TikTok #HolocaustChallenge

A few weeks ago on Twitter, I pondered whether there was a place for Holocaust institutions on TikTok, then posts with the hashtag ‘#HolocaustChallenge’ went viral on the platform and hit international headlines.

It has taken me a while to come to write something on this topic. As soon as I took some much needed leave (with no internet signal), of course, a major digital Holocaust memory debate took place.

Context: From Holocaust Denial to Holocaust Distortion

There is increasing and necessary discussion taking place within the Holocaust education sector about not only online Holocaust denial, but Holocaust distortion.

Yehuda Bauer, Honorary Chairman of the IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance) has recently argued in a series of keynote lectures that Holocaust distortion is one of the greatest threats to the work of those who are trying to educate about this past. We see examples of distortion at political levels – such as the controversial ‘Holocaust Law’ in Poland, which tries to prevent acknowledgement that some Polish individuals and communities were antisemitic and/or were responsible for the murder of Jewish individuals during Nazi Occupation of Polish land. We also see examples of distortion through trivialisation of the Holocaust into commercial products such as face masks displaying concentration camp iconography apparently to ‘help us remember this past’ (these tasteless items were removed from Amazon’s site after much campaigning).

Young People, Social Media and Holocaust Memory

Nevertheless, there have also been many often well-intended, but condemned, attempts by young people to present an engagement with the Holocaust via social media. The most well-known of these previously was the selfie shared by Breanna Michelle, in which she was seen ‘smiling’ at the Auschwitz State Museum in a ‘selfie’. This caused so much outrage that Breanna received death threats and was forced to remove her Twitter account.

(RNS1-JULY 24) On June 20, Breanna Mitchell posted a selfie on the grounds of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. For use with RNS-AUSCHWITZ-SELFIE transmitted July 24, 2014. Photo courtesy Breanna Mitchell

The selfie storm continued as more images of teenagers – mostly girls – posing at memory sites circulated around social media sites, particularly on the image-laden Instagram. German-Israeli comedian Shahak Shapira created the website Yolocaust, which superimposed these young people’s images over atrocity photographs when the user hovered their mouse over them. It was an attempt to shame the image-makers – a tough love form of Holocaust education. It worked – every one of them got in touch to ask for their images to be removed and apologised for their apparent mistakes.

Shapira, however, had focused on images taken at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews in Europe, which architect Peter Eisenman wanted to fuse into the everyday landscape of the German capital. He has repeated several times that he did not want this to be seen as a sacred site, and his thinking echoes the philosophy of Giorgio Agamben, who argues that we need to understand the everydayness of Auschwitz, rather than side-line it as so exceptional that it is beyond human experience. If we accept its everydayness, then we can begin to think about how we might stop something like this emerging from within our societies in the future.

The individuals, whom Shapira superimposes over atrocity images were not literally ‘dancing’ or ‘juggling’ on people’s graves. The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is well-known for being a site with little historical relevant to the mass murder of European Jewry.

More recently, the Auschwitz State Museum received criticism from academics – mostly female – after the Museum’s twitter account shamed young girls for taking sexually suggestive images at the site. Both the Museum and Shapira did not contemplate the aesthetic form of the selfie and that the poses of the young people on show might be

- conventional to the format, just like the cue ‘cheese’ makes us smile on command when someone else takes a photograph of us

- a sign of the pressures that young girls particularly, but also teenage boys, face in constantly presenting perfect images of their bodies online.

Shaming these young people, who, after all, had made the effort to visit a Holocaust memory site, and their selfie(s) were only a very brief ‘snapshot’ of a longer educational experience, seems unproductive and unethical in the context of Holocaust education and Holocaust memory.

Firstly, if we shame them, we may exclude them and thus put them off engaging further in this topic for fear they might offend (again). The Holocaust, then, becomes ‘out of bounds’ in their discourse. Secondly, if Holocaust education sits in a wider sector of human rights learning, public humiliation and bullying, which sometimes lead to the incitement of death threats towards young people seem grossly counter to our agenda.

Is what they are doing to be equated with the trivial commercialism of Holocaust face masks or the seriousness of Poland’s ‘Holocaust Law’, or should we more carefully consider their intent, their learning experience, and the effect the circulation of their images might have on encouraging other young people to visit these sites? Are their images distortion or rather a new aesthetic form that more mature Holocaust educators do not understand?

Where does the TikTok #Holocaust Challenge sit amongst this?

What is TikTok?

TikTok was launched in 2017 by the Chinese internet technology company ByteDance. It is a video-sharing social networking service, originally used to create short music, lip-synch, dance, comedy and talent videos. The videos play on loop and are usually 3 to 15 seconds. It only became available beyond China in the summer of 2018, but has become more well-known internationally during the Covid-19 Pandemic of 2020 and the attempt of US President Donald Trump to ban the platform in the US.

Alongside the circulation of memes, a popular format on TikTok is the #POV post, which is both an extension of and a flip of the selfie format. In #POV videos, the camera offers a first-person perspective so that protagonist is supposed to be the viewer, to whom the tightly-framed creator speaks. It is a particularly effective format on TikTok because users are greated with an algorithmically-generated ‘For You’ page on which videos play to them automatically. #POV videos are intended to entangle the user into their narrative, making them responsible for their response to the dialogue started by the creator.

‘Challenges’ have become trending hashtags on the platform and are intended to get users to be part of a wider community by participating in a shared action, from the physical transformation #dontjudgemechallenge to the active, dexterity #bottlecapchallenge. Similar modes of participation, sharing and circulation have featured on Instagram and Facebook, including the #nomakeup selfie and #waterbucketchallenge, both controversial at the time, but used to raise awareness and funds for charities. The platform has also developed partnerships with edtech companies using the hashtag #EduTok. Nevertheless, it is still dominated by user-generated content (much like YouTube in its early days). Whilst some museums, notably the Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam have enthusiastically engaged with TikTok, it is still underexplored by much of the education, museum and memory sectors.

What is the #HolocaustChallenge?

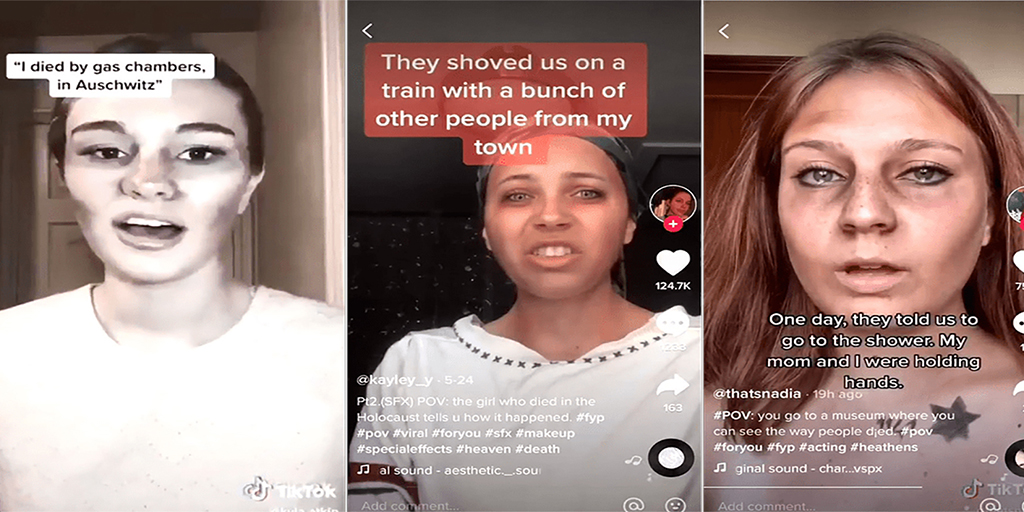

#HolocaustChallenge was one of a number of TikTok challenges encouraging users to create #POV videos. Those highlighted for criticism share a similar narrative and aesthetic:

- A young person in 2020 appears on screen

- A sudden cut then transforms them into a Holocaust victim in #heaven, or back in the past, just before they are deported and/or murdered

- Text appears on screen describing a fragment of their story, and often how they died, as the teen performer appears to look like a ghost – their makeup supposed to represent how they died (as is typical of a wider trend of these #heaven #POV shots). They often wear clothing appropriate to their ‘character’ when they died, i.e. a yellow star or the striped concentration camp uniforms commonly, although problematically, referred to as ‘striped pyjamas’

- Their brief 15 second or so videos are directly addressed at the viewer telling a short snippet of a possible way in which Jewish victims were persecuted and/or murdered by the Nazis and their allies, they are presented as if they ask for a response from the viewer

- Many of these play to soft or popular music (a key feature of the multimedia format of TikTok videos), such as Bruno Mars’s hit ‘locked out of heaven’

- The video loops back to the beginning.

- Some videos use simple greenscreen effects to show the costumed actor (or more appropriately, usually an actress) against a photographic background of a site such as Auschwitz or a major European city, before their character is deported.

The Debate

These videos were quickly lambasted in the press, and the Auschwitz State Museum released the following on

The ‘victims’ trend of TikTok can be hurtful & offensive. Some videos are dangerously close or already beyond the border of trivialization of history.

But we should discuss this not to shame & attack young people whose motivation seem very diverse. It’s an educational challenge. pic.twitter.com/UC7lM6gudj

— Auschwitz Memorial (@AuschwitzMuseum) August 31, 2020

This carefully worded tweet from the Museum suggests some learning on their part regarding the consequences of international news outlets circulating stories about young people’s Holocaust projects online. They now condemn any shaming or attacks on the creators of these social media videos, calling it an ‘educational challenge’, which one assumes needs to be solved rather than acting as, as some have called them, ‘the Holocaust Police’.

In the press, the videos were described by a number of outlets and commenters as ‘cosplay’, ‘trauma porn’, ‘imitating Holocaust victims’, ‘dressing up’ or ‘role playing’, ‘pretending’, ‘outrageous’, ‘disturbing’, ‘antisemitism’, and the creators accused of jumping on the Holocaust trend for the sake of ‘fame’.

Some creators described their motives to Wired Magazine as follows:

McKayla, 15, from Florida, says she made her video to “spread awareness” of the Holocaust, and to share her ancestor’s story with the genocide.

I’m very motivated and captivated by the Holocaust and the history of World War II,” she says. “I have ancestors who were in concentration camps, and have actually met a few survivors from Auschwitz camp. I wanted to spread awareness and share out to everyone the reality behind the camps by sharing my Jewish grandmother’s story.

Other TikTok users argue that only those with Jewish heritage should create such videos and are wary of how the complexity of this past can be told in a 15 second clip. Holocaust memory is important to Jewish communities, yet, if only those of the same heritage as this victim group remember it then we are not working towards the idea of ‘never again’, i.e. trying to prevent future genocides by encouraging mass remembrance of such atrocities. If only the victim group remember the victims, what does society learn about preventing perpetration?

As a complex history (or web of histories), the Holocaust can never be ‘told’ as a complete, easily understood narrative about the past. If we judge any format on its inability to tackle this complexity, then every museum, site, book, film, testimony and archive is doomed to fail. Fragmentary approaches may have their uses, and we should also be careful to differentiate between history and memory.

If history is the narratives told about the past, then memory is the affective experience of engaging with it. Memory gives us the impulse to continue to commemorate as we feel bodily and emotional engaged with the Holocaust. History teaches us what actually was the Holocaust. They work in a symbiotic relationship, but memory ‘texts’ do not always have to do the work of history, and vice versa.

If young people, despite the stress of a pandemic, feel the urge to represent Holocaust victims and to take the time and effort to create and circulate this representation, surely there is some memory work going on.

Academics have already begun to write about this controversial case study too. On one hand, Professor Sara Jones, an expert in Holocaust testimony in culture, argues that the TikTok #POV videos should not be banned as a format, but they fail as forms of Holocaust education because they do not engage with an ethics of the other, instead favouring a form of empathetic engagement more akin to walking in the shoes of Holocaust victims, or ‘imitating’ their experiences. I have previously discussed some of my own concerns with empathy in Holocaust education. Nevertheless, this raises a pertinent issue – do these videos have to be educational tools or can they just be fragments of (deferred) memory? (creative responses to witnessing or knowledge.)

On the other hand, I am in agreement with Dr Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann and Tom Divon that we must understand these videos in their specific context and appreciate the commitment that these young people show to remembering the Holocaust, even if this is for varying motives. They note that many of the users added the hashtag #fyp (“for you, partner”/ “for your page”), explicitly encouraging other users to create and circulate their own videos.

The #Holocaustchallenge is perhaps one of the first examples of a truly user-generated, viral Holocaust memory. They warn that by lambasting these young people, pressurising them to remove material or hiding the #Holocaustchallenge search (as TikTok decided to do), we exclude the Holocaust as a subject from the TikTok domain – it becomes out of bounds, and possibly then out of minds.

Dr Carmelle Stephens, previously one of our guests at a digital Holocaust memory webinar alongside Dr Ebbrecht-Hartmann, notes an important point in her conclusion to her careful critique of the #Holocaustchallenge videos:

The fact that #holocaustchallenge emerged from the TikTok POV genre affirms the position of the Holocaust as a relevant presence in the cultural consciousness of social media savvy teens. The interest is there, it’s a concept that captures them. This scandal has been a catalyst for suggestions of tighter controls on social media. This is the worst thing to do. If you don’t like what young people are doing with this topic, talk to them, don’t tell them to shut up. You can’t say ‘don’t touch that, that isn’t yours.’ Before long it will be theirs, and what we do now will determine what they do with it. The idea that the Holocaust has a magical exemption from comparison, debate, recontextualization and creative interpretation is guaranteed to create just enough resentment to condemn it to an irrelevant historical footnote before too long.

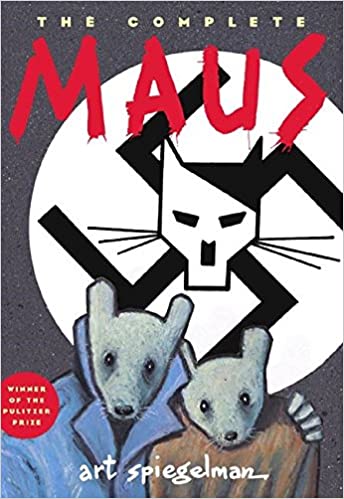

Dr Stephens’s points are reminiscent of conversation that we were having decades ago about Holocaust representation in popular television, film and in graphic novel film (remember Maus). Texts that were once controversial, like Holocaust, Schindler’s List and Maus, are now canonical in any university course about Holocaust representation. If digital media is so-called ‘new media’, then we should be concerning on its specifics and what they might do for Holocaust memory, rather than simply repeating the same old criticisms which have been directed to each ‘new media’ that stakes a claim in Holocaust representation.

There is an increasing amount of explicit Holocaust denial and distortion online and offline, and there have been claims that TikTok is suppressing content by people with disabilities and related to the treatment of Uyghur people in China; the international debate that has sparked about these TikTok videos feels like a distraction from these more pressing concerns.

#HolocaustChallenge as Holocaust Fiction

Some of the language used in the popular press to describe these videos seems to go out of its way to avoid talking about these #povs as ‘representations’, ‘fiction’ or ‘performance’. Favouring instead, language such as ‘pretending’, ‘imitating’, ‘fake’ and ‘cosplay’, which all dismiss the videos as amateur and play.

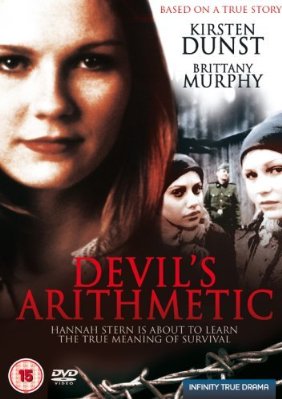

Their conventional ‘flashback’ style reminds me of the US film The Devil’s Arithmetic (1999), in which contemporary teenager Hannah, played by Kirsten Dunst, is almost late for her family Sedar because she is getting a tattoo. As she opens the front door to let in the prophet Elijah, she finds herself suddenly transported back in time to Nazi-occupied Poland. Once in the gas chamber, unlike her fellow victims, she suddenly awakens in her 20th Century family home. Presumably having learned some lessons about the past, she no longer feels like an alienated teenager but part of her family. The film was designed to teach young people about the Holocaust and was based on a successful novel. There are numerous teaching units and resources available online, created by teachers associated with the novel and the film.

The melodramatic music and facial expressions of the TikTok videos can be traced back to so-called ‘silent cinema’ (which was rarely entirely silent), is also a familiar trope of Holocaust films, from Sophie’s Choice (1982) to Schindler’s List (1993), and NBC’s Holocaust (1878). Indeed, perhaps one of the most famous criticisms of popular media representations of the Holocaust was Elie Wiesel’s New York Times article (1989) in which he condemned the latter for its melodramatic and trivialising style. Yet, Holocaust fiction – particularly in the form of feature films – has done enormous work in drawing people’s attention to this past, and making them feel something about it.

Furthermore, the claims that teenage users are jumping on the Holocaust bandwagon to attract fame is reminiscent of the Ricky Gervais and Kate Winslet joke in Extras that to secure an Oscar, she needs to do a Holocaust film (which Winslet then went on to do with The Reader (2008). 19 films about the Holocaust have won Academy Awards, some winning several. The joke is not unfounded, yet Holocaust fiction has done much for Holocaust awareness.

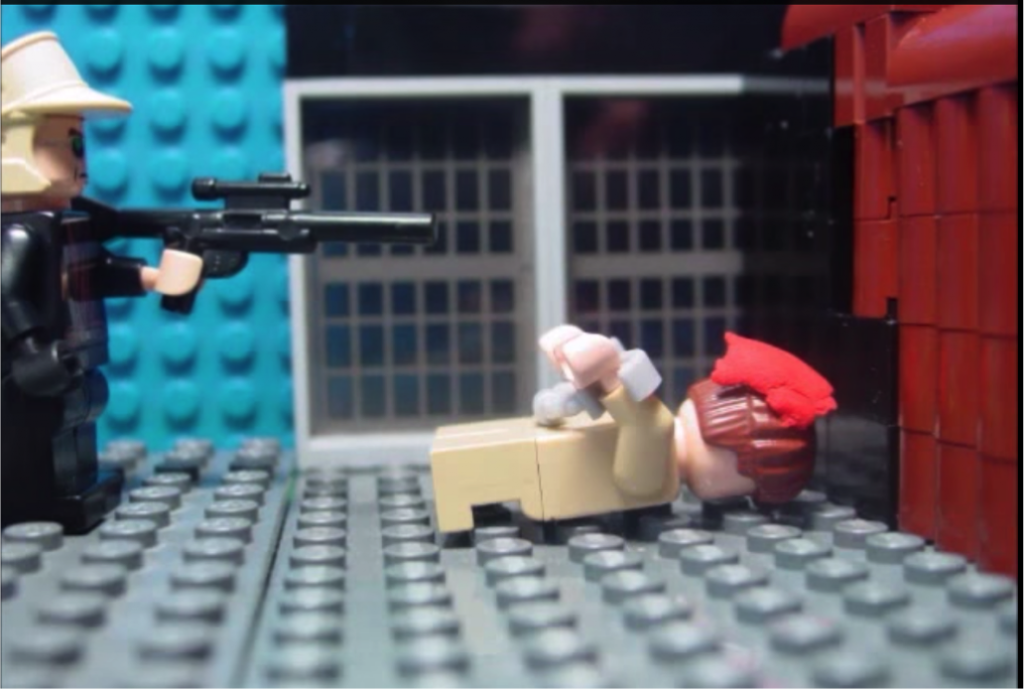

The Need for a Networked Approach to Holocaust Memory

In an article about Lego Holocaust films on YouTube, I argued that perhaps our existing frameworks for thinking about the ethics of Holocaust memory were outdated – that maybe, we needed to look at what young people were producing about the Holocaust, and talk to them about how they perceive it, why they think it is important to remember, and how they feel it should be remembered. This is not to say we should entirely relinquish responsibility of this complex history to the young generation, but rather that we need to open up dialogue with them – particularly those who are dedicating their time to creative ventures such as Lego animations and #POV videos.

James Young (2000) predicted, some time ago now, that the Holocaust was moving beyond ‘living memory’ and towards ‘mediated memory’. It might perhaps be best now to nuance this to say that it is moving towards ‘digital memory’ or event ‘viral memory’ specifically. In digital communication, particularly via social media platforms, representation as understood in both mimetic and meaning-making ways is no longer the primary essence, rather shareability, circulation, and networks in which individuals can participate in what feel like communities have become the central aspects of communicative experience.

Rather than continue a didactic response of ‘this is how the Holocaust should/will/must be represented’, a more networked approach to digital Holocaust memory for the future would open up dialogue with young creatives who are trying to use their talent to navigate the complexities of the Holocaust in which we do not simply tell them what we think they’ve done wrong, but we partake in knowledge exchange. We can learn much from these young creatives about virality and shareability, about the conventions of social media productions, and engaging with their peers. In exchange, we can teach them to critically engage with the Holocaust.

We must remember, it is these young creatives that are producing Holocaust content that is going viral and being picked up by the international press. How often do social media posts by Holocaust institutions have the same effect?