can bring in acclaim or profit elsewhere through the embed feature. YouTube’s influence does not stop at its own platform.

However, YouTube’s response spurred further pressure on other platforms, particularly Facebook and Twitter. In 2020, The Claims Conference started their campaign #NoDenyingIt, in which Holocaust survivors directly addressed Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg to encourage him to change Facebook’s stance on Holocaust denial.

More of the campaign videos can be seen here.

The Anti-Defamation League also established a campaign #StopHateForProfit calling on companies to pull their advertising from Facebook. This mirrored an earlier campaign #StopFundingHate, which urged companies not to advertise in newspapers like The Daily Mail, which were printing far-right ideologies.

Facebook’s VP of Content Policy, Monika Bickert wrote a blog post on October 12th, 2020 announcing that the company would be ‘removing’ Holocaust denial content from its website. Including QAnon pages – a web of conspiracy theories with a paedophile blood libel premise at its core, which disturbingly echoes medieval antisemitic ideas.

After Twitter allowed UK Rapper Wiley to espouse a stream of antisemitic rants for an entire weekend in July 2020, including incitements of violence against Jews, the platform was pressurised to also change its stance. Twiter banned Wiley, who was still able to share posts elsewhere and apparently created another account on the platform too (although I have not been able to verify this). Amidst fears of disinformation with the upcoming US Presidential Election and the ongoing Covid19 Pandemic, Twitter also followed YouTube by including a ‘fact checking’ mechanism which would present posts with a warning that the content is not verifiable.

The Wiley case led to a campaign #NoSafeSpaceforJewHate and a social media blackout supported by politicians, Jewish users, Holocaust organisations, and other human rights and genocide memory groups, including Remembering Srebrenica in the UK. Supporters of the 48hr blackout pre-empted it with a statement that they were taking part and were then silent for that period.

In solidarity with the Jewish Community and to protest anti-semitism, our Twitter account will be off for the next 48 hours. #NoSafeSpaceForJewHate pic.twitter.com/75Z0qazKRz

– Remembering Srebrenica (@SrebrenicaUK) July 27, 2020

These popular social media platforms have struggled to negotiate their libertarian ideals of ‘free speech’ and the role they play in the spread of dis/misinformation, which includes, but is not restricted to, Holocaust denial and distortion.

Stephen D. Smith, Executive Director of the USC Shoah Foundation recognises that this is just the beginning of any fight against online Holocaust denial and distortion, yet I am more hesitant than him that banning is enough. Smith argues:

Yes, blocking abusers works; they don’t just sprout up elsewhere.

Yet, media theory suggests otherwise. In the rest of this blog post I introduce some of they fundamentals about digital media cultures to highlight that any attempt to combat Holocaust denial and distortion online, if indeed this is even possible, must start from a position that acknowledges that many of its attributes are fundamental to Web 2.0 culture and that some of the tactics currently used to counter it may indeed further perpetuate such behaviour rather than suppress it.

Framing Holocaust Denial and Distortion through Digital Media Theory

Current actions against denial and distortion tend to do one of the following:

- Provide fact-checking (i.e. if you mention the ‘Holocaust’, your YouTube video will be accompanied with a link to the Wikipedia page for ‘the Holocaust’).

- Ban users or groups.

- When media companies do not listen, activists target advertisers to pressurise them to withdraw these revenue streams for the media conglomerates.

Let us address each of these in turn.

Fact-Checking

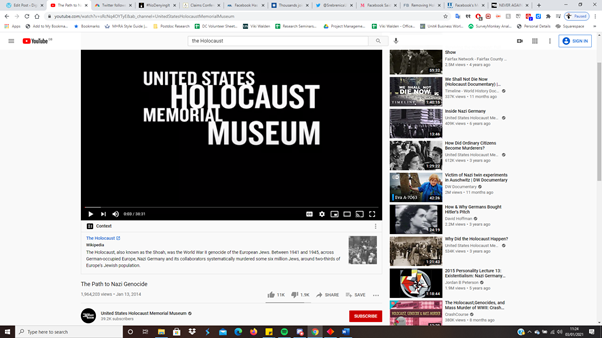

If I look at a YouTube video posted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (the USHMM), it is accompanied by the Wikipedia page for ‘the Holocaust’.

Yet, if I search for ‘Holohoax’, I come across an interview with internationally renown Holocaust denier David Irving, in which he discusses his book about Himmler and says ‘he established the Holocaust – whatever that was’ and the video is not accompanied by the Wikipedia ‘the Holocaust’ page.

Here, YouTube fact checks one of the most established Holocaust museums in the world, but not one of the most famous Holocaust deniers. Why? We should not be so quick to assume this is a deliberate attempt to promote denial. Rather, we must understand it in terms of platform capitalism as a cultural system and the technicalities of how these sites function.

Firstly, it may seem peculiar that YouTube decides to fact check an established research, museum and educational organisation with Wikipedia. However, Wikipedia is the font of libertarian internet ideals – arguably one of the few exemplary cases of it working as planned. The digital uptopians who wrote for Mondo 2000 and Wired, and established Silicon Valley and the dot.com era genuinely believed the Internet would offer a new form of democracy, which would disrupt established power hierarchies. Museums, and other ‘experts’, represent the old order – the voices of authority educating the people. The Internet would highlight the power of what Pierre Levy called collective intelligence – multiple voices coming together to think and develop ideas collaboratively. The many is better than the one (in this line of argument). Offering Wikipedia as a source opposed to educational or research websites enables platforms such as YouTube to still foreground their libertarian ideology and promote grassroots, open source content created ‘by the people’ as fact even though the site can be changed at any time (although the Wikipedia community is now pretty good at correcting accuracies). The idea of post-truth has not emerged with the far-right and politicians like Trump, it has grown out of the collective construction of knowledge online, which can be constantly disputed, negotiated and edited. The very action of placing Wikipedia as the authority source questions the expertise of Holocaust organisations. These libertarians value the collective over the single source, the authority or expertise of the latter is irrelevant.

Secondly, we must not begin to think YouTube is deliberately promoting deniers like Irving. Instead, we must accept that deniers have become better at navigating their relationship with algorithms than Holocaust organisations. The latter often treat platforms like YouTube as broadcast media, similar to television rather than understanding their digital specificities. In a forthcoming article Tomasz Lysak writes about the need to read the code of YouTube videos as well as the content, when studying how they are used for Holocaust memory. Let us compare the two pages: The USHMM video and Irving interview.

USHMM: Holocaust is in the link name of the video, in the user name and in the name of the file because it contains the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. It is also mentioned in the description of the video. There are also a limited number of tags in the metadata and ‘Holocaust’ comes first:

<meta name=”keywords” content=”The Holocaust (Disaster), Germany (Country), Nazism”>

<meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”The Holocaust (Disaster)”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Germany (Country)”>

On the Irving interview page. It is notable that it is not posted by him (if he has a YouTube ban, this is a good way around it). I searched for ‘Holohoax’ and his name came up, which suggests a relational algorithm has connected the two. Any term previously related to ‘Holohoax’ will now show in a search for the term, even if YouTube claim to be deleting obvious denial content (notably none of the videos that appeared in the search had ‘Holohoax’ in the title or description).

Like the USHMM video, it contains the word Holocaust in both the metadata and the description, but NOT in the title of the video or the user name. This may suggest that YouTube’s fact check is only being used at the top level and not responding to videos which include ‘Holocaust’ in the description or tag. However, the video also uses a number of tags, ‘Holocaust’ is not prioritised here in the same way it is by the USHMM video.

<meta name=”keywords” content=”David, Irving, Nazi, Heinrich, Himmler, Shoah, Holocaust, Germany, history, WW2, Albert, Speer”>

<meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”David”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Irving”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Nazi”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Heinrich”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Himmler”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Shoah”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Holocaust”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Germany”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”history”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”WW2″><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Albert”><meta property=”og:video:tag” content=”Speer”>

This echoes my experience of setting up the Digital Holocaust Memory social media profiles, as discussed in one of my first blog posts. On Facebook, particularly, I had problems using the word ‘Holocaust’ in the name of the project’s identity – it was a forbidden word. Yet my content was not malicious, I was creating a page dedicated to promoting Holocaust research!

Fact-checking on social media might actually be hampering Holocaust education and research on these platforms, rather than successfully suppressing denial. If one removes any reference to ‘the Holocaust’ in the description, tags or title, you are unlikely to have a fact checking mechanism complement your video. You could still therefore distribute denial or distortion on YouTube and encourage viewership in two ways:

- Share the link directly via other fora

- Use a term not yet detected by these platforms as related to antisemitism and denial, i.e. ‘play the system’.

Media education scholar David Buckingham has highlighted the problem with fact-checking mechanisms as ways of combating misinformation, disinformation and fake news. In his The Media Manifesto. He argues instead for critical media studies to be at the fore of educational agendas, so learners can be equipped with the skills to assess all news sources. Fact-checking gives media corporations the authority to decided which content needs to be checked and which not, and to choose which sources are correct for the facts.

Banning Users

You cannot ban a user from the Internet. The sensation of control that comes with suspending an account is mythical. Web 2.0 is a gaming culture. Platform capitalism is gamified. We seek the most likes, the most comments, to be voted up, and to have our content shared. When users or groups are banned, part of the game is figuring out how to retain visibility. It is like trying to navigate away from the boss in a Dungeon Game, whilst you’re trying to restore health points. You need to be out or range or use an invisibility skill for a bit before reappearing, fully ready for the attack.

Symbols such as ((( ))) were used to identify Jewish individuals for doxxing by the alt-right. The use of ((( ))) was in itself meaningless, it could just as well have been ** ** &£)% £)%)&$, but as with all signifiers, it has been given cultural meaning within a specific group. It is a code that only they can decode. It is notable to recognise however that once others worked out this coding, ((( ))) began to be used as a tool of resistance with people using it to proudly mark their Jewish identity and thus rendering its power irrelevant.

When Cloudflare announced it would finally stop supporting 8Chan, the platform quickly reappeared as 8kun. Censorship is like death in computer game logics – you can respawn again and will need to adjust your strategy.

Such gaming tactics are designed to get around censorship, but they are not only used by the far-right, and deniers. More liberal users such as @Whatswrongwithmollymargaret on Instagram have changed symbols in their posts in order to promote women’s sexual health, when images of breasts and words used to describe female genitalia are considered ‘bad taste’.

Banning users is like delivering attack points in a computer game, but it is not going to remove the user, the groups or the ideologies. The more we push Holocaust denial and distortion to the peripheries of the Dark net, 8kun, 4Chan and specific forums, the less we will be ready to expect what might come. That is not to say that we should encourage it on mainstream platforms, but that simply banning it can just assist in playing the game and can make playing the game more desirable.

Targeting Advertisers

This may work better for newspapers than social media platforms. Although, I still have doubts about the former. It is great for raising the awareness of companies like Lego (who see themselves as celebrating diversity and liberal ideas) that advertising in the Daily Mail may not align with their brand identity. However, if anything this helps the brand’s profitability rather than attacking the cause of hate. The Daily Mail will be able to find enough corporations that support its intentions and Lego or any other company who was advertising here can not feel good about themselves for retracting. As such, it supports neoliberal capitalism, a system which promotes global inequalities and relies on the exploitation of others.

I am even more sceptical that targeting advertisers does much damage to the social media platforms that enable the proliferation of hate. Whilst it may appear on the surface that they rely on advertising revenue because we constantly see recommended products and sponsored posts. This is very much the surface of the extensive profit they make off data.

They may allow advertisers to target you based on your user data, but these media corporations also share data with agreed partners – they make money from selling data and manipulating user data and behaviour. They rely on what Christian Fuchs has called user’s free labour to make their profit.

The attention economy is central to the way social media platforms work. They need to keep you on the platform for as long as possible. The more sensationalist or negative the content you see is, the more likely you are to comment on it and share it. Your explicit user interactivity feeds into what Marc Andrejevic calls passive interactivity which benefits the social media corporations.

What Next?

To tackle Holocaust denial and distortion online, we need to understand that many of the mechanisms that enable it to gain visibility and traction are absolutely fundamental to platform capitalism:

- Libertarian ideals about the Internet, free speech and democracy push Wikipedia up as a reputable fact-checking source over expert organisations. Silicon Valley supports the radical over the expert.

- Current algorithms designed to address Holocaust denial and distortion seem to targetonly specific levels of content in the code, not all of it. You need to be able to play the game to be the most visible or to avoid censors. Is it enough to depend on basic code to source and effect the visiblity of denial and distortion.

- The Internet is fundamentally a gaming culture.

- Social media use our labour for profit, they rely on shareability. The meaning and substance of content is less important than the probability that it will be circulated. We know from established and recent research into news values that sensational and bad news get shared most frequently (along with ‘cute’ content). Shareability relies on the way the content is structured: its use of images or videos; its snackabilty in length; and the wording of its headline – does it encourage curiosity and outrage?

However, whilst some of the blame must absolutely lie at the door of social media corporations, we must not forget that their content is created by users, and it is other users who decide whether to comment, like or upvote others’ posts. We must understand the circulation of Holocaust denial and distortion as a wider phenomenon within neo-liberal and platform capitalism. We need to interrogate and change the culture at large if we want to tackle it.