Spotlight: A Town Called Auschwitz

By Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden

The 27 January 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and Auschwitz-Birkenau. These former Nazi concentration and death camps respectively are two of the most visited historical sites in Europe, yet the Jewish history of the town in which Auschwitz lies is far less known. In this month’s Spotlight, we take a look at the development of the augmented reality app making visible this past.

The Polish town Oświeçim was called ‘Auschwitz’ in German both back in the 15th Century and during the Nazi Occupation. It was also known as ‘Oshpitzin’ in Yiddish. The diverse names given to this town are indicative of its historical multicultural nature.

Whilst modest in size, Oświeçim was well-connected by rail, which helped merchants arrive to sell goods in its central market square. These transport links would of course go on to have a more sinister role under Nazi rule, enabling the mass movement of Jews, Roma and Sinti, and other victims from across Europe to Auschwitz I and later also Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II).

As major commemorations take place at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum to mark the 80th anniversary of the Red Army’s liberation of prisoners this year, more than 1.5 million visitors tour these historical sites and their contemporary memorials each year. Yet, most of these visitors come by train or on an organised coach trip from Kraków; few leave realising that they have come to a Polish town that once had a thriving Jewish majority (circa 60% before the Nazi invasion) but has had no permanent Jewish residents for 25 years.

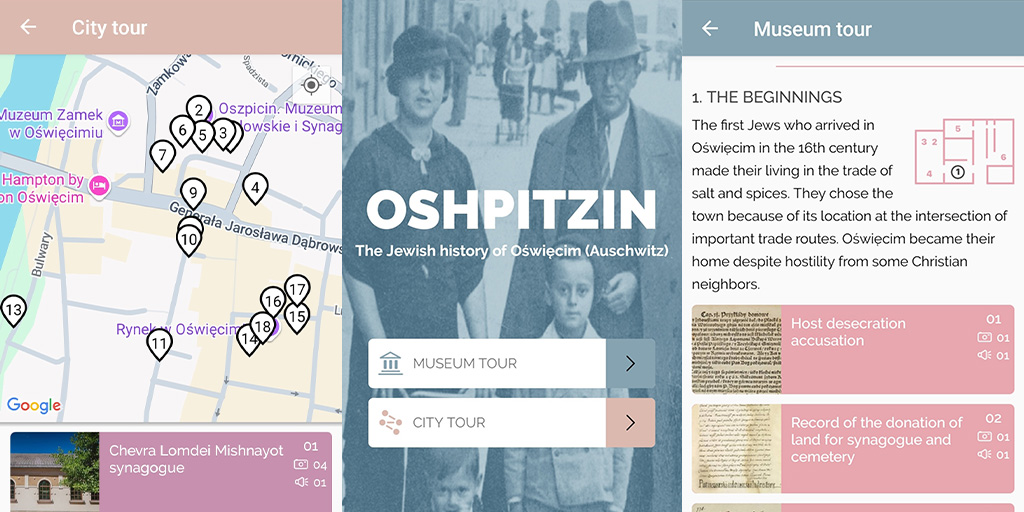

Oshpitzin was one of the first geo-located mobile applications developed for Holocaust education, and it aims to address the knowledge gap above. First released in 2012, it has been a long-term project of the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation (one of our project partners), going through numerous iterations.

The challenge for the team at the Center, led by Maciek Zabierowski on this project, was how to help visitors to Oświeçim have an intellectual and affective engagement with the town’s rich Jewish history in-situ, when there are no Jewish people, and few traces of sites related to Jewish life still standing. At the same time, the team hoad to recognise that ‘the town is still here. Life goes on’, so any experience should not be too invasive to current activities.

Oshpitzin offers two functions:

- It serves as a museum guide, providing further context to objects in the Center’s exhibition spaces.

- It offers a town guide, enabling visitors to learn more about historical sites of Jewish life in Oświeçim.

Homepage of Oshpitzin App

In the original version of the town view, users could roam the streets of Oświeçim following a GPS-enabled designed map (later incorporating Google Maps navigation), which signified different types of buildings relevant to Jewish life. These were coloured-coloured by type, for example one colour for a public building, another for places of prayer, another for private occupancies). At each site, the user could reveal a screen with text and audio descriptions of its history accompanied by a series of historical photographs (and later one contemporary image was added) presenting something of the Jewish presence once here and now lost.

The app encouraged users to search the landscape for where these photographs were once taken, opening up (as I have argued elsewhere) an embodied and intellectual space ‘in between’, which encourages their critical engagement with memory.

The App’s Beginnings

Before the app was developed, the team had created a website presenting these historical sites. This included a semi-3D map using Flash technology, but this was not suitable for mobile devices an Flash is no longer usable. Their next challenge was how to enable visitors to see these sites in-situ.

Working with commercial developers, with no background in Holocaust education, they were clear to articulate their aims: they wanted to help people see things that are not there anymore – to ‘add an additional layer’, not give the atmosphere of the past.

They did not want to create an immersive experience where people might get the sense of travelling back in time or walking in the footsteps of the deceased. It’s important to note that not all of Oświeçim’s Jewish community died in the Holocaust. Alfons and Felicia of the town’s prominent Haberfeld family were at a trade fair in New York when war broke out; some Jewish people tried to settle in the town after the war, but faced discrimination. The town’s last post-war Jewish resident, Symcha Kluger – whose former home is now part of the Auschwitz Jewish Center – was buried here in 2000. The app captures this diversity.

Aesthetics

Some of the original ideas from their first developer included a vintage-style menu, medieval-style documents and an inter-war aesthetic, which was not what the Center’s team wanted. They wanted to be clear that visitors are situated in the contemporary moment and to make visible what is not there now.

Furthermore, they wanted to use branding that represented the Center and thus its work as a memorialisation and educational institution. So they did not continue with these developers. Even so, later collaborators initially fell into the cliché of greyscale but were persuaded away from this. The Center’s team also did not want the app to be sombre – it was after all about pre-war Jewish life.

The actual aesthetics were influenced by an original map from circa 1972 from a memorial book published by survivors, which alongside testimonies from those now living in Israel, included a hand-drawn map by one contributor based on his memories of the 1930s. This map was shared with the designer, who put their own style on it.

3D-Modelling

The initial plan for the app was to recreate onscreen a 1:1 projection of the Great Synagogue on its former site (then just a patch of grass) so that visitors could get a sense of its real size – just how imposing this huge structure was on what otherwise felt like an open clearing.

Details of the Synagogue in the App

The Center had the original plans for the building in their archives, so there was little hesitation. It was big, it was important, and it was to do with Jewish life and now gone – this site was key to the impression they wanted to give visitors. Yet, the developers told them that this was not technologically possible at the time. As a compromise, they introduced a QR code which allowed visitors to view a smaller 3D model but currently it is only accessible from a specific book historically available from the Center.

Besides the Great Synagogue, they curated an experience through which visitors would discover nineteen sites. They wanted to include all the sites that still exist – physically at least; those that still have a specific Jewish presence, such as the town’s Jewish graveyard and the buildings of the Center itself; and then selected a number of sites around the market square, some of which have traces of this Jewish past and others none (such as the Haberfeld Liquor Factory. Although since the app’s release, a Hampton by Hilton hotel has been built on this site which has memorialisations to its past designed into it, developed in consultation with the Center).

Influences

The team were influenced by the few existing international apps at the time. Firstly a General Engine used by their partner institution in New York – the Jewish Heritage Museum. This was a platform that offered a Content Management System (CMS), which could be used to easily develop an app tour and could be published straight to app stores.

Secondly, Anne’s Amsterdam by the Anne Frank Museum – an example of one of digital Holocaust memory’s historical projects now gone forever.

Yet, back in 2012 when the first app was developed, there were few, if any, other examples of mobile apps for Holocaust memory and education.

Funding

The Center’s initial seed funding came from the Dutch-Jewish Humanitarian Fund, who supported the website first, and then the app enthusiastically. Once this initial funding was secured, it was easier for the team to get further funding, which came from the local municipality (for every version), the German and American Consulates in Kraków, and private donors in Israel.

For one iteration, they also received funding from local government (Małopolska), who, like most government funds, had strict rules: the money was available for one year only and the output had to be delivered by the end of those 12 months. This is a funding pattern we have heard repeatedly in interviews and can be restrictive for the iterative nature of digital development.

Development Process

The initial app was developed through a collaborative process. There were two educators, the Center director, and curator leading on it from the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation. This team started by brainstorming what the app could be, what it could achieve, and how to potentially achieve this.

They then took the developers on a tour of the sites throughout the town and shared their resources with them. From here, the user interface was designed straight into the app (wireframes were not really part of design processes back then). The Center team then shared the content, and the developers incorporated it.

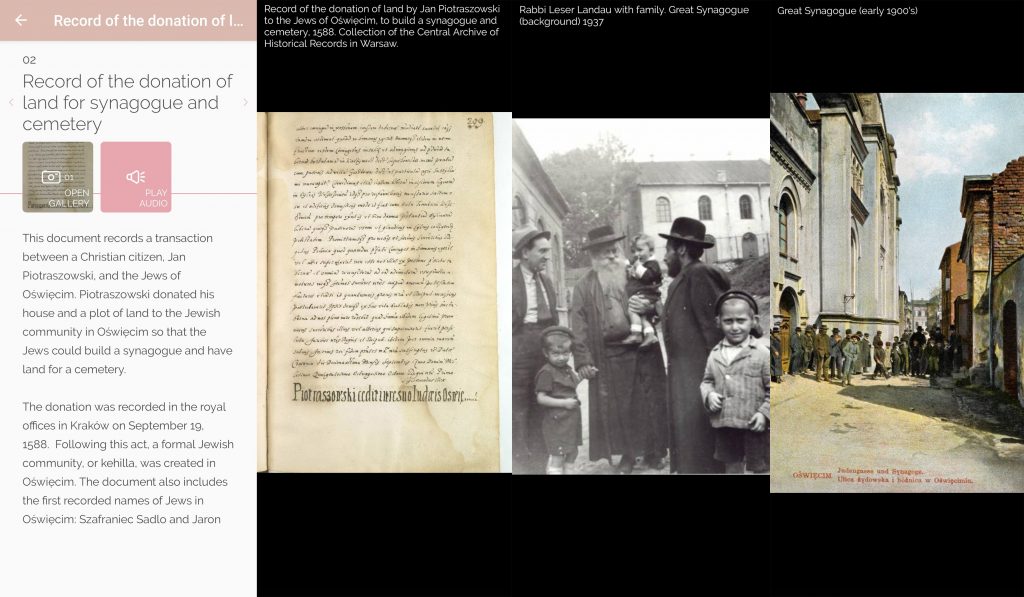

The content was designed to be brief – text that would be readable in-situ (you can’t expect the average user to stand for 15 minutes in busy town streets reading at each site). Images were reliant on what was available, first from the Center’s own collection, then from other major archives in Poland and internationally (such as Yad Vashem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) and some were donated by individuals and families with whom the Center already had relationships. Most of these were already digitised, so there was not too much work to do in preparing them for the app.

During the process, the team did some additional research, primarily sourcing photographs and securing the rights to use them, writing captions, and working on translations.

Then, they scheduled audio recordings in the US, Germany, Israel and Poland, allowing users to access the content in four different languages and offering an alternative to reading at each site.

A beta version was then tested on iPhones with friends and volunteers, and their feedback given to the developers.

In its currently available formats, there is no Content Management System (CMS) through which the Center’s team can easily make updates, so even small changes (including typos) need to go through the developer.

Later Iterations

The app was refreshed circa 2018 alongside visual changes across the museum. Technically, libraries had to be updated and it needed to be developed to keep up with contemporary operating systems.

The new look of the physical Center meant it made sense to refresh the app so they remained complementary to each other. In the museum, bluetooth low-energy sensors were added to make it easier for users to access relevant content. Previously, they had to search for the relevant object and scroll through the app, but now a prompt would automatically open.

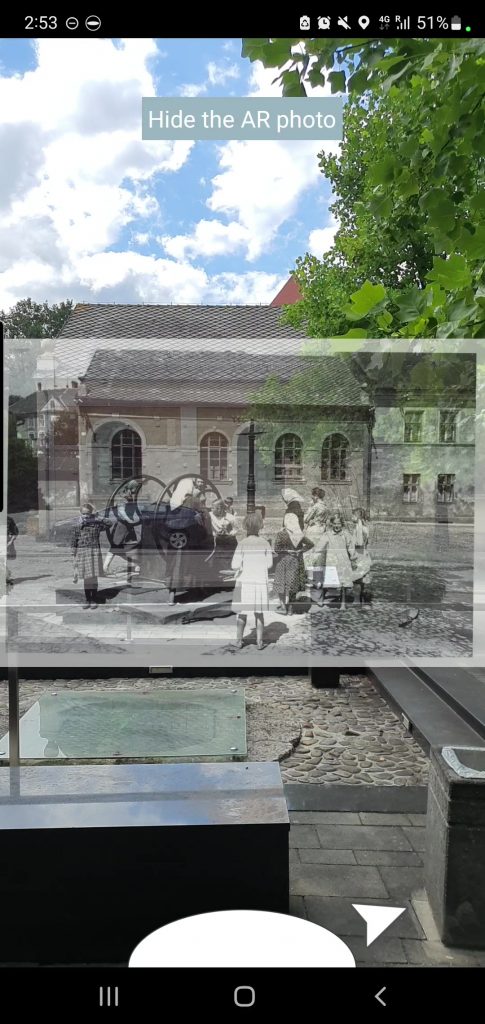

Finally, the team wanted to add Augmented Reality (AR), as the original app only allowed users to view photographs.

Example of AR Function in the App

In this later version, visitors are now prompted to line up the historical photographs which appear to ‘pop up’ in the environment through their mobile screen with today’s contemporary landscape. The introduction of AR into the app means the user is guided towards the correct positioning of the historical images, authentically situating them when previously this had been difficult to do (user feedback had noted this).

However, this guiding gesture means the experience is perhaps less explorative for users as they do not have to do for themselves the labour of searching for how the contemporary landscape and this archival content relate to each other.

Oshpitzin continues to be a long-term project of the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation, and the last iteration ‘A Town Called Auschwitz’ is currently in development.

This Spotlight is based on an interview with Maciek Zabierowski and published with his permission. The interview alongside a walkthrough recording of Oshpitzin will feature in our forthcoming living database-archive. We are proud to have the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation as a project partner of the Landecker Digital Memory Lab.

Want to know more?

Spotlight on Žanis Lipke Memorial

Spotlight on Melbourne Holocaust Museum

Centralising the Human in Digital Humanities Methods