Reading Call of Duty: WWII as Digital Holocaust Memory

The heavily anticipated release of Call of Duty: WWII (Sledgehammar Games, 2017) (COD:WWII) was rendered by fans and critics as a ‘gutless view of the Holocaust’ which failed on several fronts. Exploring COD: WWII as a primary case study for her PhD research, guest blogger Kate Marrison considers the positionality of the player in the main military campaign and explores their ability to interact within the digital labour camp.

The campaign follows the story of Daniels (the player), a young United States Army Private and his squad, the United States 1st Infantry Division, during 1944 when the Allied armies were gaining strength and moving into Nazi Germany. During the Battle of the Bulge, Jewish character Zussman is captured and taking to a P.O.W camp where (during a cut-scene) he boards a boxcar destined for Berga labour camp. The game quickly returns to Daniels who is resting in hospital in the Ardennes forest and Zussman is not seen again until the final mission is complete, and the War is ‘as good as won’.

The game uses the historical episode of Bad Orb as temporary camp to align its narrative with the deployment and deportation of Jews to imply a proximity to The Final Solution without explicitly representing concentration and/or extermination camps. Out of the 350 American soldiers forced into the boxcar and sent to Berga (not to be confused with Berg Concentration Camp), only 80 were actually Jewish. Berga was a subcamp of Buchenwald, where it is recorded that prisoners were forced to dig mine shafts into Steinberg (Stone Mountain) on the bank of the Elster River and were slowly worked to death alongside European Holocaust victims (see Bard 1994, Whitlock 2005, and Cohen 2005). Thus, the game ambivalently presents the unknown story of the Berga soldiers within the context of World War Two while implying an interrelation with the persecution of European Jewry. To be sure, the Holocaust iconography (barbed wire, watch towers, barracks) signals to the Holocaust while making incessant disclaimers that the story is about the wider context of War and ‘Americans. Period’.

Fundamentally, then, the game hesitates and only teeters on representing the Holocaust within the short cut-scene mentioned above and a single level (for want of a better word) of the game which is strategically situated in the epilogue. The structural framework suggests the camp is not part of gameplay per se, but that it is something separate to the main campaign – something deferred and of its own significance. My investigation therefore exclusively focuses on the epilogue and more specifically, the space within the (labour) camp, to consider how the player is invited to perform and interact within this setting often considered as a kind of sacred memoryscape.

The Epilogue

As the player enters the camp, the return of the health bar indicates the return to game play. However, what soon becomes apparent is that she has limited agency, she cannot shoot, run or even skip. This is in stark contrast to the final mission which saw the epic battle across The Rhine. Lev Manovich reminds us that the unique pleasure of videogames is derived from overcoming challenges and discovering the rules of the gameworld. As a rule-based experience, he states the player ‘learns its hidden logic – in short, its algorithm’ (2001). Sure enough, the player is presented with numerous challenges throughout the campaign (typically increasing in difficulty), which involve mastering weapons and shooting down enemies to advance across various terrain. However, in COD:WWII, her skillset which is developed throughout the game is suddenly rendered obsolete within the camp setting.

Alexander Galloway’s four categories for gamic action are useful for exploring this decline in game play. Drawing from film theory, he speaks of the diegetic and nondiegetic within the gameworld. Essentially, gameplay is reduced to a series of ‘nondiegetic machine acts’ and ‘nondiegetic operator acts’ (2006). For instance, the player is forced to follow NPCs (non-player characters) Stiles and Pierson as they lead the way through the camp assisted with digital arrows, a proximity meter, and dialogue. The digital arrow and proximity meter are ‘nondiegetic machine acts’. Used in this way, they constitute what Galloway calls an ‘enabling act’, which is where ‘the game machine grants something to the operator’ such as a piece of information. The player uses these prompts to navigate the camp and is forced to pause at the gallows and barracks for reflection. Significantly, then, she is ushered through the camp via the game semantics in a form of organised walking that we often find in traditional Holocaust museums. Moreover, this is the only section of the game that requires the player to control the avatar without needing to use a weapon. While this is not surprising given the FPS (first-person shooter) genre in which the game is situated, it is noteworthy that this is the only mission which requires nothing more than basic move acts, that is the form of player character motion (pushing the analogue stick forward).

Call of Duty: WWII, proximity meter suggests Zussman is amongst the dead

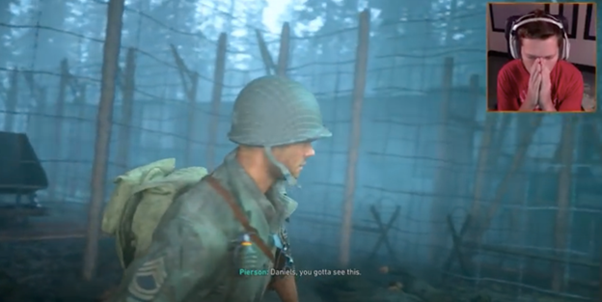

Upon reaching the other side of the camp, the proximity meter which marks their location to Zussman rapidly declines as Pierson discovers a pile of corpses. It reaches 1.4M before disappearing off the screen, which deliberately misleads the player into thinking Zussman is amongst the dead. This is an example of when the ‘the line between what is diegetic and what is nondiegetic becomes indistinct’ as the ‘machine act’ now has narrative value. Researching the reception of the game using online walk-through tutorials proves that experienced players in the gaming community express concern for Zussman at this point. Online gamer, TmarTn2, for example, (who has 4.41 million subscribers) raises his hands to his head and shouts

I thought he was about to say he [Zussman] was one of those bodies.

To the player’s relief, Zussman is not amongst the corpses and Pierson points to the forest to indicate that he has been led on a march out of the camp. Indeed, the Hollywood happy ending ensures Zussman is rescued and the final scene of the game shows the platoon back at base, revealing in victory.

Call of Duty:WWII TmarTn2 puts down his controller and holds his hands to his face assuming Zussman is dead

Advancing Ian Bogost’s theory of procedural rhetoric, I argue that it is precisely the gameplay mechanics which issue symbolic arguments about ways of engaging with Holocaust memory. The processes, structures, and rules of the game communicate to the player that she cannot play within the camp landscape and the rules of engagement have changed. As Bogost proposes, games can issue persuasive arguments through the rules of experience, and in this case, the decline in the possibility space can be physically experienced or felt by the player. Not only does this reinforce the Holocaust gaming taboo, but it also deliberately undermines the player’s expectations that were to play in some capacity. In essence, the game breaks ‘from its supposedly primary role as entertainment software and becomes social commentary’ (Bogost 2006).

As Bogost states:

our experiences construct mental models of the simulation that converge on an interpretation based on what the simulation includes and what it excludes.

The mechanical organisation of the text here breaks with the traditional procedural and structural rules of FPS gameplay prompting the player to question what ideological assumptions are embedded within the underlying model? To be sure, as Bogost argues:

all simulations are subjective representations that communicate ideology.

To reiterate, the camp landscape does not pose a problem to the player and (unlike other levels) there are no trophies or mementoes to be obtained. Instead, it nods to debates around ‘Holocaust etiquette’ and ideas of behaviour and performance within ‘site-specific’ landscapes (Mitschke 2016). This also raises further questions around the player-avatar identity and potentially disrupts their sense of ‘vicarious kinesthesia’ (that is their impression of agency in the digital world) (Darley 2000). Tabea Widmann talks more about player-avatar representation in Holocaust computer games in a recent blog on this site.

In light of these findings, we can return to the reviews which opened this discussion and suggest that it is not only the ambiguous and evasive way in which Holocaust themes are dealt with which disappoints the gaming community but also that the epilogue betrays the language of videogame rhetoric. Players may have (subconsciously) registered the decline in gameplay at the moment in which the designers promised ‘not to shy away’ from the History. While there has been discussion of the epilogue as a kind of digital tour of the camp, it seems to omit the very thing that makes videogames a distinctive mode of engagement – playing. Indeed, it reaffirms the long-standing taboo surrounding Holocaust (video) games and we are left with the impression that one of the most popular franchises of all time falls short of Wulf Kansteiner’s call for ‘simulative and interactive ludic digital environments’ .

Kate Marrison is a PhD researcher at the University of Leeds exploring the preservation of Holocaust memory in digital culture. Her project titled Digital Witness: The Experiential Turn in Holocaust Memory takes an interdisiplinary approach to consider multiple case studies including video games, virtual reality, and interactive testimony. Kate is also a research assistant on the AHRC funded project Virtual Holocaust Memoryscapes.