Playing Memories? Digital Games as Memory Media

In our second guest blog, Tabea Widmann from the University of Konstanz discusses the potential of computer games for Holocaust memory.

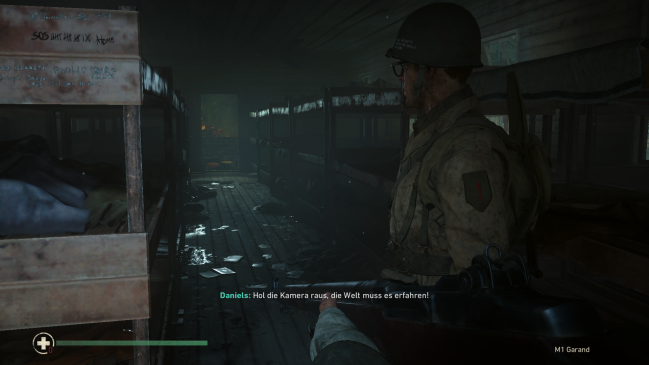

Take out your camera. The world’s gotta know.

Uttered, with the shock of complete disbelief still mingling in his voice, Private Daniels asks this of his fellow squad member and war photographer Stiles upon finding a deserted Nazi forced labour camp.

Admittedly, it is a virtual camp, found by virtual US American soldiers in a digital game about World War II. Yet this request, expressed by the player’s own avatar, that she takes over in Call of Duty World War II (Sledgehammer Games, 2017) (CoDWWII), is given a very central position within the gameplay: not only can the player witness Stiles taking out the camera and promptly documenting the encountered horrors. But moreover, the taken pictures are displayed full screen for a few seconds immediately afterwards. They cannot be closed nor clicked away.

Impressions from the discovered barracks in the Mission “Finding Zussman” in Call of Duty World War II. Stills from own gameplay.

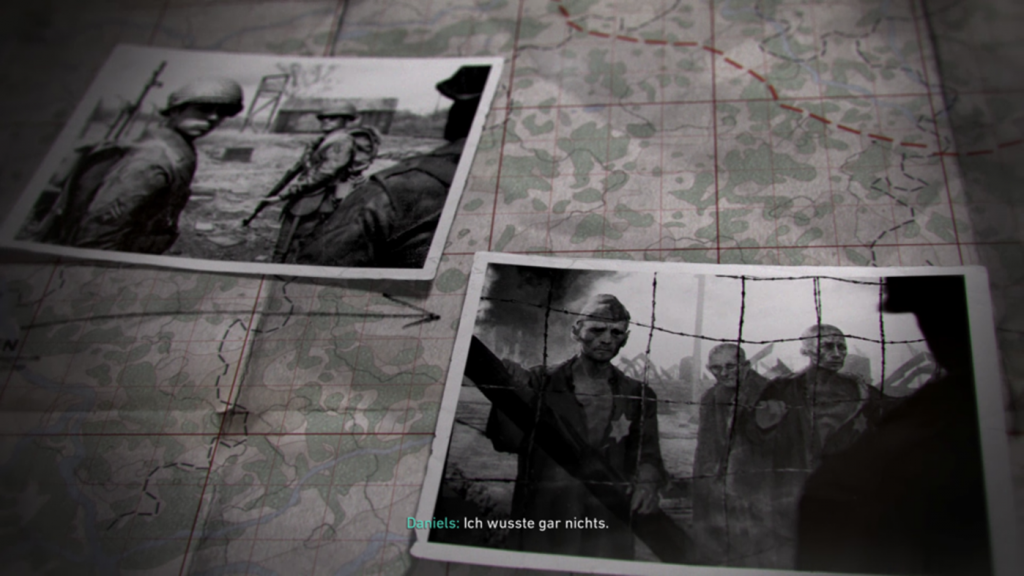

The player has to endure to look at them and, given she has come in touch with the mediated memory sphere that popular culture has created about the Holocaust, she can recognise them as remediations of motives all too well known: documentations by the Allies upon finding the concentration and labour camps of the Nazis; first shared and reproduced in photographs, newspapers or documentaries, now repeatedly remediated by a myriad of Hollywood productions, series, video channels as well as privately reproduced and displayed on people’s social media accounts.

CoDWWII, and digital games in general, offer a very special experience of encounters with this past:

- it is the player’s avatar that gives the order to document the discovered horrors. Rune Klevjer argues that as an “avatarial prosthesis” the avatar is ascribed an ambivalent character: On the one hand, it is used, serving as the player’s instrument to interact with the game elements. But on the other hand, it also expresses the player’s incorporation within the game structures, thus serving as a temporary expression of her playful being. The impulse to remember comes, consequently, from the one game element with which the player identifies the most, whose values she has been encouraged to share, whose story, perspective and feelings have become most familiar.

- the player is thrown into a situation of double-recognition: She can explore the implicit references that the game world-construction of “Stammlager Berga” offers towards the globally accessible network of the digital memory sphere concerning the Holocaust; the gate with barbed wire, the barracks, flocks of ash in the air, the mutilated bodies of the dead, the melancholic music with the violin as lead instrument, to name but the most dominant. She is also forced to recognise Stiles’ photographs as true representations of the space that she is momentarily experiencing within the game. The player functions explicitly as a secondary witness in the way the memory scholar Aleida Assmann has defined it. The player experiences the gameworld as well as the taken photographs. Thereby, she can verify the accuracy that links motif and medium. This assuring position is promoted for the whole game experience:

Different from watching a movie, the experience of playing a digital game is dominated by the impression of active participation. The player perceives herself as being immediately as well as diversely involved in the emergence of the game’s story. That is also true for the discovery of the camp in CoDWWII: The player can move around freely in the constructed space, looking at what she chooses to, experiencing the space in her own pace and order. It goes without saying that the freedom of these movements is always determined by the rules and regulations of the game – thence, the ludologist Jesper Juul, defines the latter as a primarily rule-based experience. Yet, the immersive qualities of digital games can successfully belie its rigorous limitations of player-actions. Consequently, the player can perceive herself as the empowered entity.

With this involved as well as involving player position, the game offers a persuasive substitute version of a past that is otherwise always beyond the reach of immediate experience. It creates a moment where the advertising promise “how it really was” appears finally fully accessible – or does it?

Playing and Witnessing

Even when digital games do not position themselves as explicitly reflexive towards the mediated memory sphere that surrounds the Holocaust, the latter has indeed become a part of their topics, their game worlds. The question whether it is “barbaric to design video games after Auschwitz” as Gonzalo Frasca subtitled his essay “Ephemeral games” does not apply to current developments anymore: Digital games have already started to participate in the multimedial memory network that surrounds the Holocaust, drawing on long established memory narratives, iconography and symbols of the “mediated memory”. Rather as more and more memory scholars, among them the German historian Wulf Kansteiner, demand, it is of utmost importance to overcome a “gaming taboo” of the Holocaust.

The quality I seek to stress is the paradigmatic parallel that opens up between game acts and acts of witnessing:

They both imply an ambivalent position of distance and involvement with a situation wherein one’s own role is defined by seeing or hearing something, attesting to its truthfulness through one’s presence; be it to legitimise another person’s account of a past or concerning the events themselves.

Game worlds are constructed as negotiable places that invite us to explore them, to move within them. Such movements are induced via changes in what the player sees, hears, perceives. These changes, at the same time, follow the player’s own decisions, creating the impression that her presence is a necessary imperative. Because without her being there, creating and simultaneously witnessing the changes in the game world, the emergent story would be irrelevant. The same is true to the relation of witnesses and the past: we cannot remember a past of which we, as the later generations, have no notion.

Dependent on the accounts of witnesses, personified in survivors but also in memory objects, such as photographs, documents and film material, their reading of the past shapes how we think about it, how we communicate it and, ultimately, how we ourselves will continue to pass it on to future generations.

As memory media, digital games influence the ascribed position of a player as a witness of the presented past in two aspects: On the one hand, the aesthetics of the game world – perceived here as what the media scholar Henry Jenkins describes as spaces of “narrative architecture” – can evoke memory tropes; recreating what Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann has termed cinematic memory “super signs”, such as the camps, the yellow star or the uniform of the SS perpetrators.

The intro of “Finding Zussman” uses simulations of photographs which again remediate iconic representations of pictures of atrocity, e.g. the perspective through the barbed wire, the shaved, malnourished survivors, the striped clothing with the yellow star. Still from own gameplay.

But on the other hand, and more importantly, the game system influences how the player gets into contact with these tropes, narrative and images as well as – in the context of Holocaust memory most importantly – what is considered a moral or an immoral action within the game. Herein lies, in my opinion, the strength of digital games as memory media: In their “half-real”-quality, as Jasper Juul ascribes to them, the roles emerging from the games’ narratives and atmospheres become reconnected with the memory sphere: Their constant negotiation of “becoming” within the game double-layered gets entangled with the player’s “becoming” within the digital memory sphere. This role is equally shaped through the definite, medium-specifically shaped possibilities of (inter-)action of a user as well as the prescripted, recognisable acts of a witness; the act of playing, therefore, becomes an act of witnessing.

In her concept of memories that derive from a mass mediated experience with past narratives, Alison Landsberg draws on the term “prosthetic”: Like a physical prosthesis, these memories are not naturally obtained. Rather, they are a result of a pre-shaped mediated experience with the past. They are sensuous none the less, as they become part of the receiver’s identity while simultaneously remaining interchangeable and most of all useful. Landsberg argues finally that these prosthetic memories “help to condition how an individual thinks about the world”. This prosthetic quality can also be ascribed to the acts of witnessing in digital games: The role as a “prosthetic witness” is constructed medially, thus it is obtained temporally and locally distanced from the witnessed events. Additionally, as a “post”-experience it is carried by the player’s imagination. Finally, this attribution is dependent on its recontextualisation with other memory experiences that the player has obtained or is yet to gain within the digital memory sphere.

At the same time, “prosthetic” wants to stress the ambivalence, even the mistrust, that such a contact with the Holocaust might create: It is the already established narratives and iconography that are most of all passed on, the established (re-)mediation of the events and not the painful past itself. Consequently, the reassurance of a digital game that the offered experience is an authentic one, is dangerously wrong. Digital games, namely, always consist of presently created worlds that can help us to understand what narratives and images are still connected to a certain past, how it is perceived, what relation is implicitly constructed in the present and how the player is allowed to interact with it. The same is true for all memory media: They never really show the past.

Which Digital Games Are Out There?

In many people’s minds, digital games are still perceived as a major medium for neo-fascist groups. Games such as KZ Manager, an economic simulation where the player has to manage their resources to keep the concentration camp “going” and where the murder of prisoners in the gas chambers becomes a pseudo-rational business decision, have emerged periodically in different versions on various platforms.

Yet, it seems dangerously linear to connect the possibility to play within Holocaust representations directly with neo-fascist tendencies. As the Digital Terrorism and Hate Report (DTaHR) of the Simon Wiesenthal Center shows, extremist groups do profit from the possibility of the digital sphere to connect and create the feeling of participation in an “invisible mediated mass”, as Shinichi Furuya expresses it in his discussion of Elias Canetti’s “Crowds and Power” in the context of digital mass media. Through the latter, such a feeling might be more easily maintained, even though the group members are physically distant from each other. And the act of playing might satisfy the need for group activity and thus result in group identity becoming strongerthan mere communication or exchange could. Yet, as the DTaHR also exemplifies, such a substitute enactment of group identity can also emerge from playing games that are not directly connected to the Holocaust – as was the case with Clash of Clans (Supercell, 2012). Here, the game became a possibility to enact a radical collective identity because a group recontextualised it as such, e.g. by naming a Clan “BadNewsForJews”. Thereby, the game setting and the game acts were layered with the group’s ideology that again emerged from a common interpretation of the Nazi past.

If games could help these groups develop stronger identities, might they also offer possibilities in helping us to build cohesive memory groups to perpetuate rather than resist Holocaust memory also?

At the same time, the thematic introduction of the Holocaust into actually unrelated digital games through MOD’s is also a recurring phenomenon. Such a process is shown in the game Don’t starve in the Holocaust, a MOD by Guy Ulmer, presented in its first fragmented structures developed at the Global Game Jam 2014 at Tel Aviv. It is a MOD of the Canadian indie survival game Don’t starve (Klei Entertainment, 2013) and is a perfect example of the democratising power that Jenkins ascribes to the convergence culture, the meeting (or rather melting) point of “bottom-up consumer-driven” actions with “top-bottom corporate-driven process[es]”. The game principle of Don’t starve, where malnutrition and mismanagement can lead to hallucinations, changing the game world into a disturbing sphere, is reversed in this MOD.

Here, survival is possible when the avatar enters into a dream-like perception of its surroundings, since it is more bearable than the horrifying game reality. In this MOD, the offered game structures were reintroduced in a memory cultural context.

Game still of Don’t starve in the Holocaust. Source: https://globalgamejam.org/2014/games/dont-starve-holocaust [07.09.20]

These circumstances get even blurrier when the recognisable memory expressions are embedded in a fantastic or counterfactual game setting, such as in the Wolfenstein series or Darkest of Days (8monkey Labs, 2009). In such games, the possibility, as Kansteiner argues, to “radically rewrit[e] and reinvent[…]” the past “every time we turn on our computers” is enhanced since fantasy and history can be interwoven almost arbitrarily. Darkest of Days, for example, conjures up a concentration camp as one of the darkest scenarios of human kind. Its experience is framed by battles during the American civil war or, making the mixture of playable scenarios even more absurd, a mission during the eruption of Vesuvius in ancient Pompeii.

Still from a walkthrough of the mission in the concentration camp of Darkest of Days. Source: k0noa. “Darkest of Days part 14: Nazi Camps”. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAptkaOZKOQ[05.09.20]

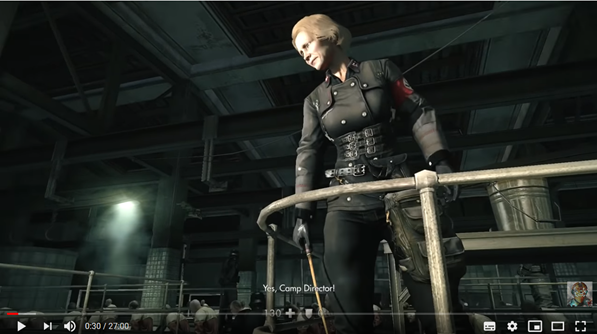

This is, for example, the case in the mission “Camp Belica” of the game Wolfenstein: The New Order (MachineGames, 2014) where the avatar, Captain William Blazkowicz, voluntarily enters said camp on a rescue mission. There, he witnesses a selection process, gets forcefully tattooed and is assigned to a working unit. The game does not hesitate to throw the player into the position of a (voluntary) victim; a position that is, in spite of the counterfactual narrative setting, constructed around the narratives of survivors.

Not only does it offer thereby a very dubious pseudo-experience of an arriving camp prisoner, but since Blazkowicz naturally escapes some minutes later, the game actually negates the strongest attributes of the prisoners; namely, the feeling of passivity, paralysis even, of being at the mercy of torturously arbitrary rules within an “order of terror”, as the sociologist Wolfgang Sofsky described the structures of concentration camps.

Additionally, this setting is accompanied by reappearing elements of “Nazisploitation”, such as the stereotypical Nazi femme fatale Frau Engel (which translates ironically into “Mrs Angel”) or the hyper-technical power of Nazi-robots; the latter makes up, together with the repeatedly reappearing Nazi zombie, a popular genre of its own.

“Frau Engel” in Camp Belica. Still from a walkthrough of the mission “Camp Belica” in Wolfenstein The New Order. Source: theRadBrad: “Wolfenstein The New Order Gameplay Walkthrough Part 11 – Camp Belica (PS4)”. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWxbON_ngVQ [05.09.20]

Could such moments of disruption encourage a renewed interest in an animate memory culture more efficiently?

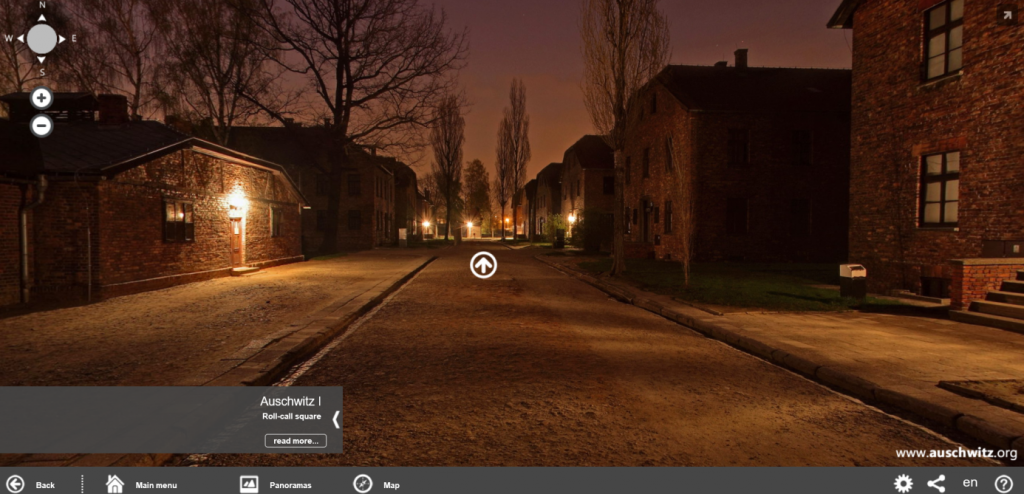

Still, the gaming sector and the memory sphere have become increasingly aware of each other. Returning to Cod WWII, its self-reflection as a memory medium is exemplary shown in the additional regulations within the camp: The avatar cannot use his gun, cannot run or jump. The player can only walk and look around, taking in the traces of the unspeakable suffering that occurred in this place. Thus, the experience is aesthetically very close to virtual tours of memory sites (we have mentioned tours of Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Bergen-Belsen in previous blog posts).

Screenshot from the virtual tour “Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau”. Here, the users can experience impressions from the site online through various 360-degree images. These are connected through arrow symbols, thusly creating the impression for the users to be moving on the site. Moreover, there are additional info boxes with background information to the specific space. Accessed via http://panorama.auschwitz.org/tour1,en.html [07.09.20]

In the final scene of My Memory of Us, the player, via the avatar of the granddaughter, reunites the two parts of a photography. Thereby, the old owner of a book store and her grandmother recognize each other as the boy and the girl which were the lead avatars throughout the internal game plot. Stills from own gameplay.

A game that allows the player to fail “finally” is the German strategy game Through the Darkest of Times (Paintbucket Games, 2020). Here, the player navigates the different members of a resistance group on a map of Berlin, planning different actions of resistance, tactically manoeuvring the group members. Simultaneously, the group is always threatened with its termination, either due to imprisonment of its members, their death, or their decision to quit out of fear of the first two options.

If the group’s morale is completely shattered, it dissolves and the game ends. But even here, the defeat is interpreted as a victory since the player’s engagement is acknowledged as successful, appreciated actions of resistance. The game even honours the player’s efforts with a virtual memorial of the own resistance group.

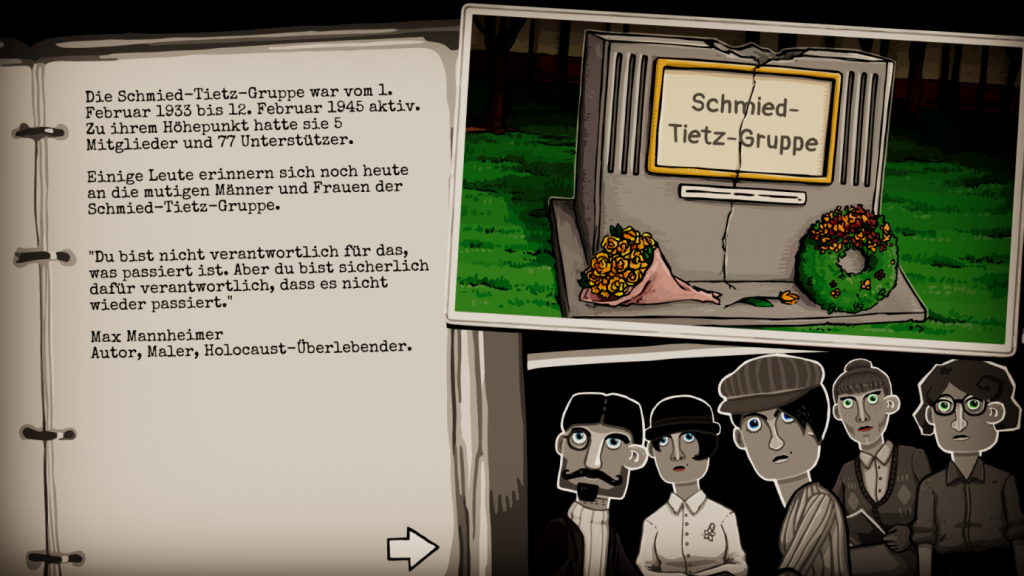

The text summarizes the player’s achievements as the coordinator of the resistance group in Through the Darkest of Times. The second paragraph, for example, translates into: “Some people still remember the courageous men and women of the Schmied-Tietz-Group”. Still from own gameplay.

These analyses raise an important question: how can we compromise between the multiple, tragic and complex narratives of the Holocaust, often perceived as ‘unimaginable’, and the drive-in computer game design for a satisfying narrative ending?

For my last aspect, I want to return to Klevjer’s argument about the prosthetic relationship between player and avatar that shimmers between subject-embodiment and instrument-object. Approached as an act of witnessing, this relationship can also be perceived as a shimmering between generations. While the avatar is part of the historically set game world, the player is a member of a generation born after the Holocaust. Thus, the witnessing experience within as well as from the game is connected to a (simulated) transgenerational transfer where the player’s position is fluid and changeable, shifting between immediate and hypermediate moments. It is here that I personally see the biggest chance for the institutionalised prerogative of “never again!” to be integrated successfully into digital games as memory media.

The serious point-and-click game Attentat 1942 (Charles Games, 2017) can serve as an example of this development where the player explicitly participates in transgenerational negotiations. From the perspective of a survivor’s grandchild, the player tries to find out why her grandfather was arrested and deported into a concentration camp. Since he himself is at the hospital, the player has to discover new sources, from the grandmother, neighbours, old acquaintances as well as photographs or the grandfather’s diary to answer this question. The gaining of memories is paralleled with the gaining of coins that, in turn, can be used tactically in the game, e.g. to repeat an interview. Thus, the game system promotes the active involvement with the past because gaining knowledge about it is the central objective. The player witnesses the consequences of her game actions, her multiple involvements while not only experiencing simulated situations of her grandparents’ past but most of all the perspective of an after-born generation.

On the one hand, the missions in Attentat 1942 as the grandchild are aesthetically designed as authentic dialogues, where the answers of the NPC’s are made up of short video sequences. On the other hand, the sections where the player virtually enters the innerdiegetic “past” of the game, can be differentiated through their appearance as comic sketches. Consequently, the direct access to the past is stronger connotated with its artificiality, it being something like “in a comic book”. Still from own gameplay.

he game offers a playful space to answer the question “What would I have done?” while always returning to the distanced, yet emotionally highly involved, position of a descendant, a deferred witness. The player experiences her own significance in these memory processes, her very personal contribution to the success of this memory work.

Summarising, I argue that it is precisely this experience of involvement, playful testing of roles and narratives and most especially the very personal contribution of, what at least feel like, self-created outcomes as a “prosthetic witness” that is enabled by digital games. It is this effect that makes them powerful memory media. As equally involved agents of the digital memory sphere, game developers, studios, and the players themselves will influence how the relations between memory and gaming will further develop and what new perspectives will emerge from “played” memories.

Tabea Widmann is a doctoral student at the University of Konstanz, Germany. Her dissertation project „»The Game is the Memory«. A Memory Cultural Analysis of Prosthetic Witnesses of the Holocaust in Digital Games” (working title) focuses on digital games as memory media and concepts of medialized testimony.