TikTok and Holocaust Memory: Where Commemoration and Algorithmic Culture Collide

by Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden

Our article ‘An Entangled Memoryscape: Holocaust Memory as Social Media’ was recently published in the academic journal Memory, Mind and Media. Here we summarise the key findings.

The article written by myself and my colleague Dr Kate Marrison questions the uncritical acceptance across Holocaust Studies that there has been a paradigmatic shift from the ‘era of the witness’ (Wieviroka 2006) to the ‘era of the user’ (Hogervost 2020).

Instead, it adopts a post-humanist approach, working with the writing of Karen Barad (2007) to argue that social media engagements with the Holocaust should be understood through the lens of entanglement.

What this means is that social media is ‘socio-technical’ (van Dijck 2013) – any ‘agency’ (although we prefer Barad’s word ‘actancy’) involved in its creation involves a multitude of human and non-human actors in an ongoing, iterative process embedded in a variety of social contexts. This includes the corporate platforms, their algorithms and ideologies, the content creators, the platform itself, and the users who comment, like and otherwise interact with shared content.

Furthermore, it means that social media does not just produce Holocaust memory, but that Holocaust memory content on these platforms has the potential to affect not only users, but content creators, and the platforms and their computational and corporate logics too.

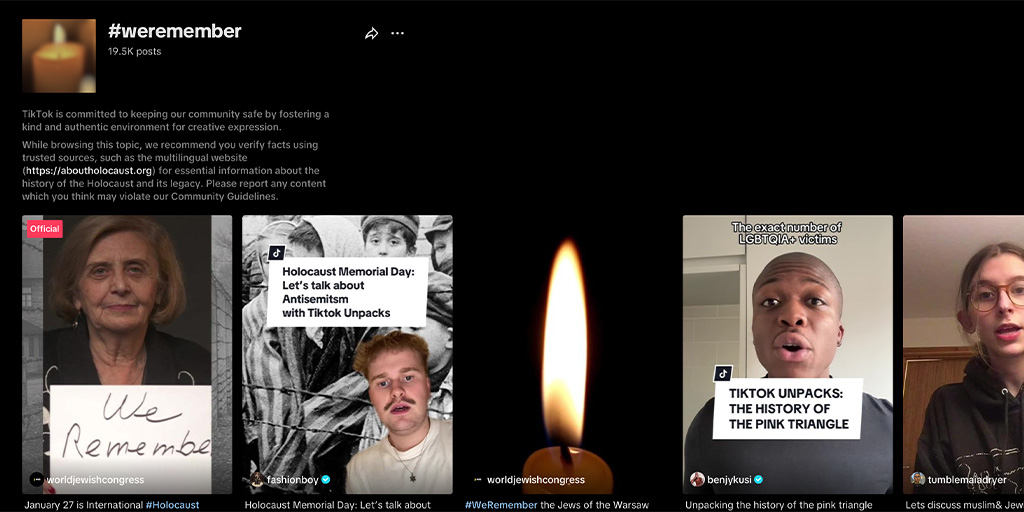

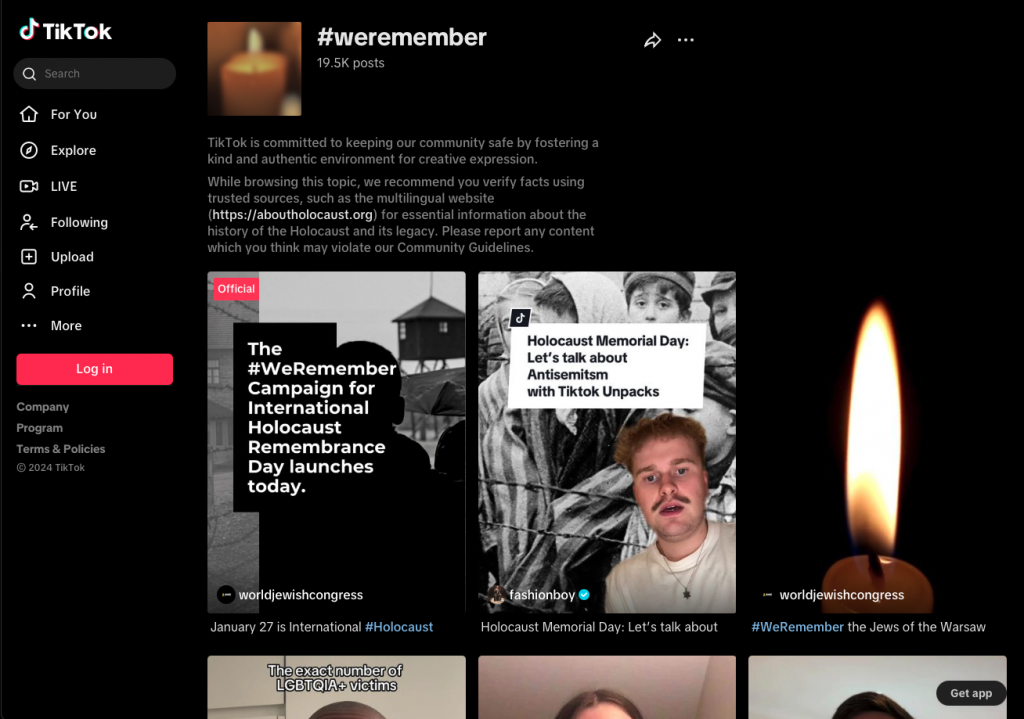

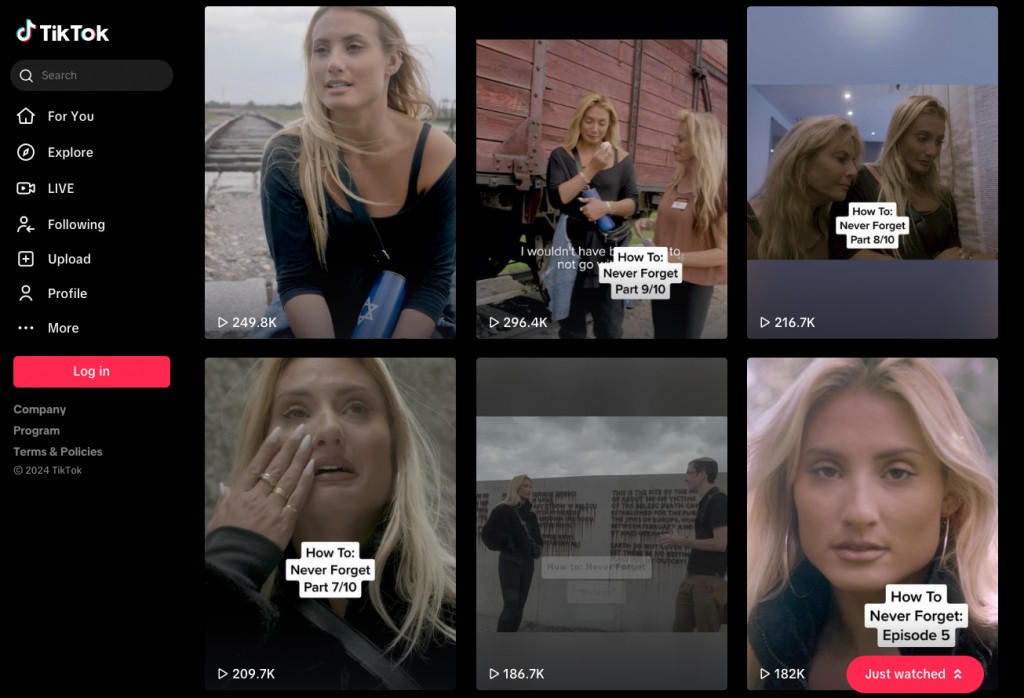

We made our claims through analyses of the #WeRemember campaign (World Jewish Congress and UNESCO) and Montana Tucker’s docuseries How To: Never Forget (funded by the Claims Conference).

We are moving away from traditions of Holocaust representation towards socio-technical performativity.

Five Key Takeaways

- In memory studies more broadly and Holocaust Studies specifically, social media has often been described as demonstrating a ‘bifurcation of memory’ (Hoskins 2014), e.g., a new divide between institutional memory (from above) and public memory (from below). Most writing on this subject has also focused on social media as user-centric and centralising the ‘self’ (see terms like ‘I-witnessing’ [Ebbrecht-Hartmann and Henig 2021]). We argue instead that too much emphasis on the user ignores both the corporate and technical dimensions of social media, and the multitude of interactions between humans and humans, humans and computers, and computers and computers that shape them. Instead, we follow van Dijck in arguing that they are socio-technical ecologies. Holocaust memory is becoming increasingly post-human.

- Through the computational, memory becomes ‘relational data always open to potential connectivity with other data opposed to memory as coherent narratives about the past’ (paraphrased from Hoskins 2014). Thus, users and their data are understood (or better ‘processed’) in completely different ways to how they are presented at the interface. Behind the screen, algorithms perform commands often based on probability modelling and pattern recognition, data is called up from databases based on inputs that are read computationally. Here, we are moving away from traditions of Holocaust representation towards socio-technical performativity.

- Algorithms have always been fundamental to social media, however, TikTok particularly foregrounds them by deprioritising features for human-to-human ‘social’ contact, such as messaging and ‘following’ for the sake of algorithmically curated content via the ‘For You’ thread which appears immediately upon opening the app. Here, then, content seems divorced from context (Bharndari and Bimo 2022).

- We argue that reading Holocaust memory on TikTok in particular, but also social media in general, through the lens of entanglement is productive because it:‘

-

- helps us to acknowledge the complex levels of agency involved in its production

- recognise(s) that the phenomenon comes to define the users, platforms, cultures, and practices involved in it as much as being defined by them

- can lead to the creation of social media campaigns that adopt the specific affordances of Web 2.0 platforms when recognised in the planning process’

- Our two case studies present distinct uses of TikTok: the #WeRemember campaign demonstrates the potential for thinking through entanglement in the planning process – a partnership between the World Jewish Congress and UNESCO, and social media platforms themselves, the campaign was not only prioritised by algorithms due to free sponsorship but also intercepted other user’s posts with an overlay directing those who see any content related to ‘the Holocaust’ to the project partners’ information website. The link reinforces the algorithmic logic of TikTok yet draws users’ attention away from the platform. In contrast, Montana Tucker, who usually engages fully with the wide range of TikTok-specific tools, such as ‘duets’ in much watched dance videos betrays her professional strategy on TikTok by adopting a more traditional style and tone to her Holocaust memory docuseries. Her team respond to long comments from other users about their own connections to Holocaust histories with a simple ‘prayer emoji’ presenting what we call ‘commenting without commenting’ (influenced by Hoskins’s ‘sharing without sharing’ [2018]), in which comments are used to help boost the post’s visibility via the algorithm rather than for social interaction.

In conclusion, we argue that ‘the phenomenon of Holocaust memory on social media is shaped by a complex entanglement of human and non-human actants, wrestling with the tensions between commemoration traditions and algorithmic culture. In both examples, however, it is not only Holocaust memory that is produced, #WeRemember alters the logics of TikTok and writes over user posts whilst the introduction of Holocaust content into Tucker’s account rearranges the coherence of the ‘self’ presented as this social media influencer’s brand identity.

To maintain and grow a significant visibility of Holocaust memory in these online spaces, Holocaust organisations and other creators need to give serious attention to how they work with platforms, algorithms, and expert creators recognising that actancy is dispersed across all.

Nevertheless, this is not an easy task. Social media platforms are notoriously secret about the algorithmic design and regularly alter the computational logics that arrange content both on their sites and in relation with others’.

Read the full article, in our Publications area.

Want to Know More?

Serious TikTok: Can You Learn About the Holocaust in 60 seconds?

More on the #WeRemember Campaign

Read other publications from the Landecker Digital Memory Lab