Spotlight: Dachau Memorial

By Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden

The Director of the Landecker Digital Memory Lab reflects on how digitally-mediated experiences of Dachau Memorial rearrange the site’s meaning and affect for her.

On arrival at KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau, most visitors close the gate which reads ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ so they can take a photograph of the infamous slogan. There is no suggestion from the site’s curators or educators that this is a proposed activity at the site – indeed there is no invitation to ‘touch’ historical things (although the gate in-situ is a replica), yet most visitors feel compelled to do this – perhaps due to the iconicity of these three words.

This now ritualistic behaviour is illustrative of the fact that however well ‘curated’ or ‘managed’ memorial sites seem to be, their role as memorial spaces and the meaning and relations relating to the past constructed there rely on the performativity of the multitude of different agents who come to occupy the place – however transiently.

As I walked through the gate the first time during a 5-day research trip to the site, my eyes and thus my whole-bodily attention were draw to two things immediately: the guard tower across the roll call square and the barracks to my left.

Audio tour

However, having received the device for the audio tour from the Information desk, I felt conflicted – deep inside my body – between a desire to cross the roll call square and to explore the historical site on my left or follow the audio tour, which leaves me lingering for an uncomfortable time by the entrance before sending me along the perimeter fence, behind the square into the SS prison – a site I was not quite emotionally prepared for, before sending me back on myself and into the exhibition (for 4 hours).

There, I am overwhelmed with information and constantly looking out for the ‘numbers’ of the audio tour …and soon give up, because there is already so much text surrounding me, I do not feel like I need to listen too.

This level of information is not surprising given Dachau is the most visited Nazi concentration camp in Germany by school groups, so for many – especially young people – it is the place where they learn about the entire Nazi period, the concentration camp system, and the Holocaust (even though Dachau is only really a peripheral site regarding the latter).

The audio tour is very informative – it positions me somewhere between the past and present.

Whilst school kids next to me are fighting with the stones on the ground and I am negotiating the queues in what is very clearly an exhibition space, I am simultaneously aware (thanks to the audio tour) that this has not always been a ‘museum’. It was once the maintenance building of a functioning concentration camp, the architecture of which, I can see (some of) beyond the building’s windows.

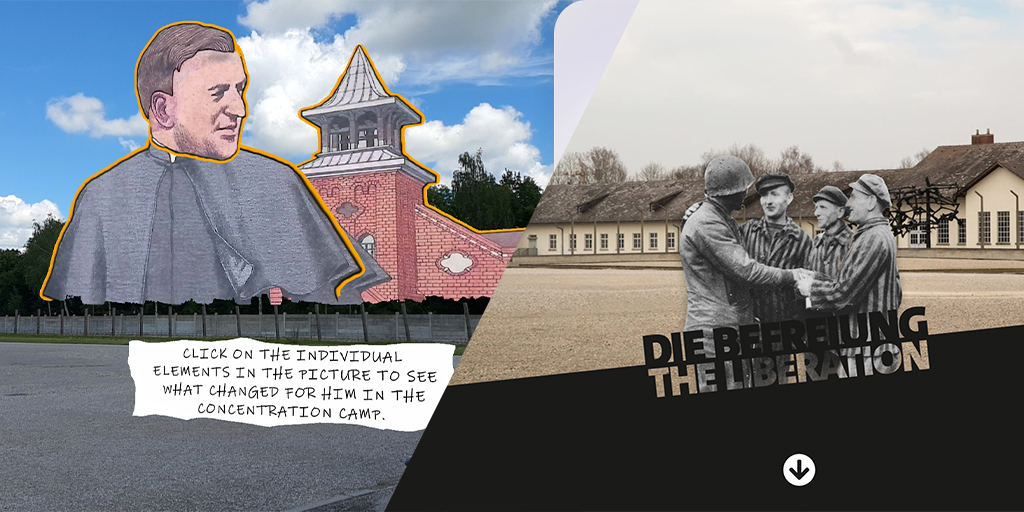

Liberation AR app

Contrary to this experience, is the Liberation AR app – a different device-driven ‘tour’ of the memorial site.

When it was available on-site, it started at the gate, but rather than leading visitors immediately in the historical camp, it sent visitors outwards towards the discarded train famously shot by the photographer Lee Miller.

Use of the AR app was heavily affected by the Covid-19 pandemic because the app was launched for the 75th anniversary of liberation in 2020. The partnership team of the Bavarian broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR), German AR start-up company Zaubar and the memorial site worked together on a web-based version of the app too.

The relationship between site – body – device is once again rearranged here, as space is flattened into images on a computer screen, sound plays automatically but the text must be scrolled. The visitor is no longer ‘at Dachau’ – whatever ‘Dachau’ may be.

The flattening of this experience, which was initially intended to be spatial, reiterates the significance of photographs (as 2D images) to the cultural memory of the Holocaust. Whilst the movement of the audio animates them to some extent, their two-dimensionality on the screen is reminiscent of television documentaries and the large-scale versions of these photographs displayed on entry to the permanent exhibition of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (where Dachau is inscribed as an American memory site).

Here, Dachau is not a space to be experienced, but one that is represented at a distance.

‘The relationship between site – body – device is once again rearranged here, as space is flattened into images on a computer screen, sound plays automatically but the text must be scrolled. The visitor is no longer ‘at Dachau’ – whatever ‘Dachau’ may be.’

A further ‘tour’ of the camp is provided with the ARt augmented reality app – similar in form and produced by the same German startup tech company as the Liberation app, but led by the memorial site rather than journalists (thus without Bayerischer Rundfunk this time).

ARt app

The app situates artworks by victims, survivors and their relatives into locations across the memorial site. Some of the content relies heavily on specific geographic places at the memorial – particularly a dark painting of roll call which appears, once prompted, over the roll call square, and another that presents a comic strip of the registration process for prisoners over a barrack.

The ARt app demonstrates how such mobile experiences constantly involve a negotiation between physical site and digital content, sometimes in (unexpected) ways that distract from the experience, as well as meaningful encounters between the past and present.

The app inscribes a distinct form of testimony onto the site: artwork does not simply tell us what happened, rather its brush or pen strokes reveal the affect of the past on those who lived it (or in some cases, their close relatives). In some cases, the artwork provided far more affect than narrativisation.

For me, this offered both light relief and a more personal, empathic experience with victims compared to the information-heavy exhibition. As artwork appeared to ‘pop up’ in spaces through the memorial site, my attention was at times drawn away from physical structures to digitally-imagined sites of significance – for example, where the digital images appeared.

Unlike the audio tour and the Liberation app, it did not start near the entrance gate, but rather required me to have already crossed the roll call area to find a stand nudging me to download the app. Thus, it required me to already be situated in the memorial site and relied on me having substantial mobile data to access it.

Calibration issues

The app’s digital content was triggered by pointing my mobile device at contemporary stands with the ARt project’s logo on it. To some extent, these disrupted the historical feel of the memorialisation landscape (which of course is always contemporary as it involves substantial upkeep). The stands, however, were a necessary compromise for the memorial site because image-based geo-location proved a challenge at a site where the ground is predominantly grey gravel (thus it is incredibly difficult to differentiate between specific locations).

Unpredictable data connection, however, meant at times I lost calibration frequently and needed to return to the same stand several times adding a repetitive action to my tour of the site not driven by historical curiosity but rather by practical necessity.

At times, calibration issues led to me being directed to position myself on top of the memorial outlines of barracks (and I hesitated, deciding to re-calibrate rather than step here because I assumed these were out of bounds). One time, it led me onto a raised bank with a tree, standing on which led to stepping on an ant hill and an unexpected encounter with the micro-nature of the memorial site which drew my attention immediately into the present!

What did this experience at Dachau teach me?

- the introduction of digital technologies into Holocaust sites, does not essentially change Holocaust memory work, which is usually mediated, and always necessitates movement between past and present

- nevertheless … these technologies play a role in relationality with other agents, so that each digital experience produces a rearrangement of a site

- it is not simply that each platform or technology produces a specific tour, experience, or situates the visitor in a distinct encounter with the site, but rather I would argue that with each distinct experience, the very ontological idea of what is ‘Dachau Memorial’ and also the histories and memories to be understood and felt about the site we call ‘Dachau’ is produced anew. Thus, each rearrangement creates a distinct ‘Dachau’.

This is not an experience distinct to Dachau of course and is something we should reflect on with every mediated encounter with a Holocaust memorial site.

However, it comes to particular attention at Dachau, which even without digital intervention refers to a myriad of actual places: Dachau the historical concentration camp, Dachau the town, Dachau the contemporary memorial site.

What then do we mean when we say, we have visited Dachau?

Want to know more?

Read our recommendation reports:

Guidelines for a more sustainable approach to using virtual and augmented reality

Shaping the Future Use of VR, AR and Computer Games in Holocaust Memory

Read our other Spotlight blogs:

Spotlight: A Town Called Auschwitz